AUTHOR’S PREFACE

It is unlikely that you have ever heard of the so-called 1857 Aiken Affair, an event that took place later in the same year as the Mountain Meadows Massacre in southern Utah. In the 1970s, I wrote a play based on the research of Juanita Brooks about the MMM and John D. Lee, great-great-grandfather incidentally of Utah’s current Republican senator Mike Lee. The play, titled “Fire in the Bones” (a favorite phrase of Brigham Young’s from the Old Testament’s Book of Jeremiah) was awarded a grant for its performance to a Salt Lake-based theater Walk Ons, then operated by several former BYU theater graduates. I also received a monetary award for having written it. At the time of its presentation, I was directing the BYU Study Abroad in Vienna and so never got to see it. A few years later, I shared the play with then BYU President Rex Lee, John D. Lee’s great-grandson. This was his kind response after reading it:

“I have always struggled with why any rational human being could have done what my great-grandfather and others did on September 11, 1857. I still don’t understand it. But I get more of an insight from your play than I ever had before. It’s not that you present any more facts. I knew them all. It is the context. Maybe it is partly your writing skill. I’m sure it is, but I doubt you could have written an essay that would have recreated the dynamics that may have existed in Cedar City on that Sunday evening quite as helpfully as did your play.”

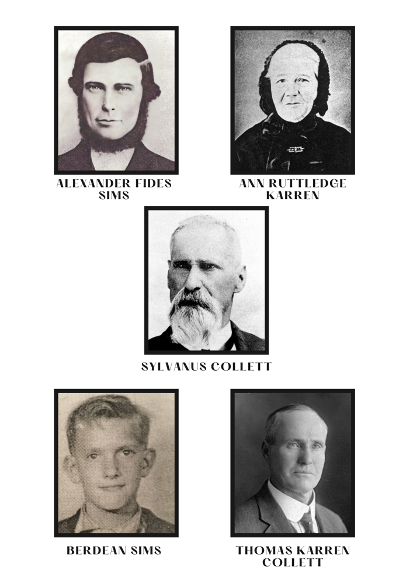

Toward the end of my retirement as a member of the BYU faculty in 2000, I then also wrote an ancestral play titled “First Trump” (referring to John’s expression for the First Resurrection in the Book of Revelations.) That play focuses on my maternal great-grandfather Sylvanus Collett’s involvement in the Aiken Affair. In 1857, Collett had just returned as a young LDS missionary to Lehi, Utah, which had been settled by, among others, his parents and the parents of his future first wife, Lydia Karren. Shortly after his return home, he was appointed the constable of Lehi and then with another renowned Lehi resident, Orrin Porter Rockwell, assigned to be escorts for two of four well-provisioned gentiles from California who upon Brigham Young’s call to various outlying church colonies to return to Utah as Johnston’s Army was then approaching Utah, had attached themselves to those then residing near the Sierra Mountains in Nevada’s Carson County, probably for a safe escort through Indian territory. There were then, in all, six men in the Aiken party, so named for two brothers with that surname. Upon arriving in Brigham City, however, they were found to have on them papers of introduction to Colonel Johnston from a U.S. military officer in California—which created the suspicion that, during the period that Territorial Governor Young had declared martial law, the Aiken group were government spies.

Four of their number were assigned personal escorts by local officers of law and order—Collett and Rockwell in Lehi and two others from Nephi. They were to escort the four—all riding horses—back to California by the “southern route.” (For whatever reason, the other two members of the Aiken party remained in Salt Lake City, one of whom managed to escape and return to California and the other the victim of a murder at Wasatch Hot Springs by a desperado called Wild Bill Hickman) It appears that one of the principal reasons for the Aiken party’s travel to Utah was to establish a gambling concession to take advantage of the wages of the members of Johnston’s army.

Few Utah or LDS historians have written about the Aikens. The only sources I have so far encountered that reference the Aiken affair are the biography by Salt Lake Tribune editor Harold Moroni Schindler, Orrin Porter Rockwell: Man of God, Son of Thunder (University of Utah Press, 1993), and Thomas G. Alexander’s Brigham Young and the Expansion of Mormon Faith (University of Oklahoma Press, 2019). For my play about Collett, however, I also relied on the complete microfilmed transcript of the notorious federally instigated trial twenty-one years later in 1878 in Provo, which lasted for several weeks and in which Collett was the lone defendant. Conveniently, Rockwell had died just the year before. At the time, the trial prompted outcries both in the media and from pulpits throughout the country decrying “the Church of Mountain Meadows.” Just as the march of Johnston’s Army in 1857 was, incidentally, the longest such event in U.S. history, the MMM is to this day considered our nation’s worst historical massacre. Collett’s trial ended in a hung jury, which absolved him of being sentenced, while in the two years prior, John D. Lee’s trial ended in his being condemned to execution by a firing squad of federal soldiers. The entire next to last act of my later play “First Trump,” which is a fanciful account of both Collett’s and other ancestors’ personal stories, derived from family records and told to one another as they come out of their graves during the First Resurrection, is essentially a verbatim copy of the Salt Lake Tribune account of Collett’s trial, and its persecution witnesses’ testimonies provide a detailed account of the Aiken Affair. I wrote “First Trump” and the equally enigmatically titled novel The Book of Lehi in which it is now embedded and in it attributed to one of Collett’s contemporary descendants like Yours Truly. The reason for the novel’s title becomes clear as one reads it.

Collett’s story and the Aiken Affair strike me as especially relevant just now with the findings of the recent publications by LDS historians Richard E. Turley and Barbara Jones Brown’s Vengeance Is Mine: The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath and Janice Johnson’s Convicting the Mormons: The Mountain Meadows Massacre in American Culture. I find that the subject matter of my novel The Book of Lehi and its embedded play “First Trump” very much coincides with that of their publications about the MMM and in a parallel fashion resembles what we now know about the Aiken Affair in 1857 and my great grandfather’s involvement in it during his trial in 1878.

I am persuaded that both John D. Lee and Sylvanus Collett were subsequently scapegoated for dutifully obeying their government authorities, who were also their ecclesiastical leaders. In both cases, each male victim was assigned a local escort ostensibly to accompany him peacefully out of Utah Territory until upon a sudden oral command, each escort drew weapons and mortally attacked the man he was in charge of. This modus operandi had to be prescribed and orchestrated by perhaps the same higher authority.

The object lesson from both events—the MMM and the Aiken Affair—is that when faced with similar demands, we can ill afford to support such actions or engage in them ourselves when we are faced with our own ethical challenges. Lee and Collett were well-intended men who under higher orders as otherwise accountable American citizens and Christlike disciples, seriously lapsed morally. Or as in my novel’s last line, the adopted Indian Lehi rhetorically asks, “He killed for the Kingdom, didn’t he?” When I directed the BYU Honors Program, our faculty and students were introduced to a book by Stanley Milgram entitled Obedience to Authority that forcefully made the same point. We must each respond to such crises according to our own conscience and individual inspiration. Call it personal revelation. The speeches by my great-great grandmother Ann Karren in the final act of the novel’s embedded play, convey the most significant ethical and spiritual insight—that if we can, with forgiveness, still accept and claim various offenders as ours, surely a loving Deity will also.

EDITOR’S NOTE

As an undergraduate at the University of Utah in the 1950s, Thomas F. Rogers double majored in both political science and theatre. He spent his first two years of graduate study at the Yale School of Drama, writing plays for the noted New York critic John Gassner. In 1983, he received the Association of Mormon Letters Drama prize. While at the 1998 Mormon Arts Festival Awards Ceremony in St. George, he was cited by Eugene England as “undoubtedly the father of modern Mormon drama.” A professor of Russian language and literature, Rogers has published monographs in that discipline. In 2016 the BYU Neal A. Maxwell Institute also published his essay collection Let Your Hearts and Minds Expand, previously reviewed by Square Two. In all, he has written twenty-nine plays.

Besides serving on the faculty of the Church’s flagship university for thirty-one years, he was privileged to serve as a missionary in Germany ten years after WWII (including Latter-day Saints in Communist-controlled East Germany) and then presiding over the LDS Russia St. Petersburg Mission a year after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Later he coordinated the visits of Latter-day Saints from the eight Russian missions to the Sweden Stockholm Temple. As a Patriarch for eight years of the Europe East Area, he bestowed over 2,600 patriarchal blessings in Russia, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Armenia, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. Not to mention, refresher courses in Russian at Moscow State University and brief residencies in Communist controlled Rumania and Yugoslavia and in Soviet occupied Poland, as well as in Syria. Later, alongside his wife after retiring from BYU, he taught English to graduate students for the BYU China Teachers Program at Peking University in the Communist PRC. In all of these instances, he found value in fostering relationships with people from many previously opposing backgrounds.

For all the Collett, Karren, and Sims descendants, who by now are legion. And for the astoundingly articulate polymath Marcus Smith, long-standing announcer and interviewer at KBYU-FM, whose own ancestors Samuel Pitchforth and John Kienke, citizens of Nephi, also played some part in the Aiken affair. Marcus’s assiduous investigations and our passionate exchanges richly enhanced the telling. Also, with special thanks to my granddaughter Jacqueline Noel for her assistance as my copy editor.

Also dedicated to my cherished former BYU colleague Gary Browning

“And behold, it is wisdom in God that we shall obtain these records that we may preserve unto the children the language of our fathers.” (1 Nephi 3:19)

“The blasphemy against the Holy Ghost, which shall not be forgiven in the world nor out of the world, is in that ye commit murder wherein ye shed innocent blood, and assent unto my death, after ye have received my new and everlasting covenant, saith the Lord God; and he that abideth not this law can in nowise enter into my glory, but shall be damned, saith the Lord.” (Doctrine and Covenants 132:27)

“And now I, Moroni, proceed to finish my record concerning the destruction of the people of whom I have been writing.” (Ether 13:1)

DEPARTURE

Ogden, Utah—The Present

I dab at the cut on my chin. It angers me. I know it’s because I didn’t want to leave home on this pleasant fall weekend and lost my cool. Took it out on my own face like some nerd. I’d much rather stay at home and watch football. Even go to church day after tomorrow.

What’s so liberating about the great outdoors? This frontier fetish about getting your five point buck? Prove you’re from a line of hunters, not wimpy gatherers? Good frontier stock and still their equal? Besides, I’ll just give the meat away to some homeless center. And why did Janice insist I shave? Bet that was the last thing our ancestors thought of when they went for game. It’s such an outworn ritual, like so much else he puts up with. Civilization? Faux wilderness? These days there’s little difference. And I got little sleep last night just thinking about where I had to go.

But my cousins prevailed again. Can’t let them think I’m anti-social, that family isn’t important. And this time Jerry said he had some hot new stuff about our great-granddad. It’s sure to be scandalous. Wonder how Earl will take it. What a contrast—the wily professor, always hoping to upset you. The religion teacher is full of denial and ready to uplift. Maybe I can get a little more shut-eye as I tune out on them.

Janice brings me a small bandaid and, as she applies it, a nice wet kiss. My lunch is ready too. Everything else got packed last night—gun, ammo, sleeping bag, trail mix. As usual, Jerry will provide canned beans and franks, pancake mix, and all the cooking gear. I’ve got to stop off in Provo on the way down to see a client or two. May not get there much before sunset. Tomorrow’s the big day. And, if they’re still short a stag or doe, Sunday too. Let’s hope the critters are close in, waiting for the kill.

“If I’m not back on Sunday, tell Harold I’ll go home teaching another time.”

“Not to worry, sweetie. Remember Ben, it’s called ‘strengthening family ties.’ And ‘building a relationship of trust.’”

“Another mini-mission, huh? Okay, I’ll try not to get trunky.”

Out the door I go, the air still cool. All the way to Nephi and from there to Burraston Ponds, as they call it these days. Or, as pedant Jerry says, Bottomless Springs—back then its Indian name—Pungun. What’s he getting at with all that trivia? Why did he insist we find our deer so far away this time—so far to the south? Mystery Man will spring it on us tonight, I suppose. Around the campfire. Dark all around. Animal noises. Embers flying in your eyes. That’s when he’ll say, ‘Boo.’ But guess what, Jerry? I ain’t afraid.

RITE OF PASSAGE—LEHI

Burraston Ponds near Salt Creek (Nephi)—1854

Sun straight above us. Hot. Piute chief drags me off pony. Then my sister. Been riding for two or three suns. Sore. Can’t walk fast, can’t run from them. Chief binds our backs together. Can’t see her now, or soothe her. Only seven winters along—my little sister. We squat together in tall bunch grass by this little lake. They dip their gourds and drink. Then give us some. Don’t know their language. Don’t know what they have in mind. Yes, I do. Mustn’t think about it. Taste the cool water. Stare at mountains, trees. Count their leaves.

Then two Whites show themselves. Come closer. One speaks our language. Not well, but well enough. He translates. Chief tells them this a sacred place. Dead ancestors weighed with rocks and put in water. No bottom. Go to ghost cave. Chief’s squaw just put there. Needs slave. Me or sister? Maybe both. Take me!!

Whites not happy. Chief will send us both to ghost cave, or only one. Whites must buy the other. Take sister!! I die for you, my sister. Quiet! Swallow your cries, your heavy breathing! More angry talk. Then loud noise from chief’s iron stick, his rifle…Ears still ring, but I hear White Man. “For God’s sake, yuh savage!! What have yuh done???” Am I dead? Not dead. Back and neck wet now. Not water. I see on shoulder—sticky and berry red…Sister quiet, too quiet. No whimper now, no breathing, no pressing my back. Slack…Kill ME now! Kill me too! No want this place—no want you, Piute, or you, White Face!

“Alright. We’ll take the boy then. No more bloodshed, hear? An’ don’t come ‘round anymore with yer treacherous tricks. Next time there’ll be a posse waitin’—bigger than all yer Piute braves put together. Now untie him.”

Whites take grain bags and tanned hides from pack horse. “There. That’s all I have. Now come here, lad.” Braves undo cords, push me to him. Must not turn ‘round. Only look ahead. Straight ahead…

“How old is he?”

Translator says, “About sixteen winters.”

“Good. I’ll take him into my household…What tribe are you, son? They didn’t even tell me. And what about that poor young girl, now at the bottom of this deep pond? I take it she was your sister. I’m real sorry…I am Samuel Pitchforth. You can address me as Brother—no. I’m going to be your daddy and adopt you. Make you into a Mormon. Give you a decent life. Bring you out from the wilderness and away from this heathen Babylon—like the Lord did your Father Lehi. And that’s what we’ll call you too—Lehi. So your name is now also Pitchforth. Lehi Pitchforth. I know you can’t understand what I just said, but we’ll make sure you speak English before long and can maybe even read it… Now let’s get going.”

CAMPFIRE

Burraston Ponds—The Present

Just like old times. Tent set up. Fire going. They’ve both already been here an hour or more. Those two are real wilderness freaks, alright. Beans still taste good when you’re hungry though. I’ll say that much for the outdoors—sharpens the appetite. So here I am, as usual, seated between them. To referee, I guess. Let ‘em talk away then.

“This is a spooky place, Jerry. Who’s crying out there?”

“A dead papoose.”

“Yeah. Right.”

“At least the Indians think so. It comes to the surface when the sun sets, contorting itself and calling for a rescuer. But if anybody tries to help it, they’re pulled in and carried to the bottom— to the Indians’ ghost cave.”

“I see.”

“Of course, that’s just a legend. Helped keep their children in line.”

“Out of the Indians’ own Brothers Grimm.”

Now Jerry stands and, with his glove on, retrieves a tall metal canister from off the grill. I see it coming—the old ritual.

“Coffee, Earl?”

As Jerry knew he would, Earl declines.

Then to me. “Ben?”

I’m half tempted. But that would make us complete allies.

I decline too, and Earl lets out a visible sigh.

Then Jerry again. “What you’re really hearing is a great horned owl.”

“Is that why you brought us here, Jerry? Is that this year’s stunning ‘revelation’?”

“No, Earl. I’ve got something closer to home.”

“Meaning?”

“It’s about our common ancestor.”

“Sylvanus?”

“Good guess.”

“Sylvanus was a good man. They all were. Faithful Saints. Too faithful, I’d say. That’s the problem.”

“You’re always tearing things down, Jerry.”

“Things?”

“Especially the Church and what’s sacred.”

“If any of it’s true, it can stand the scrutiny of scholarly investigation.”

“I agree, Jerry. But the facts still need interpreting. And even history is not pure science.”

“I concede that, Earl. But let’s just look at a few incontrovertible facts you probably didn’t know about.”

“Such as?”

“Did you know Sylvanus went to trial in 1878 in Provo?”

“As a matter of fact, yes.”

“Did you know, Ben?”

“Think I heard about it. But that was long ago.”

“Remember what for, Ben?”

“Accused of killing some man, as I recall.”

“That’s right. For a crime he committed at least twenty years earlier—in the same year, same season as Mountain Meadows.”

“For a crime he’d committed two decades before? Guess they didn’t have any statutes of limitations for trials back then.”

“At least he wasn’t convicted.”

“It was a hung jury, Earl—all Mormons.”

“Some of them ‘Jack Mormon,’ I’ll wager. Just like at John D. Lee’s trial the same year where they all voted against him—a complete hanging jury.”

“Lee was executed by a firing squad.”

“We won’t go into that just now. But Sylvanus’s trial—the evidence. Have you examined that?”

“A time or two, Jerry, you’ve hit us with some real doozies. That right, Ben?”

“He’s got a bag full.”

“So, guess what, Jerry? I just happened by the U of U library a few months ago, looking into family history. That’s when I noticed you’d put a hold on several books that also interested me—including the trial transcript. So, for once, I had an idea of what you’d try to spring on us. But this time I did my homework too. In fact, I wrote it up in the form of a play.”

“You and your plays, Earl, that no one ever produces. You should stick with teaching seminary.”

“Did you bring anything with you—any documents?”

“They’re all in my head.”

“Well, I brought mine in my play. A script for each of us. The trial’s arguments are strictly factual. And I intend for the three of us to read it with the help of this kerosene lamp.”

“Lordy.”

“Come on, Jerry. How often have we had to indulge your sarcastic spin about all kinds of sensitive issues? My turn now. Whaddaya say, Ben?”

“It can’t be worse than what I’ve heard out of both your mouths a number of times. Just joking.” “I take that as an assent. Two to one. Here are the copies I made for each of us.”

“What’s it called?”

“First Trump.”

“Not about a certain president?”

“No, Jerry. It’s from the Book of Revelations. About the Resurrection of the Righteous. Hope to see you there someday.”

“Come on, Earl. That’s not history—family or any other kind. It’s wishful thinking and pure speculation.”

“I foresaw your objection, Jerry. That part of my play is just a fanciful frame, but it serves a purpose. You’ve got to be patient, Ben willing. Now you indulge me, Jerry, the way both of us have always put up with you. That’s fair, isn’t it?”

“Alright. I’ll listen.”

“And read one of the parts?”

“If I have to.”

“I’ve assigned the major roles to fit our personalities. I will read Sylvanus’s father-in-law, Alexander Sims.”

“That addled Scotsman?”

“You want to be Sylvanus, Jerry?”

“The villain, huh?”

“I said he was a good man, didn’t I?”

“Despite what he did?”

“Let’s wait and see. Ben, I’ll have you take the role of Sylvanus’s son, Tom Collett. Later in the play, when it’s suddenly set in Cape Town, South Africa, I’d also like to have you read another part whose speaker is quite different from either Sylvanus or you. It will test your talent as an actor.”

“I’ll give it a try.”

“And I’ll start it off by reading Alexander’s lines. Since I served my mission in Scotland, I think I’m up to sounding like he may have. Have another hot dog, boys.”

“Sure.”

“Why not?”

“As the stage directions tell us, Act One takes place on the old cemetery hill in Fish Haven, Idaho. Alexander, attired in a dark, tattered nineteenth-century suit, sits on a grassy knoll and stares before him. He’s preoccupied with flying insects that occasionally light on him. Suddenly we hear an elaborate trumpet fanfare.”

“Louie Armstrong maybe?”

“Probably not.”

“OK, Shakespeare. Let’s read on…”

FIRST TRUMP

Act I

Pioneer Cemetery in Fish Haven, Idaho overlooking Bear Lake—The Anticipated Future

(ALEXANDER SIMS, played by Earl, sits on a grassy mound dressed as Earl described him. He looks toward the sky until the music ceases.)

ALEXANDER: (in a thick Scottish brogue) Wha’ in’ th’…Whoo’s playin’ tha’ troompet? Never heard sooch a wild tune, ‘cept maybe from them Zulus…(slapping at invisible insects) Well, bite, why don’ yuh? So I least have a chance tuh catch one o’ you critters an’ give yuh wha’s fer. Why ain’ yuh bi’in’? Yur as bad as soom fish…(touching his sleeves) An’ wh’ abou’ these rags? Never wore noothin’ like this before…!

(In her seventies, Sylvanus Collett’s mother-in-law ANN KARREN approaches Alexander. She wears a floor-length, long-sleeved dark dress and a Queen Victoria indoor bonnet. She carries a cloth-covered basket.)

ALEXANDER: Good day, mum. Can I assis’ yuh?

ANN: (in a distinct British accent) I’m looking for my husband.

ALEXANDER: Ain’ seen anoother body all day. Yur the first. Where yuh froom?

ANN: Lehi.

ALEXANDER: Wha’ brings yuh here, might I ask?

ANN: Instructions in a note. It was pinned to my dress. With a train ticket to Montpelier.

ALEXANDER: ‘Ow was the ride?

ANN: Smooth as ice. Sped like a bullet. Didn’t see another passenger though. Not one.

ALEXANDER: Walked here froom Moo’pelier did yuh?

ANN: Just a small hike, it was. Nothing like crossing the plains. I’m to wait here to meet my grandson, Tom Collett.

ALEXANDER: Wha’s his line o’ work—yer gran’soon’s?

ANN: He ranches with his father, Svlvanus.

ALEXANDER: Where at?

ANN: Cokeville. Seems like an age since I last saw him. You a Latter-day Saint?

ALEXANDER: Indeed I am, mum.

ANN: I’ve a concern…You could call it a sorrow.

ALEXANDER: Wha’s tha’, mum?

ANN: This same grandson—Tommy, named for my late husband—was never baptized. And now he’s a grown man, already twenty.

ALEXANDER: W’y ain’ he a Moormon?

ANN: Our daughter Lydia died giving birth to him. Maybe that embittered Sylvanus. My husband, Tom Karren, blamed Sylvanus for neglecting her.

ALEXANDER: How so?

ANN: He has five wives. But so does my Tom Karren.

ALEXANDER: Lord save us. Muhself, I never pursued th’ Pri’ciple.

ANN: That’s not the reason. It’s Sylvanus’s vigilanty-ism.

ALEXANDER: One o’ them marrauders, is ‘e?

ANN: He’s from a good family. We came to Lehi together with its first settlers. Sylvanus was the town’s first constable. Then a sheriff’s deputy. Tried to advise that U.S. Army Colonel O’Connor against perpetrating the Bear River Massacre in Idaho, but O’Connor wouldn’t listen—which is why the big U.S. Army’s slaughter of squaws and papooses and why so many soldiers also lie to this day in the military cemetery east of Salt Lake they named for that Mormon hater, Steven A. Douglas. Sylvanus had also been a missionary at Fort Limhi on the Salmon River and now justice of the peace in Cokeville.

ALEXANDER: A lawman then?

ANN: And murderer.

ALEXANDER: Yuh mean it?

ANN: Accused of it anyway. Had a big trial in Provo eight years back. He was let off though. Couldn’t agree on a verdict.

ALEXANDER: Tha’ Sylvanus?! Sylvanus Collett, yuh mean?

ANN: That’s right.

ALEXANDER: Then yer gran’soon’s a Collett too. Not Tom Collett?

ANN: Of course. And he married your daughter Catherine. We call her Kate.

ALEXANDER: What? When?

ANN: Just las’ year…

ALEXANDER: Yuh said his father’s trial was joost eigh’ year ago?

ANN: That’s right.

ALEXANDER: Wha’ year were tha’ then?

ANN: ‘78.

ALEXANDER: Beg yer par’on? Yuh know w’a year this is, mum?

ANN: Why, yes, love. It’s 1886.

ALEXANDER: An’ yer gran’son an’ muh daugh’er Kate was marrie’ afore then? Yuh recall how they met?

ANN: It’s a story we never tire of telling in the family: When your daughter Kate was still in her late teens, a girlfriend in Cokeville, they tell us, invited her to come from Bear Lake to its annual parade on Fourth of July. A handsome young horseman rode past them—our grandson Tom Collett—and your Kate asked her friend, “Who’s that?” Her friend mentioned his name but then added that he was already engaged. Your impish Kate answered, “We’ll see about that.” And the rest is history… Now who’s that?

(SYLVANUS COLLETT (played by Jerry), in his mid-sixties, grey and gaunt, appears from offstage and approaches them. He wears a plain dark turn-of-the-century men’s suit.)

ALEXANDER: Afternoon, stranger.

SYLVANUS: How’s it goin’?

ALEXANDER: Same as ever, ’cept fer them pesky ’squitoes.

SYLVANUS: Don’t bother with ’em. Ain’t bitin’ no more.

ALEXANDER: Noticed that too, did yuh? Nothin’ more fierce than Bear Lake ’squitoes. Unless it’s Bear Lake hoorse flies. You from ’roun’ here?

SYLVANUS: Wyomin’.

ALEXANDER: How’d yuh get here with no hoorse?

SYLVANUS: Walked. Been walkin’ fer a day or two.

ALEXANDER: Wha’s yer business?

SYLVANUS: Supposed to meet a feller here. Got a job fer me, I guess. Note says he’d give me further instructions.

ANN: Another note?

SYLVANUS: Yeah. It was pinned to this funny suit I’m wearin’.

ANN: Where was that?

SYLVANUS: In a green place like this one.

ALEXANDER: Soun’s soospicious.

SYLVANUS: Oh, I’m used to rendezvous-in’.

ALEXANDER: ‘Ow’s tha’?

SYLVANUS: My line of work. What’s yours?

ALEXANDER: Miller. Pu’ in th’ first burr mill in these parts.

SYLVANUS: How’s business?

ALEXANDER: Joost finished a canal ‘twixt Swan Creek an’ Sain’ Charles. We’ll ‘ave plenty o’ wa’er now—muh seven soons an’ me an’ all our neighboors. An’ lo’s moore whet tuh grind. Took muh boys an’ me seven year tuh blast through tha’ mou’ain over there.

ANN: Seven years with seven sons. Sounds like a fable.

ALEXANDER: No fable, mum. Celebration was goin’ to be tomorrow. A brass band was even comin’ from Mon’pelier to play for it. I got a li’le tipsy, I’m afraid. Cannot recall anything else.

ANN: I’ll tell you then, Brother Sims. Are you sitting down? Because the night before the celebration you went to the canal to check the dam behind your mill race—but you fell in, hit your head on a boulder, and drowned….

ALEXANDER: Yuh mean it? I’ve really been dead then? Cannot believe it.

ANN: For a long time too. I’m sorry, Alexander.

SYLVANUS: Where you from?

ALEXANDER: Name’s Sims—Alexander. Born in Scoo’land. Bu’ we coom here, me an’ Lizzie, froom Sooth Africa.

ANN: Africa?

ALEXANDER: Wen’ there as a miller’s ‘ppren’ice, an’ tha’s where we me’ th’ Moormon elders an’ become han’cart pioneers. I were th’ first miller in Sugar House, then Liberty Park an’ Centerville, where muh daughter Kate was born—

ANN: My grandson Tommy’s wife.

ALEXANDER: Tha’s right. An’ finally we settled here at Bear Lake…So how was th’ trip here…froom Wyomin’?

SYLVANUS: Strange. Didn’t see another soul. An’ that was from way up on a mountain.

ANN: What mountain?

SYLVANUS: Well, I started for here yesterday mornin’. Then decided I’d make a detour an’ climb what some say is the tallest peak in these parts—in the high Uintas—always wanted to. Never got to it till now.

ALEXANDER: Tha’s a near eighty-mile detour.

SYLVANUS: Anyway, when I reached the pass at the base of it—’bout 11,000 feet up—it was just a plain of boulders as far as you could see. There’s several peaks right there at the pass. I picked what looked like the tallest an’ up I went. Giant boulders all the way—huge steppin’ stones piled on each other like ridges on the spine o’ some ol’ dinosaur. Nice view at the top. Just one lone red-tailed hawk out there in the far distance, floatin’ on a current of air. Not above me either—but way below.

ALEXANDER: You was tha’ high, was yuh?

SYLVANUS: An’ all so still an’ quiet. No squabblin’, no cantankerous-ness. No outlaws anywhere to hunt down an’ put away.

ANN: Put away?

SYLVANUS: Sometimes. Sometimes you have to…That was ’bout four in the afternoon, judgin’ by where the sun was. Goin’ back, I told myself I’d never get to camp afore dark an’ maybe freeze to death up that high unless I avoided the trail and lowered myself over one o’ them steep shale slopes just down from the pass—no zig-zags, no meanderin’.

ALEXANDER: How deep were the slope?

SYLVANUS: 4,000 feet, maybe. Couldn’t see the base of it from halfway down.

ALEXANDER: So yuh di’n’ know if it migh’ be too steep farther down?

SYLVANUS: Took my chances. Them boulders wobbled each step I took. Couldn’t trust ’em. So I moved slow motion, strainin’ my legs an’ gettin’ weaker with the effort.

ALEXANDER: If yuh had toppled, yuhdda lost yer balance an’ kept toomblin’, I bet.

SYLVANUS: Fact is, I did just that.

ALEXANDER: How far did yuh tumble then?

SYLVANUS: Half the slope.

ALEXANDER: An’ lived duh tell it? I see no scra’ches, no bruises.

SYLVANUS: A mystery, ain’t it?

ALEXANDER: ’Tis surely.

ANN: Maybe you’re one of those three Nephites. You take a lot of chances.

SYLVANUS: Yeah (winking at them), maybe I am. So watch yerselves, hear…?

ALEXANDER: Or yur a spirt.

SYLVANUS: Think so?

ALEXANDER: I were a spiritualist afore I were a Moormon.

SYLVANUS: You may be right about that. An evil spirit too. At least accused of it…How long you been in this place?

ALEXANDER: Since early this moorning. An’ starin’ at th’ lake out there. Can’ ge’ muh fill o’ it. Like I’d joost seen it anew. Same ol’ lake though, an’ beautiful as ever. Look at tha’ deep blue. An’ all th’ trout in it. Seems like I been starin’ a’ it all day. Still, somethin’s different.

SYLVANUS: Like what?

ALEXANDER: Like this tattered suit I’m wearin’.

ANN: (to herself) He’s already forgotten.

ALEXANDER: Ain’ mine. Yer clothes don’ look mooch be’er.

SYLVANUS: I wondered about that too. These ain’t my rags. That’s for sure.

ALEXANDER: An’ where’s muh wife Lizzie….? (looking behind him) Cannot see our cabin back where it use’ tuh be. Hope she ain’ lost. Miss ’er bad…

ANN: And there’s all this confusion about what year it is.

SYLVANUS: You must both have a bout of amnesia. We’re already into the Twentieth Century.

ALEXANDER: Coome on, man!

ANN:What year do you say it is?

SYLVANUS: 1901.

ALEXANDER: Yur demented, surely!

(Whistling is heard from offstage.)

ANN: Who’s that?

ALEXANDER: Soom kid loiterin’.

SYLVANUS: Oughta be out in the fields helping his pa.

ALEXANDER: Or a’ school…Maybe he’s yer messenger.

SYLVANUS: Don’t think so. Note says he’ll be wearin’ a uniform.

(BERDEAN SIMS, sixteen and unusually thin, walks hesitantly toward them. He also wears a conservative dark suit, vintage 1940. In each hand he holds a tall, capped plastic ice cream container with a straw protruding from its top.)

ALEXANDER: Whacha got there, laddie?

BERDEAN: Raspberry shakes. One’s fer you. Didn’t know you’d have company.

ALEXANDER: ‘Shakes’? What’s a ‘shake’?

BERDEAN: You mix ice cream with fresh raspberries. They sell them at all the stands this time of year.

ALEXANDER: Moost be oother folk ou’ there then—runnin’ them stands.

BERDEAN: A few.

ANN: Where do you get the ice, love?

BERDEAN: They make them in machines.

ALEXANDER: Tha’ so?

BERDEAN: Better eat yours before it melts. Use that straw.

ALEXANDER: What straw? This one’s made o’paper.

BERDEAN: (handing the other container to Ann) Here. Take mine. Already ate a couple on the way here.

ANN: Why, thank you, love.

BERDEAN: (to Sylvanus) Sorry, I don’t have another.

ANN: (drawing on her straw) Mmmm. Delicious.

ALEXANDER: (handing his to Sylvanus) Here. Try mine.

SYLVANUS: Much obliged…

ALEXANDER: Whoose boy are yuh?

BERDEAN: Everett and Buelah’s.

ALEXANDER: Everett is one o’m uh sons.

BERDEAN: And that makes me one of your grandsons. But I wasn’t born till after you…you’re sitting down, ain’t you?

ALEXANDER: Acoorse I am—on this here hillock. But Everett ain’t yet married. How could he be yer daddy?

BERDEAN: He married in’ 94.

ALEXANDER: Don’ fool me, laddie. Tha’s next year.

BERDEAN: I’m glad you’re still sittin’ down.

ALEXANDER: Why’s tha’?

BERDEAN: I got a shock too when I found out where I was and how much time had gone by.

ALEXANDER: Whaddaya mean?

BERDEAN: I was sixteen when I died. But that’s how old I still am, seems like.

ALEXANDER: So you’re supposed to be soome kind o’ spook too, are yuh? Well, I know all ‘bou’ ‘em an’ had lots tuh do with ‘em.

BERDEAN: I know.

SYLVANUS: How coome yuh know?

BERDEAN: You was a spiritualist when you was in Africa.

ALEXANDER: Shh!

BERDEAN: And I’m no spook. I’m resurrected.

ALEXANDER: Yu’r wha’?

BERDEAN: Right now is the morning of the First Resurrection.

SYLVANUS: Who told yuh?

BERDEAN: Can’t rightly say. There’s lots of messengers.

ALEXANDER: Lookie here, laddie. I’m fifty-eight year ol’, an’ yur joost a w’ipper-snapper. I seen a lo’a things an’ been a lo’a places you still ain’t. Starin’ out way oop in Aberdeen.

BERDEAN: I know. That’s why they say they named me Berdean but didn’t quite spell it right…

ALEXANDER: Well, if I’m a resurrected bein’, w’ere’s muh Lizzie?

BERDEAN: She’s waitin’ fer you to claim her.

ALEXANDER: Where?

BERDEAN: Just down the road over the Utah border in Garden City.

ALEXANDER: Wha’s she doin’ there?

BERDEAN: What we’ve all been doin’. Me an’ my folks—your sons and daughters, their kids an’ theirs, an’ theirs too.

ALEXANDER: Doin’ what?

BERDEAN: Lyin’ stretched out, facin’ East.

ANN: You mean?

BERDEAN: That’s what I’ve been tryin’ to tell you.

ALEXANDER: Everet married in ’94, yuh say? Wha’s the year now?

BERDEAN: Can’t say. At least a century later. Maybe more.

ANN: Good heavens!

ALEXANDER: Think we’re all resurrected too then, laddie?

BERDEAN: Look around you. Where you’re at…

ALEXANDER: Yeah. There’s tombstones everywhere. (to Sylvanus) Wha’ green place was you in two days back?

SYLVANUS: Kinda like this here.

ALEXANDER: Tombstones too?

SYLVANUS: Yeah, now I think of it.

ANN: And where I was in Lehi too.

BERDEAN: (to Alexander) See that hole way over in the corner? That’s where you were. It was practically the first grave up here.

ALEXANDER: Why’s that?

BERDEAN: ‘Cause you died so early—practically the first one in the settlement.

ALEXANDER: Where’s all th’ others?

BERDEAN: Haven’t come out yet. Still waitin’ for the next trump. Or the next. You must of been good enough folks, or you wouldn’t be sittin’ upright yet either. Me? Guess I was too young an’ weak to be much of a sinner.

ALEXANDER: Resurrected, huh? Tha’ why the ‘squitoes ain’ bi’in’?

BERDEAN: That’s right. From now on we’re supposed to make peace with ’em. Like the lamb an’ the lion.

ALEXANDER: Think they’re resurrected too?

BERDEAN: Why not? Couldn’t sin, could they?

SYLVANUS: Every time they ever bit me, boy, it was sure a sin. Don’t know ‘bout you.

ALEXANDER: Woonder if tha’s w’y they’re so thick now—cause it’s all th’ ‘squitoes that ever was. All the way back tuh Adam.

SYLVANUS: That would be a heap, wouldn’t it? With all the other animals.

ALEXANDER: ‘Twould, surely. No’ tuh mention all the plan’s—trees an’ grasses. An’ all we ever ate? Think they’ll be resurrected too?

BERDEAN: Can’t say.

ALEXANDER: ‘Twould crowd us off th’ Earth, I’m thinkin’…if yur no’ foolin’ us, laddie, wha’ did I die of? I already forgot.

BERDEAN: Spirits.

ALEXANDER: Shh…So the spirits finally go’ me, did they?

BERDEAN: Not the kind you’re thinkin’ of. You drank too much before the day the canal went through that you and your seven sons had spent seven years building. Before the celebration, you fell in an’ drowned.

ALEXANDER: Damn!

BERDEAN: Yeah, bad luck.

ANN: Just a small indiscretion, Brother Sims. But fatal.

ALEXANDER: Dooble damn!!

ANN: What did you die of so young, love?

BERDEAN: Swallowed a tack.

SYLVANUS: Did yourself in with a tack?

BERDEAN: Didn’t mean to. Picked it up off the floor as a baby when I just started to crawl. It lodged in my lung. They couldn’t get it out, so I just kept coughin’ up blood and phlegm and havin’ infections. We’d go down to the doctors in Salt Lake to see what they could do, and I’d sell newspapers on the street to help pay for it. Each time they’d drain some of the fluid from my lung. That’s wha’ finally did me in. The last time, the doctor’s instrument broke a vessel and the phlegm poured into my bloodstream. I was gone in an instant. At least that’s how it was explained to me.

ALEXANDER: Who did th’ explainin’?

BERDEAN: Other messengers…My illness was a real worry for Momma. I know it aged her. An’ when I suddenly died like that…musta broke her heart.

ALEXANDER: So yuh never ’ad a family o’ yer own.

BERDEAN: Hey, I’m only sixteen. But I can now.

ANN: You think so, love?

BERDEAN: That’s the promise, ain’t it? For those who come forth with the First Trump?

ALEXANDER: (nodding toward Sylvanus) How’d you die, mister?

SYLVANUS: Have no idea. Must’ve went fast, like you. Maybe a heart attack.

BERDEAN: What’s yer last memory—before sittin’ up again? Where was yuh?

SYLVANUS: Visitin’ in Salt Lake.

ANN: In the year ‘01, was it?

SYLVANUS: That’s right.

ALEXANDER: Well, if you was goo’ ‘nough fer that ‘First Troomp,’ then so was my Lizzie. She’s gotta be up too an’ wai’in’ already. When did she die?

BERDEAN: Twenty years after you. That’s why they buried her in Garden City. None of your kids stayed around here. The ones that moved there took her in an’ bought plots so they could all be together. Me too.

ALEXANDER: An’ left me here.

BERDEAN: Didn’t want to disturb you.

ALEXANDER: Joost as well. Th’ view here’s better.

BERDEAN: You’ve got quite a progeny.

ALEXANDER: Yeah, we had thirteen yoong ‘uns.

BERDEAN: How many more by now, you suppose? Grandkids like me? And ‘greats’?

ALEXANDER: You tell me. You go’ all th’ answers.

BERDEAN: Not so many as some since you weren’t no polygamist.

ALEXANDER: Thank th’ stars fer tha’. How many?

BERDEAN: More ’n a thousand.

ALEXANDER: Holy catfish!!

BERDEAN: Finished your shakes?

ALEXANDER: Yeah.

SYLVANUS: Not bad.

ANN: Truly delicious.

ALEXANDER: Always ‘ad great berries ‘roun’ here. Well, le’s ge’ goin’. ‘is a goo’ three hour tuh Garden City.

SYLVANUS: (rising) Meanwhile, I’m goin’ down to the lake an’ catch me a fish. If that messenger comes askin’ fer me, have ’im wait.

ALEXANDER: Won’ take long if th’ fish er bi’in’ as usual…

(Sylvanus leaves.)

BERDEAN: Strange fellow. What’s his name?

ALEXANDER: Di’n’ ask. Maybe one o’ them three Nephites.

BERDEAN: You believe in them?

ANN: They’re in the Book of Mormon, love. You must read it sometime.

ALEXANDER: Well, le’s ge’ goin’. Gotta help Lizzie.

BERDEAN: We can’t go to Garden City yet. That’s why they sent me here. To let you know.

ALEXANDER: Wha’ abou’?

BERDEAN: Business.

ALEXANDER: Business?

BERDEAN: We’ve all got some. Mine was gettin’ hold of you.

ALEXANDER: Wha’s mine?

BERDEAN: First, you’ve got to go north to Montpelier and take a train to Salt Lake. But that’s just the beginning. The conductor, who married your daughter Kate—

AlEXANDER: Wha’??

BERDEAN: —will meet us here.

ANN: Tommy works for the railroad now, does he? That must be why I got a free ride to Montpelier.

BERDEAN: He should show up any time now.

ALEXANDER: ‘is dady Sylvanus was soomeone t’ reckon with. Joost as soon keep muh distance froom his son too. Leastways, not git on his wroong side…

(Sylvanus, now dashing and in his early twenties, appears in buckskin on another part of the stage. The others seem not to notice.)

OTHER WHITE MAN’S VOICE: Alright, you redskin sneaks. What you after now?

INDIAN’S VOICE: Me want speak with father.

OTHER WHITE MAN’S VOICE: This here’s Colonel Collett of the Utah Nauvoo Legion. Whaddaya think, Syl?

SYLVANUS: Well, boys, yer mean old daddy’s under arrest fer what he did in Smithfield in the late Indian War.

OTHER WHITE MAN’S VOICE: Let ‘em talk to him, Syl.

SYLVANUS: Alright, bring him out…

OTHER WHITE MAN’S VOICE: Just be careful, is all.

SYLVANUS: Don’t worry. I been ambushed enough times already… Just don’t you boys try nothin’, understand…?

OTHER WHITE MAN’S VOICE: Hey, there! Get away from him. Look, Syl, the old man’s bolted…

(Sylvanus calmly raises an invisible rifle, takes aim and shoots into the audience. A shot sounds.)

OTHER WHITE MAN’S VOICE: By golly, Syl, you got the old geezer. I think he’s plumb dead. And did those braves scatter. I do believe, Syl, you could hit a fly’s heel at a thousand yards with a blank cartridge…

(The lights fade on Sylvanus.)

ALEXANDER: No, don’ know ‘ow close I’d wanna gi’ tuh tha’ Sylvanus. So why ‘ave I gotta talk tun his soon? Why’s he my Catherine’s ‘oosban’ an’ no’ soome oother?

BERDEAN: He’ll have your ticket and tell you the rest. It’s the order of the Church, you know. We accept our calls—wherever they send us.

ALEXANDER: So th’ Church is still with us?

BERDEAN: In principle.

ALEXANDER: An’ is tha’ all he has tu’ do, this Tom Collett? Joos’ ‘an’ me a ticket?

BERDEAN: And reconcile his father-in-law to Sylvanus. With your encouragement.

(Alexander eyes Ann.)

ALEXANDER: Is this life noo differen’ from th’ oother one?

ANN: You ever hear of free agency, Brother Sims?

BERDEN: We’ve still got to make the good things happen.

ALEXANDER: So I’m tuh take a train, am I? Never rode many trains. ‘Twas mostly hoorse an’ booggy—an’ all th’ way froom Missouri by han’cart.

BERDEAN: This Tom Collett will give you two tickets—one for the train and another for an airplane. That’s why you’re going to Salt Lake. To the airport.

ALEXANDER: ‘Air Plane’? Some kinda flying carpet? An’ how far will tha’ take me froom muh Lizzie afore I can claim ’er?

BERDEAN: How’d you like South Africa again? Cape Town? Port Elizabeth?

ALEXANDER: Back to muh in-laws if they’re still alive?

BERDEAN: Or resurrected.

ALEXANDER: Oh, yeah. Resurrected. Lizzie’s moother is a Boer, yuh know. Her father’s Irish.

BERDEAN: That’s what I hear—a Boer and then some. That’s, I believe, why you’re going back to Cape Town.

ALEXANDER: Oh no, yuh don’. I paid muh dues. Been there an’ done tha’. An’ I’m far too ol’. Besides, w’y shoul’ I?

BERDEAN: I’ll tell you why, Grampa. You need to go there or do whatever else you’re asked because until every last one of us has filled his or he assignment—including my future eternal companion—none of us—and wherever there were any differences—all must now be ‘reconciled.’ I think that’s the word they’ve been battin’ around.

ALEXANDER: They?

BERDEAN: The messengers.

ALEXANDER: So tha’s the deal, is i’?

BERDEAN: That’s the deal.

ALEXANDER: An’ how many most I claim in all, did yuh say? Besides muh Lizzie?

BERDEAN: Over a thousand.

ALEXANDER: Sufferin’ catfish! An’ they’ve all most be ’reconciled’ too?

BERDEAN: At least to the third or fourth generation. We’ve been given a thousand years for that if we need it.

ALEXANDER: Wha’s yer name agin?

BERDEAN: Berdean.

ALEXANDER: Oh, yeah. A-a-a-a-berdeen, an’ mis-pronounced. Well, Berdean, when will muh soon-in-law show up?

ANN: Yes, when? I’m especially so anxious to see him again.

BERDEAN: Any time now.

ALEXANDER: Will I ever git back here? Fer keeps, I mean?

BERDEAN: Probably.

ALEXANDER: Because—look a’ tha’ lake oot there, will yuh? She’s as deep as Loch Ness. Even, soome say, wi’ her very oown moonster.

BERDEAN: Did you ever see it? The monster?

ALEXANDER: Joot oother moonsters. Moonsters an’ demons.

BERDEAN: The spirits?

ALEXANDER: Some dark winter nights they beat me tuh th’ groound, coomin’ home late froom

th’ mill. Shh...! (He steps toward the footlights and, starting to writhe, falls to the ground.)

STRANGE VOICES: Stay with us, Alex…

ALEXANDER: (still writhing) Yuh canno’ make me.

VOICES: If you don’t, we will destroy you.

ALEXANDER: Wha ‘fer? If yur really muh friends, like yuh always claimed you were?

VOICES: You know too much. You’ve seen the other world. You’re an initiate—one of us.

ALEXANDER: Yuh ain’ noothin’ tuh me any more.

VOICES: That doesn’t matter.

ALEXANDER: I’ve found soomthin’ full o’ love an’ light—soomthin’ far be’er.

VOICES: That doesn’t matter.

ALEXANDER: I’ll lean on muh Loord then an’ call yer bloof. Take me if yuh can.

VOICES: We’ll torment you then—torment you forever.

ALEXANDER: Go ahead!

VOICES: (fading) You’ll be sorry…sorry…sorry…sorry…

ALEXANDER: (to the others) They never fergive me that I fersook ‘em fer Christ’s priesthood. But I saw tha’ priesthood woork miracles far moor powerful. Helpful neighboors was prayed tuh muh sick wife in muh absence. Tha’ first winter in Salt Lake I was fellin’ timber in the Oquirrh Mootains fer a tanner whoo said he’d take care o’ Lizzie an’ our first sets o’ twins. They’d have starved if I hadn’t been fer those like tha’ man who were truly faithful. (He turns and faces the auditorium.)

MAN’S VOICE: How’s it goin’, neighbor? How’s the wife and kids?

ALEXANDER: Strange. While I was away, Lizzie fainted, she says, from bein’ so weak. She was lyin’ there oon th’ col’ floor, with chills an’ fever—the babies untended. An’ then you shoow oop an’ git ’er intuh bed. Fed ’em all too an’ give ’er a blessin’. An’ straigh’ away she gets be’er. I believe yuh saved muh family.

MAN’S VOICE: Brother Sims, I’d swear you’d come to my window just a while before. Tapped on it several times and asked me to come over soon as I could.

ALEXANDER: How could I? I were far ooff in th’ mootains.

MAN’S VOICE: No you wasn’t, Brother Sims. I swear it was you at my window. Or I’d of never thought to look in on your loved ones…

ALEXANDER: (turning again to Berdean) Oothers coome back froom th’ shadow o’ death under muh own hands—praise be tuh God, whoose Spirit quickened ’em as it flowed through me… Joost you look ou’ there, laddie, a’ tha’ goorgeous blue lake, them loomin’ moontains. There’s th’ gloory already, don’ yuh see, laddie? The paradisiacal gloory. An’ if I am finally privileged tuh inheri’ this Earth with soome oothers, tha’s all I’ll ever wan’. There can be noothin’ be’er…(looking offstage) Now who’s’ tha’ man in a uniform? He moos’ be…

BERDEAN: I’ll be movin’ on then. See you in Garden City, Grampa… (He leaves.)

ALEXANDER: (calling to him) Sure hope so…!

(TOM COLLETT (played by Ben), in his mid-sixties and wearing a conductor’s uniform, walks toward them from another direction. He carries a sheaf of documents.)

ANN: It’s another stranger. Thought it was to be my grandson.

TOM: Gramma Annie!

ANN: Don’t get fresh with me now, mister.

TOM: Don’t you recognize me?

ANN: It can’t be…my Tommy Collett? He’s…he was only twenty when I…Is it really you, Tommy love?

TOM: Yes, Gramma.

ANN: How old are you then?

TOM: I’m sixty-five.

ANN: When did you…die?

TOM: 1931, they tell me.

ANN: So it’s really that much later.

TOM: A lot later than that, they say.

ANN: (finally embracing him) Oh, Tommy, love. My Lydia’s son…. This is all so awkward. Do you remember the tall willow in my front yard, Tommy?

TOM: Yes, Gramma.

ANN: And the long rope ladder that hung from its highest limb? How you used to love to swing on it whenever you and your father Sylvanus came to see us. You’d swing and swing for hours on end.

TOM: Not when I got older, Gramma.

ANN: And what a handsome young man you were then, love. But why you were never baptized, Tommy, and why you weren’t allowed to I’ll never understand… (to both men, uncovering her basket) Have one of my crumpets. They’re mighty tasty.

ALEXANDER: (taking one) I’m sooprised we still require noorishmen’.

ANN: Maybe we don’t. But let’s hope we’re still allowed the pleasure.

TOM: (handing papers to Alexander) These are your instructions.

ALEXANDER: So yur really muh Kate’s ‘oosban’? ‘ow ol’ are yuh?

TOM: Sixty-five.

ALEXANDER: Amazin’!

TOM: What is?

ALEXANDER: I’m only fifty-eigh’.

ANN: At least I’m slightly older than the rest of you. But my Tom Karren would only be Tommy’s present age.

ALEXANDER: I’m tol’ Lizzie soorvived me by twenty year. Tha’ makes her fourteen year muh senior. Think they’ll make an adjoos’ment—bring oos all back tuh our prime?

ANN: What age would that be?

ALEXANDER: I’d settle fer thir’y. When yuh think they’ll swi’ch us back? Our ages?

ANN: Not, I imagine, before the reunion.

ALEXANDER: Reunion?

ANN: With all our kin.

ALEXANDER: So yur really Tom’s Gramma? An’ yer ‘oosban’ had foor oother wives? Bet yuh had a lo’a kiddies.

ANN: Eleven in all. Together we’ve had, I’m told, sixty-four grandchildren and, with my husband’s four other wives, a total of ninety-three. By now his offspring numbers, believe it or not—I consulted with another early riser at the Lehi cemetery, a man who knows calculus—close to a million.

ALEXANDER: Gloory! There wer’n’t tha’ many in th’ entire territory.

ANN: Can’t help it. It’s higher arithmetic. By now our descendants would have joined up with practically every other family from back then. Exciting, isn’t it—we’re all one big clan.

(Sylvanus, older again and dressed in his dark burial suit, meanwhile settles, unnoticed, on a tombstone upstage from the others.)

ALEXANDER: What’s excitin’? There still ain’ soome folks ’roun’ here.

ANN: Who, for instance?

ALEXANDER: Muh wife. Yer ’oosban’. An’ all our chil’ren. An’ now we got tuh head in th’oopposi’e direction.

ANN: Patience, brother. You must have done a lot of good. Or they wouldn’t trust you with this new mission.

ALEXANDER: In tha’ sky vessel?

ANN: That’s right.

ALEXANDER: (to Tom) Wha’ is muh mission, by th’ way?

TOM: It’s on account of your wife.

ALEXANDER: Lizzie?

TOM: Her ancestors.

ALEXANDER: Th’ Dootch or Irish?

TOM: Others, farther back. Cape Town must have been quite a melting pot.

ALEXANDER: Who else then?

TOM: (referring to his documents) Well, Elizabeth’s maternal line—she may not have even known herself—goes like this: her great-grandfather married a woman whose forebears were Chinese, one of them for a time the governor of Indonesia, later sent by the Dutch East India Company as a political exile to Cape Town.

ALEXANDER: So I’m hooked oop with a bunch o’ Asians…

TOM: It doesn’t stop there. And this is the problem. Another Boer ancestor took for wife the daughter of two more Indonesian exiles with Semitic names, Moses and Sarahm— Maylays and possibly Dutch slaves.

ALEXANDER: When was tha’?

TOM: 1600s.

ALEXANDER: Tha’s a loong time ago.

TOM: Not long enough.

ALEXANDER: Fer wha’?

TOM: This couple had Old Testament names, but they’re also names from the Koran.

ALEXANDER: So?

TOM: They were Muslims whose descendants, when they intermarried with the Boers in South Africa, became Christians.

ALEXANDER: Goo’ fer them.

TOM: This is also, unfortunately, known to the Muslim Sheiks and Imams in Cape Town and in Jakarta. It’s been their practice to execute those who leave their religion.

ANN: Gracious!

ALEXANDER: Savages, tha’s wha’ they are. No better ’n African Kafirs an H’ootentots.

TOM: Of course, they can’t execute anyone anymore.

ALEXANDER: W’y’s tha’?

TOM: Death’s done with—remember?

ALEXANDER: Oh. Fergo’!

TOM: However, just as you and I are hoping to claim our posterity, so are the followers of Allah, worldwide.

ALEXANDER: The Lord will have soomethin’ tuh say ’bou’ tha’.

TOM: That’s our hope.

ANN: A principle of our Faith.

TOM: They have a similar conviction.

ALEXANDER: ’Cept we know who’s righ’—who’ll be th’ winner.

TOM: That’s how they see it too.

ALEXANDER: Where’s all this headin’?

TOM: It’s created another one of those differences that need to be resolved before we—

ANN: Can claim our families.

TOM: We and the Muslims. They’re God’s children too.

ALEXANDER: An’ tha’s w’y I’m goin’ back tuh Cape Town?

TOM: Yes.

ALEXANDER: There’s anoother ma’er needs resolvin’, by th’ way. Has tuh do with you.

TOM: My turn, is it?

ALEXANDER: Yer task is easier. Won’ take yuh nearly so far.

TOM: What is it?

ALEXANDER: You go’ tuh persuade yer father, Sylvanus, tuh return tuh Provo an’ meet his jurors.

TOM: Revisit his trial?

ALEXANDER: Yes.

TOM: Why?

ANN: If I understand what’s expected of all of us now, then it’s also for me and my husband, your grandfather and namesake—Tom Karren. And all of our descendants too. If Sylvanus would just come clean about those murders, my Tom Karren could accept him again as one of the family. And he and his family, including you, our grandson, and all your offspring.

ALEXANDER: Looks like tha’ needs tuh happen too. So we kin all rejoin our looved ones…

TOM: How should I put it to him?

ANN: It’s already been said.

TOM: What do you mean?

ANN: (nodding toward Sylvanus) Tommy, don’t you know your own father? There he sits, and he’s taken in everything we just said.

SYLVANUS: (suddenly shouting) All of you—now freeze!

ANN: Come on, Sylvanus. What’s this always playing the desperado? You can’t threaten us.

ALEXANDER: (in a whisper) Shh, Sister Annie. I see it.

ANN: See what, Alexander?

ALEXANDER: (still whispering) That Diamond Back. Boost two fee’ froom where yur si’in’.

ANN: (also whispering) Oh…He’s a long one too…

(The sound of rattles. Sylvanus stalks toward the others then crouches and, slowly waving his hands, suddenly grasps an invisible snake.)

ALEXANDER: Yuh got ‘im. An’ joost look a’ ‘im twist an’ twine ‘bou’ yer arm.

ANN: How’d you dare do it?

SYLVANUS: Can’t harm us, so long as I keep grippin’ him like this behind that hateful skull. Now git me a flat rock, someone…

ANN: (handing him an invisible rock) Here.

ALEXANDER: No!

ANN: No, what?

ALEXANDER: Don’ touch ‘im!

SYLVANUS: Why not?

ALEXANDER: Remember wha’ muh gran’soon said ‘boo’ th’ ‘skee’ers? They kin’ do us noo Moore ‘arm. An’ remember Jooseph Smith at Zion’s Camp? We muoo’ not kill this one either.

SYLVANUS: Just had me a fish a while ago.

ALEXANDER: But no’ ou’ a’ meanness, or ’cause yuh feared it…Lemme look a’ ‘im—a’ his eyes. I know soomethin’ ‘boo’ these cri’ers…(drawing close to Sylvanus’s arm) Yes, yuh devil. I see yuh. An’ I see yer spirit…(to Sylvanus) Give ‘im tun me now…(appearing to take the snake from Sylvanus and bringing it close to his own face) Yuh may not like me, mister, but I ain’ afraid o’ you. Not anymoore. I’m resurrected, see. An’ that makes yuh helpless. Yer fangs cannot reach me, see…? Wanna handle ‘im, Sister Annie?

ANN: I’d say you’re doing just fine without my help.

ALEXANDER: (to the snake) Then go…go yer own way, mister. We’ll leave yuh tuh th’ Loord now…(He appears to release the snake.)

(Turning in the same direction, all watch the snake crawl away.)

ANN: Praise God…! And how are you, Sylvanus? Didn’t recognize you at first either.

SYLVANUS: Never thought they’d pursue me beyond the grave—and now my very own. All I ever did was for the Kingdom when I protected the Saints with drawn weapons. And when I married each of my wives.

ANN: When that Aiken party came along, poor boy, you were only twenty-one. Like Tommy here the last time I saw him. But tell us, love. We need to know—have you more to say than you told them at the trial?

SYLVANUS: So you doubt me too? Like all the others?

ANN: You need to reassure us. Particularly your own Tommy. And my Tom Karren.

ALEXANDER: Yuh go’ tuh face ‘em agin—th’ folks what witnessed agin’ yuh at th’ trial in Provo. Those are th’ instructions.

SYLVANUS: Another trial?

ALEXANDER: (reading from his papers) The same trial, says here.

SYLVANUS: Why should I?

ANN: Why, Syl, do you think you were raised up two days ago and directed here?

SYLVANUS: Can’t say.

ANN: We prayed you here, that’s why. And the Lord wanted you here too, or you’d still be laid out in the Cokeville cemetery.

SYLVANUS: Think so?

ALEXANDER: Lookee here. Do yuh care a’ all’ aboo’ yer…our wives an’ kiddies? Muh girl Kate an’ all th’ oothers whoo’ve coom aloong since then? Look where I gotta go talk tuh some infidels. Flyin’ there like a bird withou’ muh own wings. If I kin do tha’, you kin go back tuh Provo.

ANN: Tommy, may I join Alexander?

TOM: You really want to, Gramma?

ANN: Something tells me I ought to. It’s better than just tending my garden all day or flouring my hands in the kitchen while we wait for others to get their head and heart together.

TOM: I’ll need to check with…the Dispatcher.

ANN: How?

TOM: (producing a cordless phone) I’ll just punch a few numbers. Our discussion’s already been recorded. We’ll get an answer shortly.

ALEXANDER: Well, Sylvanus, how ‘bout it…?

SYLVANUS: You corralled me. An’, sure, I wanna see my kin again—all of ’em. If I really thought any of this would make that possible. Just hold off on all your questions.

ANN: Alright, love.

TOM: Thanks, Father. You can stay on my train all the way to Provo. (His phone beeps. He places it to his ear.) Yes…? Thank you, Brother.

ANN: What did he say, love?

TOM: I’ll make you up another ticket, Grandma…(He hands her a sheaf of documents.)

ANN: What’s that?

TOM: History of the Malays. Mostly about their religion. You’re Alexander’s assistant now, and you’re supposed to read up on it.

ANN: That’s something I’ve never thought about. Time I did, I guess. Isn’t eternity wonderful? There’s no end to it—or what we still have to learn about practically everything.

ALEXANDER: I feel a sudden chill.

ANN: Are you taking sick, love?

ALEXANDER: No. I’m troobled. No’ ’boot tha’ flyin’ contraption either. It’s wha’ cooms after—them pagan heathen we have tuh deal with.

TOM: That’s another reason you’re being sent there.

ALEXANDER: W’a’s tha’?

TOM: Your experience…with the spirits.

ALEXANDER: Though’ so.

TOM: Just be as fearless as you were with that rattler.

ALEXANDER: Tha’s th’ thing, laddie. I fear they’ll be serpen’s of a differn’ soort—changed in their shape boo’ still doin’ immense harm.

ANN: Now I know why I’m supposed to come with you, love. You’ll need someone by your side.

ALEXANDER: Aye, tha’ I will…I’m curious aboo’ a certain point though.

ANN: What would that be, Brother Alexander?

ALEXANDER: Wha’ made yuh soo a’venturous?

ANN: Well, besides all the moves we made and all the children we had—I lost quite a few more while still in the womb—which was always a great sorrow—just before we left Liverpool, our first child took ill, little Joseph. Our trunks were already stowed in the ship, and each morning for an entire week we’d have to go to the harbor to see if that was the day we’d sail. The very last night, Joseph passed away. I had to give him up for burial to my sister, who hadn’t spoken to me since we’d made ourselves Mormons…(She turns toward the auditorium, focusing on someone just in front of her, and extends her arms, as if holding a small bundle.) Thanks for coming, Mavis.

WOMAN’S VOICE: I can’t believe this.

ANN: I’m very grateful.

WOMAN’S VOICE: Grateful for what? That you’re finally rid of this one?

ANN: No. Please.

WOMAN’S VOICE: You have no heart. Or you’d never leave the poor thing like this.

ANN: There won’t be time. We sail at dawn. And my heart is broken, believe me. I know you’ll give him a decent burial.

WOMAN’S VOICE: With his mother already far gone? How do you think that will make him…his spirit feel?

ANN: He’ll understand.

WOMAN’S VOICE: And what will people say? The neighbors?

ANN: They’ll call you a saint.

WOMAN’S VOICE: And you something far different.

ANN: I can’t let people’s opinions decide what’s important.

WOMAN’S VOICE: Like those charlatan elders?

ANN: Mavis, I refuse to argue. As you well know, after my Tom Karren heard that missionary apostle John Taylor preaching on a street corner here in Liverpool, our purpose in life changed. WOMAN’S VOICE: Terribly.

ANN: No, wonderfully—for us and for our future family…. But thanks. Thanks for burying our boy.

WOMAN’S VOICE: Someone has to, that’s for sure.

ANN: And, Mavis, I’ll always love and pray for you.

WOMAN’S VOICE: No, I’ll pray for you.

ANN: (handing over her bundle) That’s good, Mavis. I hope you will. Goodbye. (turning to Alexander) We couldn’t dwell on it, me and Tom Karren. We had to move on. And with faith, we always did. I guess that’s your answer.

ALEXANDER: Sister Annie, yur a woonder! An’ how ‘bou’ you, Thomas? How many chil’ren di’ muh Kate give you??

TOM: We had two girls and a boy.

ALEXANDER: Three only? Wha’s this worl’ coomin’ to…?

TOM: We’ll miss the train to Salt Lake if we don’t soon head for Montpelier.

ALEXANDER: Aye, lad.

ANN: And then that flying machine.

TOM: Are you still with us, Father…?

SYLVANUS: Whatever else these people may think, son, I’m a man of my word.

TOM: (lightly touching his shoulder) Thank you, Father.

ANN: Bless you, Sylvanus. So where will you be then where we are gone?

SYLVANUS: Revisiting my 1878 trial in Provo.

TOM; And for what purpose, Father?…

SYLVANUS: Just like the rest of you, so that I can reclaim my family.

ALEXANDER: And ‘ow do we do that, laddie?

SYLVANUS: By confessing our sins and repenting.

ANN: And are you up to it this time?

SYLVANUS: Only if they prove to me I’m guilty…

ANN: You’ll be honest won’t you?

SYLVANUS: Yes.

ANN: And be guided by the Spirit?

SYLVANUS: Of course…

ANN: Then I only have this much more to say: I’ve heard some of you tell your stories, and I’ve told you mine. We’ve all had difficult choices to make in life, but we’ve made them. One of the reasons has to be our very own parents—like my saintly mother in Liverpool and my father, the baker there, even though they never knew about our church. And like my Thomas Karren’s parents on the Isle of Man. Hopefully, he and I have been a good example to you, Tommy. Your father Sylvanus too. And his parents to him. I understand that his father Daniel was a bodyguard to Joseph Smith in Nauvoo. And your parents, Alexander, back in Aberdeen. And surely your daughter Kate, my Tommy’s wife, and Tommy too.

TOM: We tried, Grandma.

ANN: I’m sure you did, Tommy…All good, honest, God-fearing people. All, as I can best tell, who modeled their lives after the Savior. That is what has made us want to do the same thing. And He will guide and be there with us. But we must also believe it and let nothing shake our faith in Him…

(The lights dim.)

CAMPFIRE

“But, Earl, unlike the Irish, the Scottish have a reputation for not being very talkative.”

“This one is, Jerry.”

“You’re sure?”

“It’s a play, Jerry.”

“Yes, I know. But he’s our forebear—a real person. Shouldn’t you at least try to approximate how he most likely was? And Sylvanus—he never wrote a single word about himself. No one ever quoted him either. For all we know, he was a deaf-mute.”

“Well, that’s equally unlikely. Now don’t get so restless, Jerry. What I’ve written serves a purpose.”

“Some dark Jesuitical purpose, I imagine.”

“Come on, Jerry. When we get to the trial, it’ll be the real thing. Right from the Tribune transcript.”

“And when will that show up?”

“You’ll see…”

RITES OF PASSAGE—THE YOUNG SYLVANUS

Benbow Farm, Herefordshire, England—1840

He holds our gaze, this American preacher. Thomas Oakey was our preacher till now. But this big boned man with the long shock of hair that keeps fallin’ down his face has persuaded Uncle Thomas he’s got far more for us than we’d known before, and just a month ago Uncle Thomas declared to us he didn’t have the right to preach no more—the right from God. That was a sign, he says, and God took notice. The big man, Woodruff, has restored that right to him and everyone’s pleased. The baptism was something else—took three full days. I wanted to get in the pond too, and kept trying to, but they said I was still too young. Some said I was showin’ off and just wanted a dip to get cool. That wasn’t it at all—I wanted the meanness taken out of me. How many times have Momma and Daddy told me I was plain mean and stubborn? Then I need a baptism as much as they do, maybe more. Just have to wait, I guess, till we get to America. We’re all going there with the big preacher—all of us United Brethren. Maybe they’ll dunk me after we get to Nauvoo.

Nauvoo—1843

I’m dunked at last! An’ not by Apostle Woodruff but by my own daddy. That was even better. But my thoughts were somewhere else—on what happened just before. This mornin’ another of them Gentile snoops came by—to gawk an’ mock, Momma says—and challenged the Prophet Joseph to a wrastle. He didn’t know that Brother Joseph is the best wrastler around. Never loses. But the Prophet had already wrastled at least two other men that same day, and, naturally, he was wore down. He’s just another mortal man like the rest of us, as he keeps remindin’ us. So Daddy doffed his cap an’ stepped up to the Prophet an’ offered to wrastle that man for him, an’ the Prophet agreed. Daddy’s a lot stronger than he looks. Bein’ a wheelwright and bodyguard to the Prophet keeps him in top shape. So he whipped that Gentile fast and clean. The man they call Port—his real name’s Rockwell—was standin’ right next to me. He’s a fierce looker with his gnarly hair way down to his shoulders, but he’s known the Prophet since the very beginning—one of the earliest members. And the Prophet counts on his pertection like none other. When Daddy was through with that Gentile man, Port turned to me and said, “You got a great dad there, son. He’s a credit to the Church and all o’ us.” I hope I can grow up and be as strong and nimble as Daddy and as trusted as both he and Port. I want to pertect the Prophet like they do an’ defend the Saints when they need it.

SAMUEL PITCHFORTH DIARY

Salt Creek (Nephi)—July 24, 1857

Quite pleasant in the forenoon but rather windy later. Had a first rate time. At daybreak music by Capt. Sperry’s band and firing of musketry at 9 a.m. The Escort was formed and marched through the principal streets in the following order: front Guard; Sperry’s band; twelve old men with flag, motto Fathers of Israel; twelve old ladies with banner, Mothers of Israel; Bishop Bigler and counselors; committee of arrangements; twelve young married ladies, banner Zion Shall Increase; twelve young men, banner Zion’s Defense; The Young Lions that were seen in the vision; 24 little boys with paper caps, banner Hope of Israel; 24 little girls, banner Israel’s Hope of Perpetuation—We Will Do It; rear Guard. All under the command of John Kinke, Marshall of the day. We then marched to the bowery which had been prepared for the occasion, where we heard an address by Brother Love. There was then permission given for anyone to speak that felt like it and for toasts, etc., which took up the forenoon. Then adjourned for two hours to partake of refreshments in companies of ten. The greater part of the afternoon was taken up in speaking, singing, music, reading, toasts, etc., after which there was a short time spent in dancing, then we adjourned for one hour after which we again assembled and spent the evening until 11 o’clock in dancing…Rockwell has brought news of a U.S. Army expedition being sent our way. Mention was made of Apostle Parley P. Pratt’s assassination, and Apostle Orson Hyde has been telling the Authorities of Sanpete to cut the neck of those who will keep doing wrong. Bishop Bigler was elected Captain of the first fifty of the Juab Battalion and John Kienke Captain of the first ten. John D. Lee declared that those members who back in Missouri and Illinois committed inexcusable acts of lawlessness and stole simply for the love of it were never really converted and not true Saints. Brigham Young disapproved of the cutting of young Lewis at Fort Ephraim for committing rape. He can never have an increase, and Brother Brigham pronounced his punishment too severe. Yesterday I worked at making a cradle to cut my wheat with and commenced cutting my wheat in the south field. My boy Joseph and my adopted son Lehi helped me. Lehi is a good worker, quiet and loyal. He remains grateful that I rescued him and will make a good Mormon—a future blessing to his people. He is learning our language at a quick pace—very bright and able. A joyful addition to our household.

HYMN SING

Church House, Salt Creek—Summer, 1857

O ye mountains high, where the clear blue sky

Arches over the vales of the free.

When the pure breezes blow and the clear streamlets flow,

How I’ve longed to your bosom to flee!

O Zion! dear Zion! land of the free,

Now my own mountain home, unto thee I have come.

All my’ fond hopes are centered in thee.

Tho the great and the wise all thy beauties despise,

To the humble and pure thou art dear;

Tho the haughty may smile and the wicked revile,

Yet we love thy glad tidings to hear.

O Zion! dear Zion! home of the free,

Tho thou wert forced to fly to thy chambers on high,

Yet we’ll share joy and sorrow with thee.

In thy mountain retreat, God will strengthen thy feet.

On the necks of thy foes thou shalt tread;

And their silver and gold, as the prophets have told,

Shall be brought to adorn thy fair head.

O Zion! dear Zion! home of the free,

Soon thy towers shall shine with a splendor divine,

And eternal thy glory shall be.

Here our voices we’ll raise, and we’ll sing to thy praise,

Sacred home of the prophets of God,

Thy deliverance is nigh; thy oppressors shall die;

And the Gentiles shall bow ’neath Thy rod.

O Zion! dear Zion! land of the free,

In thy temples we’ll bend; all thy rights we’ll defend;

And our home shall be ever with thee.

SAMUEL PITCHFORTH DIARY

Salt Creek—August 1857

Yesterday I finished cutting my oats. Lehi raked and bound for me. An express came from the City ordering us to secure our grain as fast as possible and drop every other kind of business. We are to thresh and save every grain and use it sparingly, eat vegetables, etc., where we can, and look out for places of safety in the mountains for our wives and children and to cache our grain, etc., if needs be. We must also make the Indians our friends, for the U.S. will soon be their enemies as they already are to the Sioux. Mr. T. B. Foote was elected mayor…Bishop Bigler’s brother-in-law, Apostle George A. Smith, preached this evening on his way home from Iron County. The authorities are alarmed about the impending invasion, while a company of Gentiles has already destroyed a supply of winter feed. Brigham Young has announced a scorched earth policy and President Wells has issued a letter urging the Saints to prepare to defend their wives and children from the army now approaching. We were reminded of Sidney Rigdon’s Salt Speech during the troubles in Missouri: This is a war of extermination, for we will follow them till the last drop of their blood is spilled, or they will have to exterminate us. Bishop Bigler asked those who would rather have their right arms severed from their body than back out of defending these people to raise those same hands. I think all hands were raised.

LETTER FROM JOHN AIKEN

Genoa, Carson Valley, Nevada—October 1857

Dear Nell:

You didn’t expect this letter, I’m sure—maybe you didn’t even expect to hear from me ever again. But since I was with you three weeks ago, my life has changed a good 180 degrees. Let me explain. When I was with you in Frisco, in that place, I was practically as new to it all as, from what you told me, so were you. To be really honest, Nell, I hated that place and I hate what it is doing to you. A different man every night, and probably more than one. My heart breaks for you when I think about it. I’m not judging you. You told me you were desperate—that you and your younger brothers and sisters were orphans now and you were doing it for them. Believe me, I admire you for that, Nell. It just shows how good you are at heart and how much you’ll do for others. But I also want to see you have a better life before it’s too late, and, yes, I feel partly responsible.

One reason—let me tell you frankly—is that after that night with you I, well, I just plain fell for you. I fell hard—harder than for anyone else in my entire life. And I want you to know that it was about the first time for me when I was with you. In fact, there was just one other time—when I turned fourteen and my brother Tom took me to one of those places down in L.A. I only went there then because he made me in order to prove I was a man. I didn’t like it then, especially afterward. And I didn’t like it when Tom and his friends took me to your place three weeks ago. Please understand me, Nell. I liked you, liked you a lot. But not what I did to you, not after it was over because, like that one time before, it just wasn’t the way such things should be done. Things like that need to be permanent and bonding, not just some fly-by-night commercial exchange.

Now let me tell you why I especially feel this way right now—what’s happened since Tom and I and the others headed east. We met up with some folks—we’re with them right now here in the town Lehi—and they’ve opened my eyes to what’s really important, what really brings lasting happiness. And I want them to open your eyes too, Nell. Because…because—please believe me—I love you. I do, Nell—with all my heart—and it makes me so happy. Oh, how I miss you, Nell.

Now this is what really changed me. Please listen. Please keep an open mind. Remember how you cried on my shoulder after we…You were so sweet, so tender, and you just melted me right then and there. I wanted so bad to protect you then and I want to now—forever, Nell, forever. And forever is a long time, but as there is a God in Heaven, Nell, He wants us to have that blessing—happiness forever as loving, committed husbands and wives. I learned this from these good people we’re with who are on the move with us and have kindly offered to provision us and give us an escort.

Who are they, you’re asking? Well, this is who: they’re the settlers here in Carson Valley, called back to Utah just now. Yes, they’re the Mormons. Maybe you’ve never even heard of Mormons. I’m not sure I had either. They’re very God-fearing, Nell. And they’ve been persecuted for it too. Chased, they tell me, first from New York state, then to Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois—across the entire country. But you should see them and their beautiful families—their sweet, innocent children. At night their families pray together and again in the morning. And they work together, help each other out, and take care of their sick and poor. The men—they’re all priests and preachers, righteous heads of their families, empowered to bless them. They strive to rise above the natural man in them, and that’s why they’re really what they call themselves—Saints, Saints of the Latter Days…