Although many non-Christian religions believe in female goddesses, the belief in a Heavenly Mother is a “cherished and distinctive belief among Latter-day Saints,” and few other Christian religions acknowledge a female deity. [2] While members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have a strong belief in the actuality of a Heavenly Mother, historically, there has not been much elaboration on this point of doctrine. However, interest among this figure in the lay community has surged in the last decade—particularly among its women members—resulting in numerous theological examinations, literary musings, and visual representations. [3] Indeed, depictions of Heavenly Mother have increased exponentially within this time frame and some members report feeling that the visual arts are an appropriate terrain in which to explore her attributes, powers, and roles. Recent studies by Kayla Bach and Charlotte Shurtz suggest, based on members’ self-reports, that art provides an important means for believers to draw nearer to her. [4]

Convinced that a large-scale, data-driven study of this phenomenon was in order, in 2020 we put together a team of researchers from across several disciplines who could combine expertise in collecting, analyzing, and interpreting its development. As authors, our goal is not to speculate or state anything about the doctrine, role, activity, or purpose of Heavenly Mother. We refer interested readers to the Gospel Topics essay on Heavenly Mother for a discussion of those themes.2 Instead, we aim to examine how Latter-day Saint artists portray Her and how this might be a reflection of the cultural climate among Church members. After identifying 505 artworks with the subject of Heavenly Mother and surveying as many of the artists as possible (approximately 50% provided data), these images were coded for an initial round of content analysis, considering components such as bodily characteristics (age, race, and body type); the use of formal elements such as light and color; dress and symbols; activities and events; contexts; and relational elements (e.g., inclusion of other divine figures such as Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ). The specific data derived from analysis of the visual attributes of Heavenly Mother-related art suggest discernable patterns of representation. These representational patterns, in turn, speak to broader cultural trends within the Latter-day Saint Church, including globalization and the increasing value placed on parity, inclusion, and belonging. But perhaps the most noteworthy aspect to this project is that it quantifies the number of artworks devoted to Heavenly Mother in the last ten years—a number that suggests interest among the Latter-day Saint community to acknowledge and reflect on Her—and that art is viewed as an efficacious space to express and meet these desires.

Literature Review

Importance of Perception of and Connection to God

A host of research studies has demonstrated that one’s conception of and attachment to the divine has significant implications for not only one’s individual religious or spiritual life, but how one perceives others and engage in the world—and gender identity and ideology play critical roles in these dynamics. In general, feeling a strong connection with God is related to a stronger spiritual constitution and religious commitment. [5] Other studies suggest that a personal relationship with deity results in better psychological functioning and mental health, and even healthier body image. [6] Conceptions of a gendered God affect how individuals live in the world. In Whitehead’s 2012 study on gender ideology and religion, they find that individuals who perceive God as solely male tend to endorse greater hegemonic masculinity norms, believing for example, that “most men are better suited for politics, a preschool child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works, it is God’s will that women care for children, or that a husband should earn a larger salary than his wife.” [7] Furthermore, those who envision deity as exclusively male are more likely to support harsh criminal punishment and militarism. [8] These studies suggest that belief in a female deity has the potential to positively affect societal norms, including a more instinctual view of women as possible authority figures.

However, there is little research on the effects of a gendered conception of deity within the Latter-day Saint community. Further, the largest scale study on Latter-day Saint beliefs surrounding Heavenly Mother (conducted in 2022) found that while many individuals desire a more meaningful relationship with Her, they do not know how to develop this. [9] These individuals reported feeling much closer to Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ, with most people reporting that they simply had no relationship at all with Heavenly Mother. Some individuals expressed frustration that She was not discussed more regularly in Church settings, and some wondered if they should have a relationship with Her. Unsurprisingly, among those surveyed, it was women who appeared most eager to know more about their Heavenly Mother and how Her existence impacted them. [10] The questions surrounding if it is appropriate to have a relationship with or talk about Heavenly Mother contributes to what has been called a ”Sacred Silence,” and some have suggested that although reverence should be the expectation, absolute silence does not protect Her, it erases Her. [11]

Art as a Means of Cultivating Connection with Heavenly Mother

There have been a few studies and philosophical forays into the role of art and visual culture in some individuals’ seeking connection to Heavenly Mother. In a small 2019 study of Latter-day Saints, some participants indicated a strong belief in a Heavenly Mother and reported that She could often be felt during the creative process, such as writing poetry and producing artistic works. [12] Indeed, several participants felt that their creativity was inherited from Her specifically. Creating the artwork in this sample seemed to be a deeply meaningful experience for the artists themselves. Many reported that the process of creating art was a way of exploring a possible connection with their Heavenly Mother. This attitude is supported by previous research by Shurtz’s 2019 study in which even non-artists talked about how the creative process functioned as a channel of connection to female deity. Because artwork can portray Heavenly Mother as someone people can identify with and relate to, some individuals who desire a greater connection to Her report viewing artwork as a way of feeling connected to and learning more about Her. In fact, 53% reported that they connected to Heavenly Mother specifically through artwork that took Her as subject. [13]

Overview of Latter-day Saint Theology about Heavenly Mother

The theology of Heavenly Mother has been discussed by Latter-day Saint apostles and leaders since the Church’s founding in 1830, but it has only been in the last 50 years or so that there has been a critical mass of discourse about Her. [14] In their pathbreaking study on the topic published in 2011, Paulsen and Pulido summarized existing quotes on Heavenly Mother from Church leaders and found over 600 distinct references to Her across the Church’s history. Since its publication, there has been a marked increase in official Church discourse regarding Heavenly Mother and Her identity as one of our Heavenly Parents. [15] In 2019, the descriptor “Heavenly Parents” replaced “Heavenly Father” in part of the official theme for the young women of the Church. [16] Over the years, church authorities have described Heavenly Mother as a “procreator and parent,” a “co-creator of worlds,” a “co-framer of the Plan of Salvation,” and “a concerned and loving parent involved in our [earthly] probation.” [17] Church authorities have referred to Her using a variety of titles (i.e., Heavenly Mother, Mother God, God the Mother, God the Eternal Mother, and the Eternal Mother). Drawing from addresses given by Latter-day Saint general authorities from 1971–2019 that discuss Heavenly Mother, Allison Welch distilled the divine attributes and roles associated with Her by Church leaders. [18] Although this discussion by Church leaders is sparse in comparison to accounts of Heavenly Father (or God) and Jesus Christ, it seems clear that Heavenly Mother is an important doctrine of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Several leaders of the Church have referred to the existence of Heavenly Mother throughout history. [19] The most recent counsel from Church leadership, given by Elder Dale G. Renlund in the 2021 October Latter-day Saint General Conference, confirms that there has not been a great deal of revelation about Her, and that “Seeking greater understanding is an important part of our spiritual development, but please be cautious.” [20]

A Brief Sketch of Heavenly Mother in Latter-Day Saint Art Tradition

While Latter-day Saint artists have represented holy women such as Mary, the mother of Christ, in their art, only recently have visual artists in the faith tradition turned to portraying Heavenly Mother. The earliest dated depiction of Her is traditionally granted to John Hafen’s illustration, I’ve a Mother There (1908), (Fig. 1) for the 1845 poem by Church matriarch Eliza R. Snow that became the beloved hymn “O My Father.” It was, however, very much an anachronistic artwork, and for the next 100 years, Heavenly Mother essentially went untouched as a subject by visual artists.

In 2012, J. Kirk Richards finished The Breath of Life (From the Dust), a monumental painting that pictures Mother in Heaven as co-creator of Adam (Fig. 2) and was displayed in Brigham Young University’s Museum of Art. This work seems to have inaugurated a new movement in the Latter-day Saint visual art scene. The vast number of artworks that take Her as subject have been executed just within the last decade. It seems possible that artists may be portraying depictions of Heavenly Mother in an effort to seek, as Elder Renlund said, "greater understanding” and comprehend themselves in their search for Deity. [21]

Although a number of artists have explored the subject of Heavenly Mother independently, it is the spate of recent exhibitions devoted to female deity that has done much to foster this new direction in Latter-day Saint art. In May 2015, Brigham Young University student Katie Payne opened her MFA show with a Mother in Heaven installation piece. [22] In the last several years, Writ & Vision, an art gallery located in Provo, Utah, has sponsored a number of exhibitions devoted to Heavenly Mother, such as J. Kirk Richards’s After Our Likeness (2016), in which he displayed several representations of holy women, including Eve, Mary, and Heavenly Mother (2016); McArthur Krishna’s Heavenly Mother and the Wise Women, an exploration in textile art (2019); the group show Visions of Heavenly Mother (2021); and most recently, Laura Erekson’s And I Call Her Mother (2022), an exhibit in which the natural world became a space for contemplating Heavenly Mother’s presence and power.

Significantly, the theme for the 2021 invitational of Latter-day Saint women artists sponsored by the “Certain Women” art collective was “Reflections on a Mother in Heaven,” which produced an exhibition of over 125 artworks devoted to the subject, a number of lectures and panels, and a substantial catalogue. The show was enormously popular and widely covered in the local press, and its hefty catalogue, complete with essays, artist statements, and illustrations, is now the most extensive published repository of Latter-day Saint Mother in Heaven artwork. [23] Just a few months after this exhibition closed, the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts gallery in New York City sponsored an exhibit, curated by Margaret Olsen Hemming, titled The Sacred Feminine in LDS Art & Theology (which also resulted in a later paper). [24] Thus, events around Heavenly Mother artwork specifically tend to be increasing in frequency.

Overview of the Scope and Methodology of the Study

While no means exhaustive, this is the first study of Latter-day Saint visual representations of Heavenly Mother conducted on such a scale and approached systematically. Intent upon conducting a content analysis of as many visual depictions of Heavenly Mother created by Latter-day Saint artists as possible, researchers amassed artworks that took Her as their subject. Artwork was included if it met one of the following criteria:

- The title indicates that the artwork is of Heavenly Mother,

- The accompanying description conveys that the work is of Heavenly Mother,

- The artist relayed that it is a depiction of Heavenly Mother in some other form,

- The art was featured in a collection of art of Heavenly Mother and does not explicitly state that it is of someone else (e.g., Mary, Eve).

Only visual artwork was included in this study (e.g., painting, sculpture, print media, and textiles), while musical and literary forms were excluded. Artwork for this study was collected by a team of graduate and undergraduate research assistants, who perused digital image databases using Internet using keywords such as “Heavenly Mother art” or “Heavenly Mother LDS”; contacting self-identified Latter-day Saint artists on social media to see if they had produced a work on the topic, and finally, attending local art exhibitions featuring Latter-day Saint artists. The end sample for this study consists of 505 individual pieces of Latter-day Saint art depicting Heavenly Mother executed in a variety of media and spanning the years 1908—2021, although the vast majority of these works were produced within the last 5 to 10 years. [25]

After these Heavenly Mother artworks were identified, attempts were made to contact the artists to complete a short survey for basic demographic information and a written description of the inspiration behind their work if one was not initially provided. Information about the artists of these works was collected to develop a profile of these contemporary Heavenly Mother iconographers. Artists were directly contacted by the research team via social media or email. If the team did not receive a completed survey after three attempts to contact the artist, research assistants filled in as much demographic data as they could find via the artist’s social media or website. [26] Of the pieces in the sample, 57% of the artists provided information, and research assistants filled in details for 17% of the remaining works. For 25.54% of the artworks in the sample, artists did not take the survey and research assistants were unable to obtain any demographic information.

Guide to Coding of Heavenly Mother Artwork

Each depiction of Heavenly Mother was first coded via Qualtrics for the following broad constructs: imagery and symbols, events, and relational figures which were then further broken down into other categories. These artworks were then scrutinized for other elements of representation particular to Heavenly Mother, which included attributes/actions, form, dress, age, race, and body type. [27]

Findings and Discussion

In this section, we offer the results of the content analysis and general conclusions about the significance of the study’s data vis-à-vis Mother in Heaven, considering how it relates to the depictions of the female divine in Christian (namely Catholic) art, and represents cultural developments within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Again, we do not offer a discussion on the doctrine, roles, capacities, or characteristics of Heavenly Mother here. Instead, we attempt to provide a discussion based on artist representation and how this might be related to the current climate and culture around Heavenly Mother among Latter-day Saint individuals.

Imagery and Symbols

Art representing Heavenly Mother possesses abundance of recurring imagery and symbols. Approximately 57% of these works included some sort of imagery or objects. By far the most common imagery portrayed involved nature, which most often took the form of trees, plants, water, earth, or flowers. Nature imagery was present in 42% of all artworks and was portrayed in 77% of the art in which imagery was depicted at all. An example of nature imagery is Laura Erekson’s Hidden in Plain Sight (2021), which displays a beautiful scene of flowers and foliage, featuring Heavenly Mother’s hands outstretched at the top if you look closely (see Fig. 3).

Imagery evoking the universe was also frequently employed; about 18% of the artwork contained some aspect or object associated with the extraterrestrial, such as stars, planets, suns, and so forth. Domestic imagery was rare; only 8% of the artwork positioned Heavenly Mother in a domestic space, such as a kitchen or bedroom. Specific symbolic objects meant to signify her were also relatively uncommon but did exist: 10% of the artwork contained a tree, 2% contained a pillar or beam of light, and 2% contained a dove. Additionally, Heavenly Mother was very often portrayed as being surrounded by a halo, either a halo of light or a small band of gold around her head (43% of all artworks).

Consistent with the long history of representing female deity in Western art, many depictions of Heavenly Mother in this sample were placed in a natural setting. She is often portrayed in a natural environment (in keeping with the Marian imagery of the enclosed garden as well as global personifications of female deity as related to the earth and its elements). Indeed, nature was by far the most used element by artists—Heavenly Mother was often surrounded by trees, flowers, vines, or other living things. Sometimes she was portrayed as Mother Earth, and in several notable examples, she had a pregnant belly encompassing the world.

The use of tree symbolism, congruent with ancient depictions of a female God in ancient Israel, represents a renaissance of this iconography among recent believers. [28] Ginger Dall Egbert’s Mother Tree (2021) exemplifies this trend (see Fig. 4), indicating that some Latter-day Saint artists are drawing upon ancient religions and iconographies of mother goddesses such as Asherah, who has been deemed “the mother of all living” and has been associated with the biblical Tree of Life.

Imagery of the universe was also popular, perhaps a nod to the belief by some that Heavenly Mother was a cocreator of the world and its inhabitants. A powerful example of this is Emily Carruth Fuller’s Heavenly Mother Watching Over Her Children (Fig. 5), which features a large mother goddess suspended in a galaxy of stars. Her hand and foot are outstretched to the planet Earth in a gesture that speaks of power and grace. Interestingly, the portrayal of Heavenly Mother in domestic contexts was rare; only a few artists imagined how She might be present in the everyday moments of humankind’s mortal life.

In terms of the use of recurring symbols, Latter-day Saint artists appear comfortable drawing from general symbols to indicate divinity (the color white, diffused light), but they seem reticent to employ more specific ones, such as doves or pillars in light in representing Mother in Heaven. Given that the dove is associated with the Holy Spirit in Christian iconography, and a pillar of light with the appearance of holy men such as Heavenly Father, Jesus Christ, or prophets in Latter-day Saint iconography, it is perhaps not unexpected that these two symbols are rarely used in visual representations of Heavenly Mother.

Events and Relational Figures

Only occasionally was Heavenly Mother portrayed as being present at a specific scriptural event (8% of all artworks). [29] When such an episode was illustrated, the most common event was the creation (55%), followed by Christ’s birth (21%). Less common were representations of Her at general birth or marriage scenes (10%), at Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection (7%), at Christ’s baptism (1%), in the First Vision (1%), or in premortal life (1%).

These results convey the artists’ perception of Heavenly Mother as an active God—one who is present in the most sacred moments. Latter-day Saint leaders have not taught that Heavenly Mother was present in these sacred events – however, we find it interesting that some members picture Her as being there in some capacity.

In terms of relational figures, Heavenly Mother was most often presented in relation to Heavenly Father. Heavenly Mother was significantly more likely to be positioned next to Heavenly Father (88% of the artwork when Heavenly Father was present) as compared to being above or below Him, or in front of or behind Him. [30] Additionally, the Heavenly Parents were most likely to shown touching (62%), compared to not touching (21%) or being merged as one being (17%). [31]

Another pattern in the study’s artworks is the representation of Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother as co-equals. As Heavenly Mother is only sometimes discussed in formal Church settings, some might assume that She is either less important than or secondary to Heavenly Father in Latter-day Saint doctrine. However, modern-day Church leaders have taught that the pattern of earthly marriage is exemplified by our Heavenly Parents, with “the divine Mother side by side with the divine Father.” [32] Artists have applied this notion of partnership to their depictions of the Heavenly Parents; in the samples of this study, we found that they are most often depicted as right next to one another and touching. A document prominent in the Latter-day Saint religion, The Family: A Proclamation to the World, states that “fathers and mothers are obligated to help one another as equal partners.” [33] Of note is that parity in family relationships is also broadly associated with positive outcomes for families. [34]

Thus, while Church doctrine suggests that while there are gender differences, men and women are of equal importance, power, and value, and thus there should not be a hierarchical dynamic between partners in a marriage. [35] Even though institutionalized religion is often criticized for placing women at a disadvantage or in a position of inferior power within marriage, many Latter-day Saint artists choose to depict the “perfect marriage” (that of Heavenly Mother and Heavenly Father) as one of closeness and equality. Given the research on the relationship between people’s perceptions of God and hegemonic masculinity (Whitehead, 2012), the Latter-day Saint belief in a Heavenly Father and a Heavenly Mother may have the power to neutralize some of the inequalities that have been noted around gender dynamics in relationships.

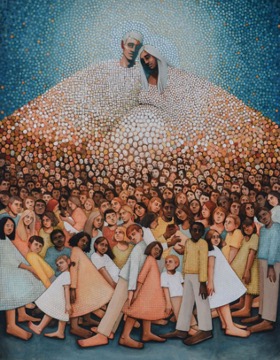

One piece of artwork that showcases this ideal in a marriage partnership is Caitlin Connolly’s In Their Image (2017), a massive painting that shows Heavenly Father and Mother embracing while looking out from the heavens over their most prized creations—the human family that fills the earthly realm pictured below (Fig. 6). The parity in positioning, size, and visual interest of the Heavenly Parents gives visual representation to the notion that the marriage ideal on earth follows that of heaven, that is, an equal partnership. It is also significant to note that this piece of art is prominently displayed at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Also characteristic of this kind of relational presentation is Kayla Becknuss’s We are in Their Image (2021), a piece that presents Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother as equal partners (Fig. 7).

Attributes/Action

Heavenly Mother was represented 55% of the time as engaging in a specific activity or possessing a particular attribute, and in a variety of different actions. [36] When in action, She was most likely to be portrayed as nurturing (35%) or protecting/watching over others (27%). Less common were pieces of art in which She was creating (12%), providing (11%), or instructing (3%) Her earthly subjects. There were also several actions (12%) that were not included in the coding metrics. The type of action did not significantly differ by race, age, or body type. Many of these depictions position Her in conventional roles associated with femininity (mother, caregiver, nurturer), or less commonly, Queen of Heaven. Unsurprisingly, Heavenly Mother is almost always portrayed in human form. As former Church President Lorenzo Snow said in 1840, “As [wo]man now is, God once was. As God now is, [wo]man may be.” [37]

In the study’s sample, Heavenly Mother was often shown playing diverse roles throughout the eternities, and actively engaging in the creation of worlds and in the affairs of Her children on earth. These depictions suggest that artists do not view Heavenly Mother as a distant and immobile figure. Instead, She is perceived by artists as a nurturer and a protector who watches over others. She is portrayed as creating, providing, and instructing. However, She is infrequently pictured in the strictly biological activities associated with that role (e.g., pregnancy, breastfeeding). The rationale behind minimizing such “bodily” elements of motherhood may be attributed to a growing recognition that not all women will become biological mothers in this world, due to infertility or the lack of opportunity.

A commonly seen “mothering” action in this study involves the embrace of or outstretched arms toward Her earthly children. While a highly unusual scenario in its specificity, Etherington’s two-paneled Mother in Heaven (Heavenly Homecoming) is typical in the sense that She is shown with outstretched or encircled arms. In this painting, Heavenly Mother is shown welcoming one of Her children (Fig. 8). Its bright color palette, lyrical brushwork, and intimate composition combine to produce a strong sense of communion and belonging.

Another recurring activity in the sample is Heavenly Mother’s act of providing. For example, Marilyn Matthews’s Mother of All (2020) where milk from Heavenly Mother’s breasts drip down to feed the rivers of the world.

In other words, Heavenly Mother’s roles and activities are depicted as being diverse in nature but often concerned with the affairs of humanity. In Brooke Bowen’s Heavenly Mother Feeding Manna to Her Children (2020), Heavenly Mother’s figure, clad in a star-spangled robe, emerges from the heavens to guard over her sleeping children and to set out bread to nourish them when they wake (Fig. 9).

Natalie Cosby’s She Wept (2020) shows Mother in Heaven hugging the earth and weeping, indicating Her divine sorrow as She weeps with the world during moments of oppression and pain (see Fig. 10).

Form and Dress

By and large, Heavenly Mother artworks by Latter-day Saint artists picture Heavenly Mother as embodied (83%) rather than in an abstracted manner (17%). This suggests that artists perceive that Heavenly Mother has a body like unto our own. An interesting outlier to this trend is artist Ben Crowder, who has produced a portfolio of digital abstract and nonobjective art devoted to Latter-day Saint deity. His portfolio includes 16 depictions of Heavenly Mother.

Heavenly Mother is also depicted wearing a variety of clothing types and decoration. [38] She is commonly dressed in robes/temple clothing (33%), in modern clothing (29%), or without clothing (e.g., shown as dressed in light; 26%). Less common are works in which She is attired in traditional clothing of various cultures (12%). She regularly is dressed in white (34%), rarely in gold (5%) and more commonly in a variety of other colors (61%). Clothing was more likely to be simple in nature (60%), compared to ornate (17%) or unknown (23%).

The nature of Heavenly Mother’s dress in the artworks of this study seems to indicate a widespread desire to create a Heavenly Mother iconography that is universally accessible and/or that suggests an engagement with the contemporary world. In about one third of the paintings, Mother in Heaven is depicted in robes similar to those worn by Mary in historical Christian art—with the exception that these robes are predominantly white, as is customary in Latter-day Saint imagery of God and Jesus Christ - rather than the customary blue, red, or pink. Another third of the artwork in the sample features Heavenly Mother without specific clothing—she is often encompassed in something else, such as light. In many world faith traditions, and particularly in the Christian one, light symbolizes common (and largely gender-neutral) attributes of the divine such as holiness, virtue, goodness, wisdom, hope, and knowledge. It is not unexpected that a sizable number of artists elected to draw upon well-established conventions in the shared visual languages in the Latter-day Saint and Christian traditions. Finally, another third of artwork in the sample portrayed Heavenly Mother in modern clothing. By portraying Mother in Heaven in modern-day clothing, female deity perhaps becomes more relatable and thus accessible to contemporary viewers, thereby fulfilling one of religious art’s key functions—to serve as an instrument for drawing closer to the divine.

It is worth noting that several artists elected to depict Mother in Heaven in culturally specific clothing, (e.g., traditional Native American clothing worn for social and ceremonial occasions). This artistic choice may be indicative of a desire for more globalized representations of deity within the Latter-day Saint community, as this would ostensibly facilitate the aim of seeing one’s self and one’s kind in the divine—which is not to be confused with the concern that one makes God in one’s own image. It may also be motivated by a desire to underscore that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is for all God’s earthly children.

Given Latter-day Saint theology regarding humankind’s origins and potential powers in the afterlife, as well as its fundamental belief that the Gospel of Jesus Christ is for all humankind, it is to be expected that Latter-day Saint artists’ images of Heavenly Mother shrink the gap between deity and humankind. It is reasonable to view key patterns relative to Heavenly Mother’s portrayal in artwork as growing out of Latter-day Saint doctrines that shrink the gap between heaven and earth.

Age and Body Type

When age could be visually determined, Heavenly Mother was always portrayed as an adult or older. She was never depicted as a child or an adolescent. Our analysis revealed that She was more likely be portrayed as a young or middle adult (71%) compared to a mature, elderly woman (19%). [39]

In many ways, the age result follows the tradition of representing the divine feminine in pagan and Christian art, in which women are typically depicted as being in their prime (i.e., of childbearing age). While the earthly mother of Jesus Christ, Mary, is traditionally portrayed as a young woman—perhaps because she was very young when she delivered Jesus or as a means of marking her eternal virginity—Latter-day Saint artists tend to depict Heavenly Mother as a variety of ages, ranging from young adult to an elderly woman. For example, in Michelle Franzoni Thorley’s Mi Madre De Los Cielos, Heavenly Mother is portrayed as a younger woman, complete with thick black braids that cascade from her head.

However, there seems to be more elderly representations of Heavenly Mother than is found in other Christian faith traditions (such as Catholicism). For example, Megan Knobloch Geilman’s 2020 photographic tableau, Pietà features a mature mother, who, according to the artist, can be understood as a representation of either Mary the mother of Christ or Heavenly Mother (Fig. 11). Drawing on traditional Christian iconography of female deity, Geilman’s work conveys the respect given to older adults in the Church of Jesus Christ. [40]

When Mother in Heaven’s body was shown, the analysis revealed that She was significantly more likely to be of an average type than of other body types. [41] Specifically, Her body is most commonly depicted as of average build (70%), or slightly less often, as a thin build (19%). Larger builds (7%) or pregnant bodies (4%) were present in the sample, but rare. Most artists (70%) depicted Heavenly Mother’s body as having an average size instead of being thin, large, or pregnant. Significantly, artists’ depictions of Heavenly Mother’s age were not statistically related to how they depicted Her body size. However, body type differed by race: thinner bodies were more likely to also be white, whereas non-white bodies were more likely to be depicted as large or pregnant. [42]

In the study’s sample, Mother in Heaven is most often rendered as being of average build, which suggests that contemporary Latter-day Saint artists may want to emphasize Her commonalities with Her earthly children by embodying Her as like and similar to them. A good example of this approach can be found in Allen Ted Busschen’s (2020) painting Creations (Fig. 12).

Latter-day Saint individuals are not immune to negative experiences that stem from the influence of “body ideal” messages (e.g., thin ideal, muscular ideal) shown in the mainstream media (Ferguson; 2018) and may benefit when media (or in this case, art) portrayals depict more realistic and relatable body shapes. [43] While average-sized bodies are more similar to thin-sized bodies than to large-sized bodies, these depictions of Heavenly Mother are approaching representations of female bodies that are more relatable and realistic. These findings are also similar to those in Olsen Hemming’s “The Divine Feminine in Mormon Art” that found that Heavenly Mother is commonly portrayed with an average body size.

Race/Ethnicity

Artists in the study’s sample represented Heavenly Mother in somewhat racially/ethnically diverse ways; almost half of the representations portray her as non-white (44%). The breakdown of this category is as follows: white (56%), Black (19%), Hispanic/Latinx (12%), Native American (5%), Asian (4%), Polynesian (3%), Middle Eastern (1%), and other (1%). [44]

Perhaps the most interesting finding of this study is that Heavenly Mother’s race or ethnicity was coded as non-white in almost half of these artworks. While this is likely a contemporary trend in the depiction of deity in other Christian faith traditions (such a comparison lies beyond the scope of this study), it is nonetheless a remarkable development, given that the Latter-day Saint Church is frequently cast by non-members as a white, American Church. Of particular interest is the fact that many of the artists do not share the same ethnic or racial identity as featured in their depictions of Heavenly Mother. Recent studies have found that Black and white Christian Americans’ perspective of God’s gender and race is related to their belief in who should hold positions of power. [45] For example, one study found that “attributing a social identity to God predicts perceiving individuals who share that identity as particularly fit to lead,” both within and outside the Christian context. [46] Thus, although the reasoning is somewhat speculative, evidence suggests that individuals who believe in a racially diverse Heavenly Mother may also believe that women and people of color are worthy to hold positions of influence both within and outside the Church. Being consistent with Christian teachings that “all authority comes from God, and those in positions of authority have been placed there by God” (Romans 13:1, New International Version), these empirical findings suggest that the artists who may not share the same gender or race as their depictions of Heavenly Mother may portray Her as such because they believe that women and people of color are worthy to hold leadership positions in the Church. This belief would align with the current policies of the Church where women do hold some leadership positions, and leadership positions are not contingent on race.

In this way, the fact that Heavenly Mother is only slightly more likely to be depicted as white versus non-white aligns with more expansive contemporary practices. Artist Kwani Povi Winder’s painting Makowa (Heaven) (2019) pictures Mother in Heaven using Native American visual markers of race, ethnicity, and culture (Fig. 13). In the painting’s description, Winder wrote about her desire to honor her mother, who is from the Santa Clara Pueblo, and to give visual acknowledgement to the pervasiveness of female deity in Indigenous religions.

Artist Survey Data: Demographics and Rationales

Researchers were able to contact and secure information from approximately 50% of the artists in the study. Of the artwork included in the study, 95% came from American artists. Other countries represented in the sample were Argentina, Bulgaria, Canada, China, England, Italy, Mexico, South Korea, Switzerland, Ukraine, and Yugoslavia. The vast majority of artwork was created by artists who identified as white (85%). However, 10% of artists identified as Hispanic/Latinx, 2% as biracial, 2% as Asian, and 1% as Native American, Black, or Pacific Islander. Most of the artwork was created by artists who identified as female (84%), though 14% identified as male and 1% as nonbinary or other. Artists ranged in age from 14 to 71 years old, with a mean age of 37.35 years (SD = 10.00). Additionally, 95% of the artwork was created by artists who identified as straight or heterosexual. The remaining artists identified as either bisexual (2%) or queer/unsure (3%). Unsurprisingly, 95% of those who produced these representations of Heavenly Mother currently affiliate with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Additionally, most artwork was created by artists who characterize themselves as professionals (72%), rather than amateur artists (26%).

Of the 505 artworks representing Heavenly Mother, 173 of these were produced by 12 artists. Interestingly, two of these 12 “super producers” of such artworks identified themselves as male. However, most artists in the study created one or two pieces related to the subject.

As part of the survey, researchers asked artists why they created a Heavenly Mother artwork (or multiple artworks) and what this kind of artistic endeavor meant to them. Some artists described ways of using artwork to specifically connect with their Heavenly Mother. For example, one artist wrote, “I’ve come to want to connect more with my Heavenly Mother. I’ve been searching for ways to feel Her presence. I saw so many wonderful artists painting her, and I wanted to connect to her by making one of my own. I’m on my journey to get to know her, and I’m so grateful anytime I hear of Her.” Others talked about their artwork representing an equal partnership between Heavenly Father and Mother. For example, one expressed the following:

My goal [in my artwork] is to portray the companionship and love that Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother have for each other and the world. They are aware of all, and love all. I also want others to see this image and think of how this applies to them personally into the eternities. This is a goal that we have to one day reach in our marriage relationships, whether in this lifetime, or in the eternities. Obviously, I do not know what they look like, but to emphasize the feeling instead of the physical attributes has been my goal.

Some artists talked about their desire for visual and material representations of Heavenly Mother and the importance of having her shown in a way that looked like them. Of her motivation for creating a work taking her as the subject, one woman of color wrote, “I wanted to see a Heavenly Mother that was mixed like me. My own mother is white and I have never looked like her. By drawing a Heavenly Mother that looks as if she could be my mother helped me cope with a feeling of belonging and love.” Others discussed their work as being representative of the divine identity and worth that each person inherently has as a child of God. As one artist stated:

You began with her. You are a reflection of Her—handmade and carefully, precisely composed. Your hair, your eyes, your skin, your soul: it all began with Her. You are created out of all the good that she is and she placed in you the same goodness, to remind you of home. To remind you of her. She breathed her empathy, patience, gentleness into your heart. She crafted her intellect, creativity, and wondering into your mind. She shaped curves, bones, softness, and strength and gently put them in place. Every inch of you is a painting of her. She lives in your heart, your mind, your curves and strength and softness. She proudly watches as you learn and lift and serve. She quietly listens to your questions, searching, and longing. She holds you and rocks you through your struggles and mourning and prayers. You began with her. She continues with you.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a radical acceleration in the production of Latter-day Saint artists depicting Heavenly Mother in the last decade. The artwork itself paints a picture of Her as a loving, involved, active, and inclusive female God who is coequal with a Father in Heaven (according to the artists’ perceptions). We know very little about Heavenly Mother or what She actually looks like. No Latter-day Saint prophet has recorded a vision of seeing Heavenly Mother, and there is no known description of Her hair or skin color, her height, weight, or mannerisms. Again, the purpose of the paper was not to speculate on the doctrine, roles, or qualities of Heavenly Mother. However, art has the power to create a perception of a hope that is likely shared by many Latter-day Saints – a divine Mother that is powerful, nurturing, inclusive, and supremely loving to all Her children. The production (and popularity) of this art appears to be representative of a cultural desire held by many Latter-day Saints to include Heavenly Mother in their lives in greater capacity.

Appendix

References

Allred, J. (1994). Toward a Mormon Theology of God the Mother. Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 27(2), 15-39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45228810

Ashdown, B. K., Faherty, A. N., Brown, C. M., Hanno, O., Belden, A., & Weeks, P. B. (2018).

Fathers and perceptions of God play an important role in psychological adjustment among emerging adults in Guatemala and the United States. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 179(5), 270–285.

Bach, K. (2021). Understanding the Seekers of Heavenly Mother [Paper presentation]. Global Women Studies Capstone Conference. Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Baker, J. O., & Whitehead, A. L. (2020). God’s penology: Belief in a masculine God predicts support for harsh criminal punishment and militarism. Punishment & Society, 22(2), 135–160.

Belnap, H. (2021). Megan Knobloch Geilman Pietà (Heavenly Mother) and the search for gyneaologies [Paper presentation]. Art & Belief Symposium, Brigham Young University Museum of Art, Provo, UT.

Belnap, H., & Coyne, S. (2022). Imagery of the Divine Feminine. In N. Woodbury, M. Brickey, & L. Erekson (Eds.), Reflections on a Mother in Heaven: Certain women, a latter-day women’s art show (pp. 133–135). Certain Women.

Bradshaw, M., & Kent, B. V. (2018). Prayer, attachment to God, and changes in psychological well-being in later life. Journal of Aging and Health, 30(5), 667–691.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (1995). The family: A proclamation to the world. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/bc/content/shared/content/english/pdf/36035_000_24_family.pdf

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (2015). Mother in Heaven. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-topics-essays/mother-in-heaven?lang=eng

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (2019, October 5). New Young Woman theme, class name, and structure announced. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/church/news/new-young-women-theme-class-name-and-structure-changes-announced?lang=eng

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (n.d.). Sacred temple clothing. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/temples/sacred-temple-clothing?lang=eng

Cohen, R., Fardouly, J., Newton-John, T., & Slater, A. (2019). #BoPo on Instagram: An experimental investigation of the effects of viewing body positive content on young women’s mood and body image. New Media & Society, 21(7), 1546–1564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819826530

Dever, W. G. (2008). Did God have a wife?: Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel. Eerdmans.

Erekson, Laura. (2022). And I Call Her Mother. [Exhibition]. Writ & Vision, Provo, Utah, United States. https://www.writandvision.com/copy-of-template-1

Ferguson, C. J. (2018). The devil wears stata: Thin-ideal media’s minimal contribution to our understanding of body dissatisfaction and eating disorders. Archives of Scientific Psychology, 6(1), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/arc0000044

Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., Campbell, W. K., Twenge, J. M., & Pargament, K. I. (2018). God owes me: The role of divine entitlement in predicting struggles with a deity. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 10(4), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000147

Holland, J. R. (2015, November). Behold thy mother. Liahona. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2015/10/behold-thy-mother?lang=eng

Hudson, V. M., & Miller, R. B. (2013, April). Equal partnership in marriage. Ensign. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/2013/04/equal-partnership-in-marriage?lang=eng

Kusina, J. R., & Exline, J. J. (2021). Perceived attachment to God relates to body appreciation: Mediating roles of self-compassion, sanctification of the body, and contingencies of self-worth. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 24(10), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2021.1995345

Leman, J., Hunter III, W., Fergus, T., & Rowatt, W. (2018). Secure attachment to God uniquely linked to psychological health in a national, random sample of American adults. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 28(3), 162–173.

Majeske, A. J., Coyne, S. M., Leavitt, C. E., & Long, A. C. (2022). “Your Mother and Mine”— Perceptions of Heavenly Mother among Latter-day Saints, SquareTwo, 15 (3). Accessed online at: https://squaretwo.org/Sq2ArticleMajeskeCoyneLeavittLong.html

McArthur, K. (2019). Heavenly Mother and the Wise Women [Exhibition]. Wri & Vision, Provo, Utah, United States. https://universe.byu.edu/2019/06/06/heavenly-mother-and-the-wise-women-exhibit-travels-from-rural-india-to-downtown-provo/

McDonald, A. (2015, May 7). BYU art exhibit focuses on a teaching Mormons regularly discuss: Heavenly Mother. Salt Lake Tribune. https://archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=2488214&itype=CMSID

Olsen Hemming, M. (2022a). The Divine Feminine in Mormon art. Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 55(1), 2–35.

Olsen Hemming, M. (2022b, January 14–March 6). The Sacred Feminine in LDS art and theology [Exhibition]. Center for Latter-day Saint Arts Gallery, New York, https://www.centergallerynyc.org/exhibitions/the-sacred-feminine-in-lds-art-theology

Paulsen, D. L., & Pulido, M. (2011). “A mother there”: A survey of historical teachings about Mother in Heaven. BYU Studies Quarterly, 50(1), Article 7. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol50/iss1/7

Peterson, D. C. (2000). Nephi & his Asherah. Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, 9(2), 16–25.

Pizzigoni, D., Fox, J., & O’Grady, K. A. (2019). The role of theistic spirituality in adolescent girls’ body esteem: A pilot outcome study. Counseling and Values, 64(1), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/cvj.12095

Renlund, D. G. (2022, April). Your Divine Nature and Eternal Destiny. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2022/04/36renlund?lang=eng

Richards, J. Kirk. (2016). After Our Likeness [Exhibition]. Writ & Vision, Provo, Utah, United States. http://brad-kramer-h73d.squarespace.com/after-our-likeness-works-by-j-kirk-richards

Roberts, S. O., Weisman, K., Lane, J. D., Williams, A., Camp, N. P., Wang, M., Robison, M., Sanchez, K., & Griffiths, C. (2020). God as a White man: A psychological barrier to conceptualizing Black people and women as leadership worthy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(6), 1290–1315. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000233

Shurtz, C. (2019). Heavenly Mother in the vernacular religion of Latter-day Saint women. Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies, 10(1), 29–57.

Snow, E. R. (1884). Biography and record of Lorenzo Snow. Deseret News.

Stauner, N., Exline, J. J., & Wilt, J. A. (2020). Meaning, religious/spiritual struggles, and well-being. In The science of religion, spirituality, and existentialism (pp. 287–303). Academic Press.

Tiggemann, M., & Hage, K. (2019). Religion and spirituality: Pathways to positive body image. Body Image, 28, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.004

Toscano, M. M. (2004). Is There a Place for Heavenly Mother in Mormon Theology?. An Investigation into Discourses of Power.” Sunstone.

Visions of a Heavenly Mother (2021) [Exhibition]. Writ & Vision, Provo, Utah, United States.

Welch, A. (2019). The eternal Heavenly Mother: Shattering a sacred silence through an examination of what church leaders have taught about her. SquareTwo, 12(1). https://squaretwo.org/Sq2ArticleWelchHeavenlyMother.html

Whitehead, A. L. (2012). Gender ideology and religion: Does a masculine image of God matter? Review of Religious Research, 54(2), 139–156. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41940774

Wilcox, L. P. (1992) The Mormon concept of a Mother in Heaven. In M. U. Beecher (Ed.), Sister spirits: Mormon women in historical and cultural perspectives (pp. 64–77). University of Illinois Press.

Wilcox, B., & Nock, S. (2006). What’s love got to do with it? Equality, equity, and women’s marital quality. Social Forces, 84(3), 1321–1345.

Wilt, J. A., Pargament, K. I., & Exline, J. J. (2019). The transformative power of the sacred: Social, personality, and religious/spiritual antecedents and consequents of sacred moments during a religious/spiritual struggle. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 11(3), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000176

Woodbury, N., Brickey, M., & Erekson, L. (2022). Reflections on a Mother in Heaven: Certain women, a latter-day women’s art show [Exhibition catalogue]. Certain Women.

NOTES:

[1] We wish to thank the artists who provided artwork and responses to our survey, as well as the army of undergraduate research assistants who collected and processed this data—we couldn’t have done this without them. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Sarah M. Coyne, School of Family Life, Brigham Young University, JFSB 2086C, Provo, UT 84602, USA. Phone: 801-422-6949; E-mail: smcoyne@byu.edu [Back to manuscript].

[2] The Church of Jesus Christ, 2015. [Back to manuscript].

[3] Majeske, et al., 2022 [Back to manuscript].

[4] Bach, 2021, Shurtz 2019. [Back to manuscript].

[5] (Wilt et al., 2019), religious identity (Kusina & Exline, 2021), (Grubbs et al., 2018; Stauner et al., 2020), [Back to manuscript].

[6] (Bradshaw & Kent, 2018; Leman et al., 2018), (Ashdown et al., 2018), (Pizzigoni et al, 2019, Tiggemann & Hage, 2019). [Back to manuscript].

[7] (e.g., Whitehead, 2012), p. 150 [Back to manuscript].

[8] (Baker & Whitehead, 2020). [Back to manuscript].

[9] (Majeske, et al., 2022) [Back to manuscript].

[10] XXXXXXX [Back to manuscript].

[11] (Toscano, 2004) [Back to manuscript].

[12] Shurtz, 2019. (N= 26) [Back to manuscript].

[13] Bach study. (N = 527) (2021). [Back to manuscript].

[14] Paulsen & Pulido, 2011). [Back to manuscript].

[15] (The Church of Jesus Christ, 2015; Holland, 2015). [Back to manuscript].

[16] (The Church of Jesus Christ, 2019). [Back to manuscript].

[17] (Paulsen & Pulido, 2011, p. 76). [Back to manuscript].

[18] Welch, 2019 [Back to manuscript].

[19] Paulsen & Pulido, 2011 [Back to manuscript].

[20] Renlund, 2022 [Back to manuscript].

[21] (Allred, 1994) [Back to manuscript].

[22] (McDonald, 2015). [Back to manuscript].

[23] Belnap & Coyne, 2022. Woodbury et al., 2022. [Back to manuscript].

[24] Olsen Hemming 2022a, 200b [Back to manuscript].

[25] Although an intensive search was conducted, it is likely some relevant art was missed that should be contained in the analysis. We apologize to any excluded creators of Heavenly Mother artwork for the unintentional oversight. [Back to manuscript].

[26] For this sample, research assistants used demographic information only explicitly stated by the artist. [Back to manuscript].

[27] Twenty undergraduate coders were split up into six different groups, each coding a different broad category. Coders spent several weeks completing pilot training, and then within their groups they coded 30 pieces (6% of the total sample) to establish reliability. We used Krippendorff’s alpha to calculate reliability, and each alpha met a minimum threshold of α > 0.60. [Back to manuscript].

[28] Dever, 2008; Peterson, 2000 [Back to manuscript].

[29] χ² (1) = 342.23, p < .001. [Back to manuscript].

[30] Heavenly Parents placed adjacent (χ² (2) = 134.54), Heavenly Mother placed above or below Heavenly Father (p < .001) or in front or behind him (χ² (2) = 50.96, p < .001). [Back to manuscript].

[31] χ² (2) = 37.22, p < .001). [Back to manuscript].

[32] (The Church of Jesus Christ, 2015). [Back to manuscript].

[33] (The Church of Jesus Christ, 1995, paragraph 7). [Back to manuscript].

[34] (e.g., B. Wilcox & Nock, 2006). [Back to manuscript].

[35] (Hudson & Miller, 2013). [Back to manuscript].

[36] χ² (5) = 116.01, p < .001). [Back to manuscript].

[37] (Snow, 1884). [Back to manuscript].

[38] Clothing types [χ ² (3) = 40.94, p < .001] and decoration on clothing [χ² (2) = 136.15, p < .001)]. [Back to manuscript].

[39] χ² (1) = 71.58, p < .001). [Back to manuscript].

[40] (Belnap, 2021). [Back to manuscript].

[41] χ² (3) = 364.25, p < .001). [Back to manuscript].

[42] χ² (3) = 16.60, p < .001). [Back to manuscript].

[43] (Cohen et al., 2019). [Back to manuscript].

[44] χ² (7) = 720.26, p < .001). [Back to manuscript].

[45] (Whitehead, 2012) [Back to manuscript].

[46] (Roberts et al., 2020, p. 1310). [Back to manuscript].

![]()

Full Citation for this Article: Sarah M. Coyne, Ashley LeBaron-Black, Jane Shawcroft, Megan Gale, J. Andan Sheppard, Chenae Christensen-Duerden, Megan Van Alfen (2023) "“The Heavenly Mother Artwork Project," SquareTwo, Vol. 16 No. 1 (Spring 2023), http://squaretwo.org/Sq2ArticleSOFLHeavenlyMotherArtwork.html, accessed <give access date>.

![]() Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome.

Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome.