Abstract

The restored Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints includes a priesthood training program for young men, teaching them line upon line as they increase in experience. However, the Church has struggled to provide a complementary preparation to empower young women in their own specialized sphere, without which a full restoration of truth is incomplete. Through a re-examination of the scriptures from a feminine perspective, divinely constructed patterns pertaining to womanhood come into focus. As was taught to Eve at the threshold of mortality, menstruation is fundamental to the eternal calling of womanhood. The symbolism of the blood of the womb echoes in the ordinances of salvation, temples ancient and modern, and the Atonement of Jesus Christ. As we rediscover sacred feminine truths that have been neglected through the ages, we develop a clearer understanding of women and their distinctive purpose in the exaltation of mankind. This perspective can be instrumental to the ongoing development of an educational program for young women, specifically engineered for their unique opportunities and challenges.

Introduction

The Restored Ggospel of Jesus Christ is a living creed, advancing from generation to generation and expanding from continent to continent. From the days of the prophet Joseph Smith, its glorious doctrines have continued to dispel falsehood, promote brotherhood and spread peace throughout the world. Many of the teachings that distinguish the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from traditional Christianity and other world religions relate directly to our doctrine of womanhood.

While many religions view the choice Eve made in the Garden of Eden as reprehensible and hold her responsible for mortal pain, sin and death, the Church of Jesus Christ embraces her choice not only as honorable but as essential to the Plan of Salvation authored by God. [1] While many believe that infants naturally carry the curse of mortality and must be cleansed in order to be saved, the Church of Jesus Christ advocates for the innocence and purity of children (Moroni 8:8). While many faith communities are built, to one degree or another, upon the premise that women are fundamentally subservient to men, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints maintains that women and men enjoy equal and complementary roles. [2]

This perspective towards women, unique in Christianity, positions the Church to embrace a fuller understanding of the eternal destiny of women and their crucial role in the Plan of Salvation.

As our modern societies evolve, young people are becoming enabled to participate in their own agency more than ever before. Individual choices regarding education, career, sexuality, marriage, and children have never been so diverse or accessible. In order to arm our daughters and sons with the wisdom they need to navigate these choices, a re-examination of our canon is necessary. Within our scriptures and the words of our prophets are pearls of knowledge that can help us better understand the pivotal role of women in guiding the human family toward exaltation. [3]

Recently, modern prophets have emphasized that the blessings of the holy priesthood are available to the entire human family through obedience to covenants made rather than through priesthood ordination. [4] With this perspective in mind, the teachings of the holy scriptures can be seen in a new light. Those passages which previously appeared to apply only to ordained men can be re-examined in reference to women and their unique role. Reconciling these scriptural passages with our new insight gives us a broader perspective into the great work our Heavenly Parents have called their daughters to do.

This focus on the doctrine of the role of women may feel uncomfortable or disorienting at first. For instance, you may feel some discomfort or resistance to words such as “priestess.” As a faith community, many have traditionally shied away from using sacred words that apply specifically to women in our congregations. The word “priestess” is absent from the standard works. In contrast, the word “priest” occurs over a thousand times in the scriptures and young men are referred to as “Priests” for two years. We might consider that this reluctance to use words of empowerment in the feminine form stems not from our doctrine, but from our cultural foundation in the Christianity of the apostasy. Misunderstandings about Eve and the role of women abound in the fallen gospel of the apostasy, and many essential topics have been rendered taboo. [5]

Merriam-Webster defines “priestess” as 1. A woman authorized to perform the sacred rites of a religion and 2. A woman regarded as a leader. [6] Surely these definitions apply to the faithful, covenant-keeping women of the Church of Jesus Christ. These women are leaders in local and general capacities, are authorized to perform ordinances in holy temples, and are wearers of the garment of the holy priesthood. There is perhaps no group of women more qualified to be referred to as “priestesses.” We would do well to consider how we might familiarize ourselves with this and other honorable language in the feminine form.

If embracing this sacred feminine language feels like a stretch, imagine how disorienting it might be for a young woman to hear the word “priestess” during her first initiatory experience in the temple. Without previous instruction connecting this word to herself before, or hearing it in any legitimate religious context whatsoever, it would be very difficult to suddenly understand and internalize the blessings and responsibilities inherent in that title. In order to help our young women understand their divine destiny, it is essential for us to continue to broaden and deepen our understanding of the divine role of women.

In Church buildings worldwide, young women stand together and declare, “I am a beloved daughter of heavenly parents, with a divine nature and eternal destiny.” Until revisions were made in October of 2019, the theme acknowledged only “Heavenly Father” as the divine parent. [7] In recent years, similar language adjustments that more fully embrace sacred femininity have poured out in our congregations, general conference addresses, and temples. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is more openly publishing the doctrine of divine progression for women. No longer are these teachings relegated to an obscure line in a hymn or an implication. They are being taught directly, publicly, and consistently by the prophets.

In his wisdom, Jesus Christ established a preparatory Aaronic Priesthood centuries ago to lead his sons toward a higher priesthood. This preparation provides a doctrinal foundation, authority, and sacred responsibilities that guide young men as they mature in the gospel. However, these foundations are largely absent from the young women’s program. Young women currently lack the titles and sacred congregational responsibilities of their male counterparts, and this empowerment vacuum may prove an impediment to the development of young women. [8] Notwithstanding this imbalance, we may consider a deeper understanding of truths that are available as we nurture and guide them. As we teach a purer doctrine of womanhood in our congregations and homes, we will better prepare our young women and enable them to embrace their own highest callings.

The Lord Instructs Eve and Adam

A fuller understanding of the overarching mission of women begins at the very beginning of mortality. Eve had listened to the persuasions of the serpent, weighed his half-truths against her own insights, and made the choice to eat of the fruit. Her decision to consume the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil initiated the Fall. Eve became the very first mortal on this earth when mortal blood coursed through her veins. [9] Eve shared her wisdom and the fruit with Adam, and he also chose to partake.

Their decisions necessitated a change of venue. No longer would they enjoy the bounty of the Garden of Eden and the privilege of closeness with God. Instead, they would enter the testing ground of a new, fallen world, fraught with physical and spiritual perils. As preparation for this new experience, the Lord God instructed first his daughter and then his son, explaining the trials they would encounter in mortality. The following are his words to Eve:

I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee. (Genesis 3:16)

Let’s focus on the Hebrew meanings of some of these words in order to get a clearer picture of what God was communicating to his daughter. The root of both the words “greatly” and “multiply” is rabah (רבה). Elsewhere in the Bible, rabah indicates “multitude, abundance, greatness, myriad.” [10] This is the same root word used when God issued the first commandment to Adam and Eve to be fruitful and multiply. These synonyms point to a repetition of sorrow rather than a prolonged punishment. The word “sorrow’” is etsev (עצב), which can be translated as “hurt, pain or grieve.” [11]

The word translated in this passage as “rule” is pronounced mashal (משל). It is used many times in scripture to designate the relationship of a ruler to his subjects. However, a second meaning for this word, a verb of the same spelling, means “to represent, be like, imitate.” A related noun communicates “poetic parallelism.” [12] Rather than instituting a hierarchical structure for his daughter and son, the Father may have been emphasizing their similarities. A more accurate translation of his words might reflect the parallelism of the genders, especially considering that the subsequent verses are directed to Adam and describe the sorrow he would face in a fallen world. In light of these Hebrew origins, this translation might ring more true:

I will repeat abundantly thy pain and thy conception. In pain thou shalt bring forth children, and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall be like unto thee.

In ancient writings, the order of items in a list is often intentional. Here the Lord teaches Eve about repeated 1) pain, 2) conception, and 3) pain in bringing forth children. From my experience as a daughter of Eve, this description indicates the cycle of menstruation, conception, and childbirth. These three conditions have been an inextricable part of womanhood since the very beginning of mortality. As the Mother of All Living, Eve would pioneer the painful cycle of menstruation, conception, and birth. She would have no earthly mentor or midwife to help her understand these womanly sorrows. Surely the insights she received from heavenly sources would have given her strength as she first experienced menstruation, then conception, and finally labor.

As we examine the role of women in the gospel of Jesus Christ, this instruction from Eden is crucial. The cycle of menstruation, conception and labor is foundational to the doctrine of womanhood. These feminine phases are also some of the most denigrated and misunderstood natural processes on the planet.

Menstruation

Menstruation is a monthly physical condition in which healthy, fertile women regularly release the lining of their wombs. On average, women experience menses from the age of 12 until the age of 50. Menstruation is often accompanied by pain and hormonal upheaval, and women can expect to lose 30-90 ml of fluid during each cycle. In modern societies, the average young woman will experience menstruation over 400 times during the course of her life. Aside from primates and a handful of other mammals, menstruation is unique to humans. Other animals that bear live young simply reabsorb the womb lining internally. [13]

In Old Testament language, menstruation is referred to as “the manner of women,” “the custom of women,” “the fountain of her blood,” and “being sick of her flowers.” [14] According to Mosaic Law, a woman’s menstrual flow is categorized as an issue of blood, indicating uncleanness. For hygienic reasons, the law required women to live outside the camp of Israel during menstruation and to cleanse before returning to their families (Leviticus 15:19). Whether this law was active during the days of Moses or was added sometime later, menstrual law carried major implications for women.

In many traditional Middle Eastern societies, the onset of menses indicates that a girl is fully mature and eligible to be given by her father in marriage. The fathers of the groom and bride negotiate a bride price. In exchange for this dowry, the girl is taken and incorporated into her husband’s household. In many traditions the entrance into adulthood for young men is marked by elaborate rites of passage; for young girls, this entrance occurs naturally through menstruation.

Menstruation indicated a significant deviation from daily activities for the women and girls living under Mosaic Law. Family life, work, education and relationships were dictated by this monthly cycle. Whether these women spent their menstrual days in tents, huts, or other dedicated spaces, their bodies and everything they touched was considered unclean for several days each month (Leviticus 15:19-23). These private practices influenced women’s integration into society and major stigmas around women and impurity developed.

In our modern day, science has caught up with the Mosaic Law. Biology helps us understand hygiene on a molecular level, and it makes sense that cleansing bodily fluids is a good community standard. However, for the ancient Israelites, defining the difference between hygienic uncleanliness and moral uncleanness was difficult. Many cultures determined that menstruation was not only messy, but that it also represented a fundamental sinfulness in women. [15] To quote from the Book of Job, “What is man, that he should be clean? And he which is born of a woman, that he should be righteous?” (Job 15:14).

In order to become clean and re-enter society, the law requires that women be cleansed ceremonially. To this day, thousands of Jewish women practice ritual immersion in a mikveh (מקוה) following their monthly cycles before they can reintegrate with society and be intimate with their husbands. The mikveh of the modern day looks something like a baptismal font. It has other purifying uses, including cleansing those who have been in contact with disease or death. Menstrual cleansing is described by modern Judaism as a spiritual immersion following the death and release of potential life. The mikveh is of such importance to Jewish family life that in many new communities, the building of a mikveh takes precedence above the building of a synagogue. [16]

One can detect in this ritual cleansing echoes of the ancient baptismal rite. Baptism was taught to Adam and Moses but lost its significance, so much so that baptism set John the Baptist apart from other teachers of Judaism (Moses 6:64-66, D&C 84:25-27). Baptism, an ordinance that is required for all as a spiritual cleansing, had become misunderstood. It became a mere physical cleansing, losing its eternal significance and debasing women along with it.

The Hebrew root word used to indicate Jewish menstrual law is nadad (נדד), which has been defined as “retreat, flee, depart.”[17] And retreat these women have, with each cycle, for centuries. The related verb nadah (נדה) is even more aggressive: “to put away, exclude, excommunicate.” However, a second definition of this verb is intriguing.

A more obscure definition of nadah means “to be moist, betide, befall, rain dew, bounty, liberality, a gift.” [18] Consider the possibility of menstruation as moisture, a tide, a fall, dew raining down, bountiful, liberal, a gift. Surely this essential function of a woman’s body, which was created after the image of the mother goddess, is a thing of glory and bounty. [19] The feminine flow, an integral piece of fertility and the ability to bring forth children, is like rain water falling to the earth, requisite for the coming forth of life.

Semantic change describes the process through which the meaning of words evolve over time. In our study of the word nadah, we can see how a divinely instituted natural process for women may have been distorted by the adversary. The gift of menstruation became regarded as a mere punishment, a curse upon womanhood, and was used as a justification for an unbalanced elevation of men over women.

In contrast, prophets of this dispensation have repeatedly referred to women as instinctively caring and self-sacrificing. Joseph Smith taught, “It is natural for females to have feelings of charity and benevolence” [20] and John Taylor shared, “Sisters know how to sympathize with and administer to those who are poor, afflicted, and downcast.” [21] We seem to innately understand women’s tendency to nurture, but have been less able to acknowledge the natural process which fosters this ability. As long as this knowledge of menstruation as a gift remains unnamed and unrecognized, it can be harmful to women and a loss for society as a whole. [22]

I recently conducted an informal survey to assess how menstruation has affected the lives of the faithful women around me. The responses varied widely, as each individual female has a unique relationship with menstruation, largely framed by her personal experience. For these contemporary women, major themes surrounding menstruation included pain, fear and embarrassment about hygiene, absences from school, sports, and work, fertility and medical challenges, and emotional turmoil. Though each response was unique, menstruation had affected each one in significant ways. The repeated cycle of menstruation could be described as a woman's natural counterbalance to feelings of invincibility and pride.

A very small percentage of the women who responded indicated having a positive relationship with the menstruation process. While acknowledging the aforementioned struggles, these women also cited the deep connection with their mothers, grandmothers, aunts, sisters, friends, and daughters that menstruation brings. They described women they had never met before but with whom they shared an instant kinship and empathy while helping each other through embarrassing situations. They shared family customs they had instituted to help their daughters celebrate the initiation into womanhood. They referenced a distinctly feminine creative power that flows through their bodies and connects them with their Heavenly Mother. When we view womanly blood as a mere hygiene crisis, young women miss out on the profound, eternal significance of the blood they shed.

It is the opinion of this author that menstruation is a gift that Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother have given to their daughters to help prepare them for the rigors and responsibilities of motherhood. Menstruation demands that young women slow down and take care of themselves. Their tolerance for pain and familiarity with bodily functions increases by necessity. Menstruation cultivates sisterhood, empathy, and being in tune, which makes women uniquely qualified to meet the demands of newborn children. [23] Women are naturally caring toward others because, through menstruation, nature has made us so. We learn to nurture first through nurturing ourselves. [24]

The Lord Teaches of Birth and Rebirth

A beautiful section of scripture in the Pearl of Great Price describes the Lord teaching Adam and Eve the essentials of the gospel of Jesus Christ. The Lord expounds on agency, repentance, and redemption. He then teaches about the roles of men and women with these words:

That by reason of transgression cometh the fall, which bringeth death, and inasmuch as ye were born into the world by water, and blood, and the spirit, which I have made, and so become of the dust a living soul, even so ye must be born again into the kingdom of heaven, of water, and of the Spirit, and be cleansed by blood, even the blood of mine Only Begotten; that ye might be sanctified from all sin, and enjoy the words of eternal life in this world, and eternal life in the world to come, even immortal glory. (Moses 6:59)

Central to the plan of redemption and return is the exquisite sacrifice of the Savior Jesus Christ. His Atonement covers all, and all things bear record of him. Righteous men and women work in concert with the Savior to bring about the exaltation of mankind. In the verse above, you will notice two parallel images involving birth through water, blood, and spirit.

The first birth is our birth onto the earth, involving immersion in water and blood from the womb, and the spirit which God made. Newborn babies emerge from the womb covered in the umbilical waters and blood of their mothers. Scientists have hypothesized that the reason women menstruate is because of the assertiveness of our young. With most pregnant mammals, the embryo simply rests on the womb lining. However, the human placenta burrows into the lining of the womb. Seeking nourishment, it will dig through the lining to directly bathe in the mother’s blood. [25] The struggle between the infant and the mother for nourishment has necessitated a thicker lining in order to protect the mother. [26]

Birth from the premortal realm into mortality materializes through the water and blood of women. The first recorded birth occurred while Adam and Eve were adjusting to terrestrial life after being removed from paradise and the presence of God. Imagine the wonder that these two new parents must have felt as they experienced childbirth for the first time. They witnessed the miracle of receiving a spirit from their heavenly home through the female body. Ancient scripture records that Eve exclaimed, “I have gotten a man from the Lord” (Genesis 4:1). Adam and Eve, the sole mortals on earth, had discovered a connection to their heavenly home.

Through this womanly birth would journey every member of the human race. As tiny babes, you and I were immersed in blood and water within our mothers. Our physical bodies, together with our eternal spirits which our Heavenly Parents organized, allowed us to experience birth.

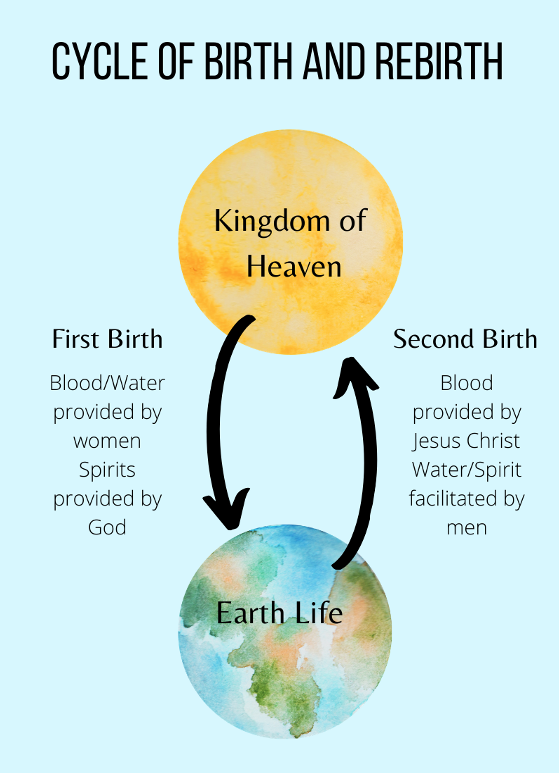

During his mortal ministry, Jesus taught the concept of the first and second births to Nicodemus, a great Jewish teacher. Nicodemus asked incredulously, “How can a man be born when he is old? can he enter the second time into his mother’s womb, and be born?” (John 3:3-8).

The second birth is a spiritual return to the kingdom of God. Like physical birth, it is made possible by water, spirit, and blood; however, the second birth takes place through the waters of baptism and reception of the Spirit, made possible by the atoning blood of the Savior. Symbolically, immersion in the waters of baptism is a return to the womb of the mother. As our physical journey began at birth, so our spiritual journey begins with baptism. The baptismal covenant and reception of the Holy Ghost initiates the return journey to the kingdom of God.

The ordinances of baptism and reception of the Holy Ghost mark the beginning of a passage from earth life to eternal life and are facilitated by men. These men, trained and ordained to offices of the holy priesthood, are qualified to guide us on our return to the kingdom of God. The second birth is patterned after the first birth, and each birth is absolutely essential for our salvation. Bruce R. McConkie taught, “Without each of these [elements of the first birth], there is no life, no birth, no mortality … Without each of these [elements of the second birth] there is no Spirit-birth, no newness of life, no hope of eternal life.” [27]

As we approach a deeper understanding of the fullness of the gospel of Jesus Christ, we can learn to seek out and teach both male and female symbolism. Whether searching the scriptures or explaining the meanings inherent in blood, water, and spirit, it is important to remember that the first and second births mirror each other. This doctrine was intentionally taught by the Savior himself to our first parents. Blood certainly represents the sacred blood of the Atonement of Jesus Christ, and it also represents womanly blood. Water symbolizes the cleansing of baptism, and it also represents the waters of the womb. Spirit is indicative of the confirming Holy Ghost, and it also takes us back to our origins as spirit children of our Heavenly Parents. [28]

Jesus concludes his conversation with Nicodemus with the words, “If I have told you earthly things, and ye believe not, how shall ye believe, if I tell you of heavenly things? And no man hath ascended up to heaven, but he that came down from heaven, even the Son of man which is in heaven” (John 3:12-13).

The Savior himself was required to come down from heaven and experience birth in order to ascend up again. Both physical birth through his mother and spiritual birth administered by a priesthood holder were necessary for his ascension. Let us not allow the symbolism of the spiritual birth to blind us to the importance of the physical, as each is absolutely vital to our progression.

The Plan of Salvation

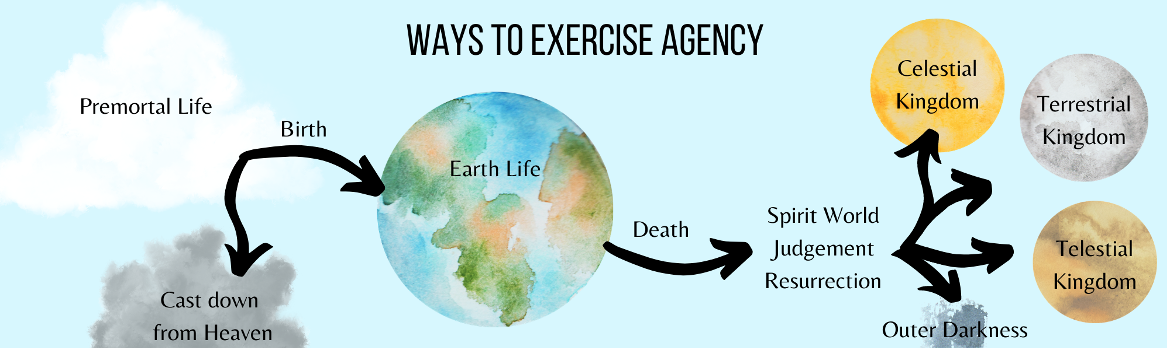

A helpful visual tool for understanding the gender parallelism inherent in the first and second births is to use the imagery of the Plan of Salvation. You have likely seen diagrams of the Plan of Salvation in a linear format, with the first stage being premortal life, then Earth life, and finally celestial life. These visuals behave like a timeline, showing us where we have been and where we are going.

Because of humanity’s current position in the Plan of Salvation, the state of mortality on Earth, we often focus on those essential choices that are ahead of us, such as the saving ordinance of baptism. However, the gospel of Christ is more than a gospel of salvation; it is a gospel of exaltation through which we can qualify to live the exalted life of our Heavenly Parents. In order to see the full picture of the plan, we must remember where we came from before this life and the righteous decisions we must have made to qualify ourselves to enter the womanly portal to earth. Let’s take a look at a depiction of the options available to children of God to help shift our focus.

As you can see, there are two crucial places along the path where our agency allows us to take divergent routes: one during premortal life, and another following the judgement. As spirit children, you and I chose to venture into mortality in order to become more like our beloved parents. There were others among us, our spirit brothers and sisters, who opted out of the Plan of Salvation. These spirits didn’t keep their first estate and were unable to progress to mortality (D&C 29:36).

On the other hand, we chose to accept God’s plan and received special preparation prior to our earthly births. As spirits, we received instruction to aid us during our Earth lives, and many were also called and ordained to perform specific work. Though we have limited knowledge of what this preparation entailed, it is consistent with our knowledge of agency that we made sacred covenants and experienced ordinances as part of our passage from the spirit realm into mortality. [29] We do not know what these holy covenants looked like, or who administered them. However, we do know that our ultimate passage between worlds was made possible by mortal women – our mothers. [30]

A depiction of the path of God’s children that is perhaps truer to the pattern of birth and rebirth that the Lord shared with Adam and Eve might look like a cycle rather than a timeline. The kingdom of heaven is at the top of the cycle, representing both our origin and our goal, and Earth life is at the bottom.

We began the journey in heaven with our Heavenly Parents, where we were faced with the critical decision of whether or not to place our faith in God’s plan and in our elder brother, Jesus Christ. The choice to become like our Heavenly Parents necessitated a Fall, a great step downward into the perils of mortality. Though it is a step downward, it is also a step forward, and it is brought to pass by women. Those who made the choice to come to Earth kept their first estate, or their first inheritance. If we each choose once again to be faithful to God and follow Jesus Christ, we will have kept our second estate and experience a return to the kingdom of heaven. [31] The ordinances of the return, this step both forward and upward, are facilitated by men through the redemptive power of Christ.

When we focus so intently on the doctrine of the path in front of us, that of a return to our Heavenly Parents through death, we may forget the doctrine of the path we have already walked. Many of our spirit brothers and sisters have yet to enter this world through the womb. As the goal for each mortal is to experience the saving ordinances, so the goal for each spirit child is to experience birth through the womb of a mortal woman. This work of bringing spirit children through the womb is ongoing. Certainly our Heavenly Parents have endowed their daughters and sons with specific, essential purposes, and their roles truly mirror and complement each other.

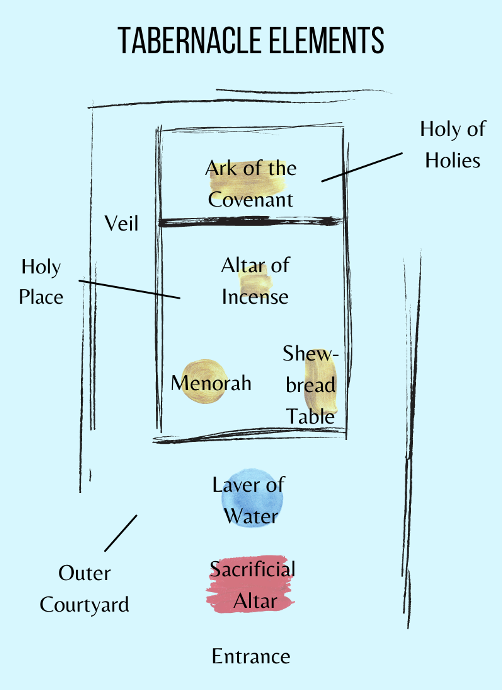

Finding the Feminine in Ancient Temple Imagery

To enhance our understanding of feminine symbolism in the fullness of the gospel, it is constructive to take a walk through the most ancient man-made temple known to Christendom, the Tabernacle. The pattern of this temple was revealed in exquisite detail to Moses, who was instructed to build this sacred space with exactness (Exodus 25:8-9). Several chapters of the books of Exodus and Leviticus are dedicated to its measurements and description, so we have a fairly accurate idea of what a walk through this temple would be like. [32]

Though many inspired men and women participated in building the Tabernacle, the children of Israel were kept from the holy place and only allowed inside the outer courtyard. Aaronic Priests had exclusive access to the tent, or holy place. And one man only, the high priest, could access the holy of holies. This ascent into the most holy place occurred once a year, during the celebration of the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16).

The temple visit by the high priest was preceded by a ritual cleansing, clothing, and anointing, much like we experience during the Initiatory ordinance in modern temples. As he entered the courtyard surrounding the tabernacle, he would encounter an altar of bronze upon which animals were ritually sacrificed and burned. The altar stood nearly five feet high and would have required a set of stairs so the priests could access it (Exodus 27:1, 5-7). Animal sacrifice on ritual altars was a sign of obedience, thanksgiving, and petition before the Lord. It was on this great altar that the blood of the sacrifices was poured out before the children of Israel.

Beyond the sacrificial altar, the high priest would find a bronze basin of water. The water was used to cleanse the priests as they went about their sacrificial duties. Once the high priest’s feet and hands were purified, he would enter the holy place, a tent woven of purple, blue, and red fabrics.

The layers of fabric and skins shielding this holy place would dim the outside light and muffle the sounds of the camp surrounding the tabernacle. The quiet sacredness of this space contrasted with the tumult of the world outside. To the left stood a massive golden menorah in the likeness of an almond tree. Its seven branches were stylized with almond leaves and flowers at their peak. This menorah was to be lit constantly, casting a glow throughout the tent. To the right was the gilded shewbread table, on which stood drinking vessels and twelve loaves of bread.

Toward the back of the room, between the menorah and the shewbread table, a small altar of incense permeated the space with a fragrant frankincense blend. It was on this altar, before the veil of the tabernacle, that the high priest would make an atonement on the Day of Atonement. He would apply blood to the four corners of the altar to cleanse and hallow it before proceeding (Leviticus 16:18-19).

The veil of the tabernacle, a massive curtain embroidered with winged cherubim, separated the holy place from the holy of holies. The holy of holies is a most sacred space which would remain shrouded and undisturbed. Accessed only by a single man on a single day of the year, the holy of holies housed one item: the Ark of the Covenant. This ark was an acacia chest overlaid with gold and containing holy items, including the very stone tablets of the ten commandments.

The cover of the ark, referred to as the mercy seat, was a work of pure gold. Two cherubim, one on the right and the other on the left, crowned the golden ark, their outspread wings covering the ark. It was within this holy of holies that the high priest might hear the voice of God from between the cherubim (Numbers 7:89).

In ancient times, this journey through the Tabernacle was the pinnacle of mankind’s interaction with God. This man-made portal, created according to the Lord’s specifications and rich in the symbology of the Atonement, connected the children of Israel with their God. However, its exclusivity and mystery also kept the covenant people at a distance (Deuteronomy 18:15-18).

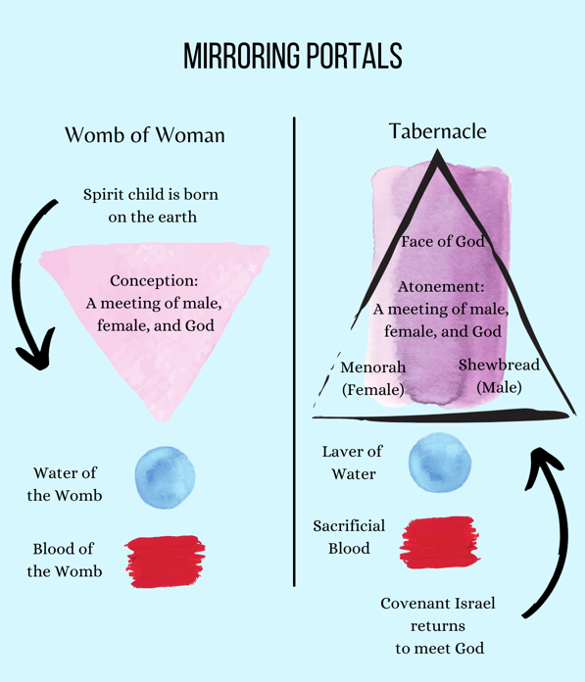

With our enhanced understanding of the key complementary roles that men and women play in the gospel of Jesus Christ, let’s explore a more personal interpretation of tabernacle symbolism.

When interpreting any form of art, it is essential to keep in mind that symbolism is multi-layered and complex. This is especially true when examining eternal symbolism, as the artist is the creator God himself. Modern temples are rife with symbolic elements. The beauty of this imagery is in the ability of a child of God to learn line upon line and layer upon layer as he or she delves deeper into the mysteries of godliness. As you consider the following interpretation of sacred tabernacle imagery, allow the Spirit to guide you and keep in mind that all things testify of Christ (Moses 6:63).

Early temple worship embodied Israel’s relationship with God. It was also deeply permeated with imagery pointing Israel to the eventual atoning sacrifice of Jesus the Christ (Hebrews 8:1-6, 9:1-15). In addition to this interpretation, the Tabernacle represents the most sacred relationship between man and woman: the covenant marriage.

Under my hypothesis, the high priest, cleansed, anointed, and wearing the priesthood garments, as the sole man who has access to the tabernacle, represents the bridegroom. He journeys past the sacrificial altar of blood, which possibly reflects the blood women shed during menstruation and birth. He cleanses in the water basin, a potential representation of the amniotic water that breaks during childbirth.

Within the holy place, he encounters emblems to his left and to his right. In traditional Semitic societies, the left (or weaker) hand represents femininity, while the right (or stronger) hand represents masculinity. An echo of this symbolism is apparent in modern temples, which are often arranged with the women on the left and the men on the right. Our high priest views to his left the symbology of womanhood and the first physical birth: a menorah stylized as a blossoming almond tree. Sacred trees, referred to in the Old Testament as asherah, often represent the mother goddess. [33] He views to his right the symbols of manhood and the second spiritual birth: a table, holy bread, and water vessels.

Before him lies a curtain richly embroidered with images of cherubim. This veil is a boundary, a separation, keeping him from the most sacred and holy place. Beyond the veil is the great mystery, a place where he can hear the voice of God. This boundary separates the physical world from the eternal. It is symbolic of the indefinable veil of mortality that keeps us from the remembrance of our premortal life and our Heavenly Parents. It also suggests the traditional veil of the bride, which was lifted upon completion of the wedding ceremony, allowing entrance to the bridegroom.

Once he has lifted the veil, he enters the holy of holies. Here he encounters the gleaming Ark of the Covenant upon which two cherubim face each other with their wings outspread.

Cherubim represent a great mystery to scholars of Judaism. They are sacred winged beasts, sometimes described with the faces of man, other times with multiple faces of lions, eagles, or bulls. They are associated with the movement of winged flight and the speed of chariots. Cherubim are the guardians who keep the way of the tree of life and appear in visions of the temple of God. However, the attitude of these cherubim, neither facing outward nor with a flaming sword, expresses a shared intimacy. [34]

The massive golden cherubim of Solomon’s Temple, made of olive wood gilded with gold, were around 15 feet high and had a 15 foot wingspan. They spread their wings above the ark, with the tips of their wings touching (1 Kings 6:23-27). In the words of one 3rd century rabbi, “When the Jewish people would ascend for one of the pilgrimage festivals, the priests would roll up the curtain for them and show them the cherubs, which were clinging to one another, and say to them: See how you are beloved before God, like the love of a male and a female.” [35]

The ordinance of covenant marriage is only partially performed in the sealing room of the temple. When couples are sealed spiritually in modern temples, their creative partnership with God is incomplete until followed by a physical union. Sexual union, a high and holy practice, unlocks the portal of the womb. Though we know little about the moment a spirit child enters the womb, we do know that sexual relations must precede the entrance of heavenly spirits into mortality.

Women’s bodies are portals that bring those spirits which God has created into mortality. The bridegroom passes beyond the blood and water of the womb and through the veil of mortality, reaching a most sacred space in which children are conceived. Within the womb there is a creative coming together, or at-ONE-ment, of male and female matter. With divine help, this intimate act allows for the manifestation of the physical body and initiates the first birth.

The Tabernacle is a portal that brings the covenant people in contact with the most high God through the mouthpiece of the high priest. His ascension represents the second birth, passing the sacrificial blood of the altar, past the baptismal laver of water, and into the spiritual holy of holies. This journey is a return to things of the spirit, a rebirth, an echo of the first birth.

According to the apocryphal Gospel of Philip, the holy of holies is the bridal chamber. [36] The sacred communion in the holy of holies between the high priest and God is a reflection of the sacred consummation between husband and wife in the bridal chamber. These holy relationships follow a pattern exemplified by the connection between Christ and his covenant people. The apostle Paul refers to the parallelism of the Christ/Church and husband/wife relationships as a great mystery in his letter to the Ephesians (Ephesians 5:22-33).

The idea of architecture symbolizing a woman’s body is a familiar metaphor in Judaism. A woman’s ritual immersion in the mikveh is often referred to as “setting the house in order” or “cleaning the house.” In Hebrew, the phrase “serving her house” is a euphemism for sexual relations. In fact, the concepts of woman and house are so intertwined that many scholars believe a reference to a house in Talmudic language, i.e. the house of Israel, actually refers to the women of Israel and the matriarchal line. [37]

According to this interpretation, the holy Tabernacle and the body of a woman are mirroring portals connecting the earth with the heavens. These passages complement each other, and each is profoundly sacred. It is the opinion of this author that when prophets were instructed to build ancient temples, God revealed to them a design that metaphorically mirrored the function and form of woman (Ezekiel 43:10-12).

Sacrificial Blood

Our Savior granted us a sublime gift in the eternal healing of the Atonement. His sacrifice brings faithful men and women back into spiritual alignment with their Heavenly Father and Mother. The Savior’s care and concern for both sons and daughters of God was readily apparent during his mortal life, and was a distinctive attribute given the culture of his time.

There were many different sets of laws to which Jesus was subject. His nation had been occupied by the Roman Empire and was therefore obligated to follow their regulations and pay their tributes. Obedience was also required for local Jewish statutes, including the religious code of the Law of Moses. In order to limit the spread of disease, the Mosaic Law codified procedures for handling physical illness. For example, a person who had an abnormal bodily emission was referred to as a zav (זב) or zavah (זבה). These individuals were pronounced unclean and required to separate from others during the emission and for seven days thereafter. The law regulated similar states of uncleanness for anyone experiencing skin diseases such as leprosy (Leviticus 15).

While a woman was experiencing separation for uncleanness, anything she touched would also become unclean. As a zavah went through her day, the bed she slept in was considered defiled and any food or drink she touched became contaminated. Wooden bowls she handled would need to be cleansed and pottery broken. The law required that these things be purified before anyone else came in contact with them, otherwise that person would also require cleansing.

The Savior understood these ritual laws. He experienced them firsthand in his daily life, observing the women in his family who were separated during their cycles or perhaps watching friends experience exclusion during illness. He would have heard the passages from the Law of Moses repeatedly in the synagogue. He would have studied and analyzed the law from his youth. However, Jesus was also a student of a higher law.

One day as he was navigating a crowded street, Jesus perceived that power had gone out of him. He stopped and asked the crowd which of them had touched him. A woman who had had an issue of blood for twelve years hid herself behind the others. This woman had been considered unclean, an excluded zavah, for over a decade. According to the law, she should never have been in the throng. When she touched the hem of the Savior’s garment, she knowingly made him unclean. Trembling, the woman came forward, knelt at Jesus’s feet, and confessed that she had touched him. She explained her situation and proclaimed that she was instantly healed. Rather than receiving the rebuke she had feared, Jesus comforted her and sent her in peace (Luke 8:43-48). It was not the only time the Savior would take upon himself the uncleanness of those around him.

Jesus Christ often healed through touch. He reached out and healed the leper (Mark 1:40-45). He took the ruler’s deceased daughter by the hand and the girl arose (Matthew 9:18-36). When one of his adversaries was wounded, he touched his ear to heal him (Luke 22:50-51). He did not allow the strictness of the Law of Moses to keep him from relieving the suffering of those around him. As the Master Physician, he adhered to a higher law.

When the Savior experienced the agonies of Gethsemane, he did so in solitude, suffering pain so intense for the sins of mankind that blood came from every pore (Mosiah 3:7). By this shedding of blood, Christ also became a zav. He willingly endured the physical and emotional heartache of the entire human family. He undertook uncleanness so that we might all rise to a higher level, as do women who undertake menstruation that all might be born. Christ’s uncleanness under the Mosaic law, like women’s, is not meant to be understood as a symbol of inferiority, but as a symbol of spiritual power. The act of the Atonement is beyond human comprehension. Only through symbolism and metaphor can the human mind begin to grasp it.

When the prophet Isaiah ministered in the days before the Savior’s mortality, he must have pondered deeply to find imagery to help his people understand the Atonement. He likened the profound sacrifice of the Savior to the struggles of a mother during pregnancy and labor. Using words like bear, born, carry, labor, and deliver he taught those with ears to hear about the sufferings of the Savior (Isaiah 53:4, 63:9). Christ himself, in anticipation of the great Atonement that he would experience, used the blood of a mother as a parallel to his own sacrificial blood (Moses 6:59).

Though no mortal could endure those sufferings and no mortal experience comes close, the imagery of the suffering of a laboring mother comes closest. [38] Mothers suffer physically for each child they carry, experiencing illness and grief as nutrients are leached from their bodies to form the infant. Babies are brought into this world as their mothers are racked with wave upon wave of pain–pain which, for some, is so damaging that death becomes their release. The precious Savior suffered such agonies, only multiplied, for each and every one of us. No mortal could have endured this pain and survived the experience. The drops of blood he shed, blood which under the Law of Moses would have made him unclean, act as a purifier for us, erasing our sins and easing our burdens (Luke 22:44).

When Moses dedicated the Tabernacle, part of the ceremony involved sprinkling the Tabernacle, the holy of holies, and even the congregation in blood (Exodus 24:8), a foreshadowing of the blood that Jesus Christ would shed. Sacrificial blood has an ultimate sanctifying effect. I submit that the blood women release, whether as a prelude to childbirth or during birth itself, is similarly sacrificial in nature. She sheds this blood not for herself, but for the soul that she brings to earth. Without her offering and the ordinance of birth, the plan could not exalt the human family. Womanly blood, a type of holy sacrifice, should be viewed with respect and honor.

Conclusion

Like the woman with an issue of blood, our young women have spent many years in doctrinal seclusion. The eternal significance of the menstrual blood they shed has been repulsed and ignored, its imagery removed from our teachings. Taboos have hushed this fundamental gift, relegating its beauty to biology alone. As a consequence, many women have lived their lives attempting to align themselves with a masculine construct that left little room for their distinctive being.

From the very beginning of mortality, the adversary has engaged in a desperate campaign against femininity, attacking the noble character of Eve, her divinely-instituted menstrual heritage, sacred intimacy and the holy calling of motherhood. His disparagement of women has been so thoroughly convincing that the doctrine of womanhood is considered obscure even among members of the restored Church of Jesus Christ.

Many of our scriptures, hymns, and teachings have sprung from doctrines written by men for a mostly male audience. Masculine interpretations and perspectives have dominated the spiritual landscape for centuries. Much that was holy has been stripped away (1 Nephi 13:26-29). Perhaps if more of the writings of the prophetesses had survived, we would have increased canonical knowledge of the hearth and of the home. It is challenging indeed for men, uninitiated in the mystery of menstruation and the transformation it affects, to fully understand its significance. [39]

Thankfully, God is not the author of confusion, but of peace (1 Corinthians 14:33). From before the foundation of this world, our Heavenly Father and Mother created a balanced plan for women and men. They designed a natural instructional process for their daughters that no fallen society could hinder and no usurper could forbid. They knew that eternal truths about women would be attacked and concealed by the adversary, and they left patterns and reflections to guide us to a return to truth. The ordinance of birth, the blueprint of the ancient temple, and the blood of the Savior all bear witness to the distinctive glory of womanhood.

Understanding the Christ-centered symbolism inherent in these feminine rites will fundamentally alter our perception of women and, more importantly, their perception of themselves.

Menstruation, that monthly cycle of pain and cleansing, prepares each daughter of God for her individual life mission. It is a preparatory process, similar to the Priesthood of Aaron, pointing young women toward the high calling of motherhood. An understanding of this feminine imagery can spark a revelatory experience during scripture study, particularly as we try to discern the Old Testament. As we teach concepts linking the personal preparations of women to the Savior of the World, our understanding of the priesthood and the Tabernacle is enriched and made more complete.

Further, as we embrace the concept of menstruation as a spiritual preparation and begin to teach it as such, our young women will better understand their value and purpose. We can break from teachings that debase, minimize, or completely omit the divinity of womanhood, and arm our daughters with a holy, empowering message about their femininity. Their bodies, both metaphorically and physically, are a sacred portal to the Most High. In many meaningful ways, a woman is a priestess to the temple of her body.

Her responsibility to tend to her temple will empower her to navigate decisions about modesty. Her responsibility to safeguard her holiest spaces will give her wisdom as she keeps the law of chastity. She will see herself reflected more clearly in the sacred words of scripture and the holy prophets, enabling her to better partner with the Savior in bringing to pass the immortality of the human family. She will understand more fully her divine role in the Plan of Salvation and, like Mother Eve, have the knowledge she needs to make wise choices in these latter days.

NOTES:

[1] Dallin H. Oaks, “The Great Plan of Happiness,” Ensign 23, no. 11 (November 1993): 72-75, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/1993/10/the-great-plan-of-happiness?lang=eng --- [Back to manuscript].

[2] “The First Presidency and Council of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” The Church of Jesus Christ, Sept. 23, 1995, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/the-family-a-proclamation-to-the-world/the-family-a-proclamation-to-the-world?lang=eng --- [Back to manuscript].

[3] Russell M. Nelson, “A Plea to My Sisters,” Ensign 45, no. 11 (November 2015): 95-97, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2015/10/a-plea-to-my-sisters?lang=eng --- [Back to manuscript].

[4] Russell M. Nelson, “Spiritual Treasures,” Ensign 49, no. 11 (November 2019): 76-79, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2019/10/36nelson?lang=eng --- [Back to manuscript].

[5] Doris M. Kieser, “The Female Body in Catholic Theology: Menstruation, Reproduction, and Autonomy,” Horizons 44 (2017): 1-27, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/horizons/article/female-body-in-catholic-theology-menstruation-reproduction-and-autonomy/463F42D08C5C47BD063E221DBC6D3AB5 --- [Back to manuscript].

[6] Merriam-Webster, “Priestess,” Merriam-Webster, accessed March 9, 2021, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/priestess --- [Back to manuscript].

[7] Bonnie H. Cordon, “Beloved Daughters,” Ensign 49, no. 11 (November 2019): 67-69, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2019/10/33cordon?lang=eng --- [Back to manuscript].

[8] For examples of possible challenges for young women see David Noyce, “Latest from Mormon Land: Church surveys members about women’s issues - from feminism to to ordination to Heavenly Mother,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 1 202, https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2021/07/01/latest-mormon-land-church/

--- [Back to manuscript].

[9] Smith speculates that blood replaced the spirit that had previously energized her body. Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, compiled by Bruce R. McConkie (Bookcraft, 1954-56), 1:57. [Back to manuscript].

[10] “רבה.” The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Hendrickson Publishers, 2001), 915. [Back to manuscript].

[11] “עצב.” The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Hendrickson Publishers, 2001), 780. [Back to manuscript].

[12] “משל.” The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Hendrickson Publishers, 2001), 605. [Back to manuscript].

[13] Shreya Dasgupta, “Why Do Women Have Periods When Most Animals Don't?,” BBC, April 20, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20150420-why-do-women-have-periods --- [Back to manuscript].

[14] See Genesis 18:11, Genesis 31:35, Leviticus 20:18, Leviticus 15:33.

[Back to manuscript].

[15] A. Gottlieb, “Menstrual Taboos: Moving Beyond the Curse,” in: Bobel C., Winkler I.T., Fahs B., Hasson K.A., Kissling E.A., Roberts TA. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_14 --- [Back to manuscript].

[16] Rabbi Hayim Halevy Donin, To Be a Jew (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 126-127. [Back to manuscript].

[17] “נדד”. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Hendrickson Publishers, 2001), 622. [Back to manuscript].

[18] “נדה”. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Hendrickson Publishers, 2001), 622. [Back to manuscript].

[19] Spencer W. Kimball, The Teachings of Spencer W. Kimball, edited by Edward L. Kimball, (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1982), 25. [Back to manuscript].

[20] Joseph Smith, History of the Church, vol. 4 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1907), 605. [Back to manuscript].

[21] John Taylor, The Gospel Kingdom (Salt Lake City, Deseret Book, 1987), 177.

[Back to manuscript].

[22] Alexandra Pope and Sjanie Hugo Wurlitzer, Wild Power, (Hay House, 2017), xiv, 28. [Back to manuscript].

[23] Christiane Northrup, Women’s Bodies, Women’s Wisdom (New York: Bantam Books, 2020), 117. [Back to manuscript].

[24] Spencer W. Kimball, Faith Precedes the Miracle (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972), 98. [Back to manuscript].

[25] Deena Emera, Roberto Romero, and Günter Wagne, “The Evolution of Menstruation: A New Model for Genetic Assimilation,” BioEssays 34, no. 1 (2011): 26-35, https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201100099 --- [Back to manuscript].

[26] John Jarrell, “The Significance and Evolution of Menstruation,” Best Practice and Research: Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 50 (2018 Jul):18-26, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29530426/ --- [Back to manuscript].

[27] Bruce R. McConkie, A New Witness for the Articles of Faith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 288-89. [Back to manuscript].

[28] Orson F. Whitney, Conference Report, Apr. 1920: 122. [Back to manuscript].

[29] Joseph Fielding Smith, The Way to Perfection (Salt Lake City: Genealogical Society of Utah, 1943), 50-51. [Back to manuscript].

[30] Sheri L. Dew, “Are We Not All Mothers?” Ensign 31, no. 11 (November 2001): 96, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2001/10/are-we-not-all-mothers?lang=eng --- [Back to manuscript].

[31] Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, compiled by Bruce R. McConkie (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1954-56), 1:65-66. [Back to manuscript].

[32] In addition to Exodus and Leviticus, I rely on the descriptions in Donald W. Parry’s 175 Temple Symbols and Their Meanings, (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2020). [Back to manuscript].

[33] Daniel C. Peterson, “Nephi and His Asherah,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 9, no. 2, article 4 (2000): https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol9/iss2/4

--- [Back to manuscript].

[34] Ugo Volli, “Cherubim: (Re)presenting Transcendence,” Signs and Society 2, no. S1 (2014): S23-S48, accessed April 28, 2021, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/674426

--- [Back to manuscript].

[35] William Davidson, ed., “The William Davidson Talmud,” Sefaria, accessed March 8, 2021, https://www.sefaria.org/Yoma.54a --- [Back to manuscript].

[36] Wesley W. Isenberg, trans., “The Gospel of Philip - The Nag Hammadi Library,” The Gnostic Society Library, accessed March 8 2021, http://www.gnosis.org/naghamm/gop.html --- [Back to manuscript].

[37] Mimi Levy Lipis, Symbolic Houses in Judaism: How Objects and Metaphors Construct Hybrid Place of Belonging (Burlington: Ashgate, 2011), 132-133. [Back to manuscript].

[38] Jeffrey R. Holland, “Behold Thy Mother.” Ensign 45, no. 11 (November 2015): 47, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2015/10/behold-thy-mother?lang=eng --- [Back to manuscript].

[39] Arthur Green, “Bride, Spouse, Daughter: Images of the Feminine in Jewish Religious Literature,” in Susannah Heschel, ed., On Being a Jewish Feminist (New York: Schocken Books, 1982), p. 249. [Back to manuscript].

![]()

Full Citation for this Article: Tilton, Becky Holderness (2021) "Temple Types and Sacred Blood: How divine patterns guide young women to Christ," SquareTwo, Vol. 14 No. 3 (Fall 2021), http://squaretwo.org/Sq2ArticleTiltonTempleTypes.html, accessed <give access date>.

![]() Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome.

Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome.