Throughout the United States, recent high school graduates and college students delay or take breaks in their higher education for a variety of reasons. These reasons include employment (e.g., to save money for college), personal illness or caring for loved ones, military service, religious missionary service, or experiential learning outside the classroom. Taking a break from college also happens in Utah, as evidenced by the 30.9% of Utah freshmen students who do not reenroll for their second fall semester. [1]

The disruptions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic only increased the phenomenon of non-linear progression through higher education in the US, and Utah was no exception. Enrollment at higher education institutions in Utah fell 1.9% between Fall 2020 and Fall 2021. [2] Anecdotes about freshmen students delaying enrollment or older students taking a break during the pandemic also abounded. [3]

One common and increasingly popular reason for delaying or taking time away from school is a gap year, which the Gap Year Association defines as, “A semester or year of experiential learning, typically taken after high school and prior to career or post-secondary education, in order to deepen one’s practical, professional, and personal awareness.” [4] Under that definition, gap time is purposeful, structured, and can include service and experience with new places and cultures. Religious missionary service would then fit the definition of structured gap time, something that many Utah students participate in because of membership in Utah’s dominant religion: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

With many students throughout the US and Utah experiencing interruptions in their post-secondary education, it is valuable to understand the consequences, both positive and negative. Structured and unstructured gap time look very different for students and tend toward different outcomes. On the one hand, structured gap time gives young adults opportunities to build skills and identify strengths and preferences. On the other hand, unstructured gap time is typically unplanned and linked to obstacles like health or financial problems. Since past research has shown that unstructured gap time leads to generally negative outcomes, [5] this brief focuses on the benefits and drawbacks of structured gap time.

Although women participate in structured gap time less often than men, [6] this may be shifting for Utah women due to changes in missionary service guidelines and decisions made during the COVID-19 pandemic. The potential benefits women receive by participating in structured gap experiences may help reduce gender differences in fields of study and career tracks. Alternatively, gap time may weaken ties to college, making it harder to progress in educational goals. This brief highlights findings from a study examining the impact of missionary service gap time on a sample of Utah students, with particular attention to the unique benefits and drawbacks for women.

Study Background

Our study used administrative student data from Brigham Young University (BYU) located in Provo, Utah. BYU is uniquely situated to provide insight into gap time in Utah. It is a private university sponsored by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and a high proportion of enrolled students choose to serve missions. In October 2012, [7] the Church made a change to its missionary policy, which allowed women to leave on missions at age 19 instead of age 21. Subsequently, an upsurge of female students chose to serve a mission. For the purposes of this study, we used administrative data from students who enrolled within the five-year period before this change and tracked their data through 2020 to give students at least eight years to graduate.

The data included demographic information and variables about academic timing, academic choices, and academic performance. Demographic information was used to compare BYU female students to other Utah and US female students. Then, using a larger analytic sample of BYU female students, we evaluated the impact of taking gap time for missionary service (or not) on choice of major, GPA, and graduation rates. The results are organized into three sections: 1) sample characteristics, 2) benefits of missionary gap time, and 3) drawbacks of missionary gap time. Findings are discussed in the context of Utah and national research and trends. We conclude by providing action and policy recommendations. Note: additional findings from this study were published as a peer-reviewed journal article in Education Finance & Policy. [8]

Sample Characteristics

The study sample consisted of female students who enrolled at BYU before the mission policy change, between Fall 2007 and Fall 2012. The reason we focused on this time period was because it allowed us to exploit the mission age policy change for women. The approach of comparing women just before and after the policy change allowed us to isolate and study the consequences of missionary service without confounding the personal characteristics of women. We then had to wait for nearly a decade before analyzing the women to give them adequate time to complete their undergraduate education. We excluded women from the sample who were over the age of 26 (the average age of BYU students during this period was 21.6) or were transfer students as these groups have unique higher education experiences. The final sample size for our study was 17,402 women, 29.1% of which took gap time to serve a full-time mission.

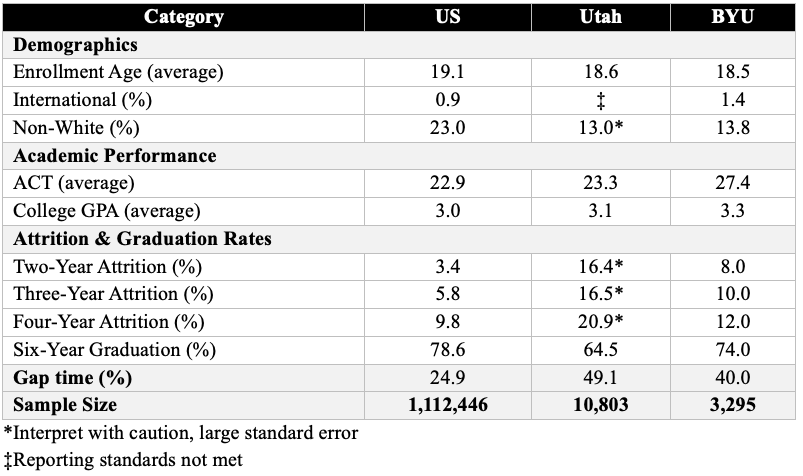

Although the context of a private, religious institution like BYU differs in some ways to other colleges and universities, we found that the descriptive characteristics of female BYU students were generally comparable to female students at other universities. We located Utah and overall US data about female students who enrolled 2011–2012 at bachelor’s degree granting public and non-profit private institutions. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics comparing data from Utah and US students to data from BYU students who also enrolled during that time frame.

The BYU subsample had higher ACT scores and fewer non-White students than other US universities. BYU’s attrition rates—meaning the cumulative percentage of students who leave permanently after each year of schooling—were more like other US universities, and lower than other Utah universities. The proportion of students graduating within 6 years was higher for BYU than other Utah universities and similar to US universities. Most notably, Utah (49.1%), not just BYU (40.0%), had a higher percent of female students who participated in gap time compared to US universities (24.9%), reiterating the importance of understanding the effect of gap time on Utah women.

Table 1: Demographic and Academic Outcomes for Female Students Initially Enrolled 2011-2012 [9]

Benefits of Missionary Gap Time

Gap time offers certain benefits and can change the course of a person’s life in positive ways. If this were not true, we would not see so many women choosing to participate in gap time experiences. Nonetheless, it is important to articulate and understand areas of benefit, which can be categorized as educational, professional, and personal.

Educational

In terms of educational benefits, research suggests some important benefits for women. First, in our study we found that many women change their majors after taking gap time for missionary service, and these majors often have more men and higher earning potential. Specifically, women who took gap time were 33.0% more likely to switch into a major with higher earning potential than women who did not take gap time. [10] Presumably, missionary gap time can help women learn about their preferences and abilities. Missionary service may also increase confidence for women, which is significant since past research has shown that women typically express lower confidence in their abilities than men. [11] Women also build new skills and determination through living in new places. With these new perspectives, a woman may feel empowered to choose a college major that is a better fit for her or one that opens new opportunities in the future.

Second, we found that gap time for missionary service seems to be particularly useful for women who struggle academically. [12] Missionary service is a way for these women to develop strengths that are not reflected in test scores or grades alone. As a result, missionary gap time seems to help women with less than perfect academic backgrounds (e.g., lower ACT scores) get accepted into competitive academic programs, like business schools. We found that among women with ACT scores in the lowest third, those who took gap time for missionary service were 19.0% more likely to be accepted into a competitive or limited enrollment program. [13]

Third, gap time for missionary service can help women be successful in school once the gap time concludes and women return to college. On average in our study, women who served missions earned GPAs that were 0.1 points higher than those who did not. [14] Although this statistically significant difference is small, other researchers have also found that structured gap time that involves travel relates to better academic outcomes for women after they return to college. [15] Other students returning to college after missionary gap time received higher grades and took more credits when they returned, likely due to increased maturity and work ethic. [16] Overall, there are important academic benefits of missionary gap time for women.

Professional

Gap time for missionary service offers valuable professional benefits to women following college, although less is known about this. What is known suggests that missionary gap time affects women’s professional opportunities through both tangible and intangible channels. Our research highlights a clear tangible benefit in terms of women often moving into majors with higher earning potential following missionary service. [17] This may better prepare women to secure financial stability later in life. While less tangible, missionary gap time may also help a woman signal to future employers that she has the inner ability to work well with people unlike her and take on new or undefined tasks. In competitive job markets, these experiences may set someone apart and give them an edge over peers. [18] Whether through tangible or intangible channels, gap time has clear benefits for a woman’s future earnings and long-term career trajectory.

Personal

Women appear to benefit personally from gap time for missionary service as well. When asked about missionary service experiences, women consistently reported that these experiences were personally valuable. Other researchers suggest that missionary gap time enlarges a woman’s view of the world, leading to increased racial and cultural acceptance. [19] Some students build language skills, which is particularly applicable in Utah with the number of women who serve religious missions in foreign languages. [20] Upon returning from missionary service, women observe that benefits of the experience included developing interpersonal relationship skills, courage, confidence, personal awareness, maturity, independence, and an increased ability to overcome challenges. [21]

Drawbacks of Missionary Gap Time

Women who take time away from higher education for structured gap experiences receive personal and professional growth and development, but the time away from school does not come without costs. The financial costs may be the most obvious. Individuals often pay to participate in missionary service and do not make money during the experience. Research about other gap time experiences found that 60% of gap time participants made no money during the experience, while 66% spent more than $5,000. [22] There is also an opportunity cost associated with gap time because participants delay completing education, entering the workforce, and other endeavors. Many women find that these costs are worth the benefits of broader cultural awareness, confidence, independence, and new relationships that are harder to obtain in a traditional classroom. [23]

There are also clear drawbacks that occur after completing gap time experiences. With time away from school, there is an increased risk that students will simply not return to college after completing a gap experience. [24] However, our research on female students at BYU suggests this may be a minimal concern in Utah. We found that 96.0% of women who took gap time for missions for the Church of Jesus Christ returned to college after time away from the university. [25] Just returning to school following gap time increases the chances of academic success, [26] which in turn influences employment opportunities and future income.

While returning to college following missionary service is important, it is not enough. Nor is it the end of the impacts of gap time on women’s higher education experience. Missionary service naturally delays graduation, which can also delay women beginning their careers. The graduation rate for women at BYU who took gap time to serve a religious mission lagged behind the non-gap time graduation rate by about 1.5 – 2 years. [27] The length of a mission for women is 1.5 years, so this suggests that some women completed college at the normal rate after gap time, while others were delayed by about a semester. This may be due to the timing of the mission, where some students return mid-semester and therefore must wait several months before re-enrolling.

Taking gap time for missionary service also decreased the chances of graduating from college at all. We found that women who took gap time for missions were 10.0% less likely to graduate in 8 years than their peers who did not serve missions, after adjusting for personal characteristics. [28] We found that women who returned from missionary service initially remain enrolled. At about four years after college enrollment, these women began to leave higher education without graduating. [29] We can only speculate reasons why this may be happening. It may be that some of these women are navigating a transition to parenthood or leaving campus with a spouse who is pursuing other opportunities. This is a significant difference in both statistical and practical terms. The timing suggests many of these women are approaching graduation, and could likely finish with more support and flexibility from the university.

Action & Policy Recommendations

Although missionary gap time leads to both positive and negative outcomes for women, there are actions that female students, their families, and university personnel can take to minimize the drawbacks and capitalize on the gains of gap experiences. We provide the following suggestions as a starting point for discussions about ways to help women progress and complete their degrees while taking advantage of gap time benefits, like increased confidence, soft skills, and interest in more lucrative fields. These recommendations should benefit students who take gap time for missionary service or other reasons.

First, young adult women interested in gap experiences should consider and weigh the potential costs and benefits that may come educationally, professionally, and personally. Parents and family members can encourage and assist in thoughtful decision-making around gap time participation. In this way, gap time experiences are like other major life choices that college-age adults face, which are best made after obtaining relevant information and comparing pros and cons. Universities should provide easily accessible information that details how gap time affects their academic programs and outcomes. For instance, Southern Utah University provided a decision-making guide about the pros and cons of gap time during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, before women start gap time experiences, and certainly as they complete gap time, they can make firm commitments to return to school. Students can plan ahead by looking at university deferment and return policies (see examples of Westminster College’s Deferred Enrollment and Gap Year webpage and Utah Valley University’s Leave of Absence webpage). When students are absent long enough that they need to apply for readmission, universities can ensure this process is clearly explained and offer support.

Third, family and university advisors can augment personal commitments by encouraging students to return and supporting them in the process. Advisors can play an intentional role in mitigating any barriers students may face upon returning such as reintegrating with university life, refreshing academic skills, learning about university policy changes, and registering for classes. Extracurricular student groups may also help returning students find similar peers and feel more belonging on campus.

Although women may readjust to university life quickly, there may be later factors that affect their college experience and graduation rates, such as being older than other students, health challenges, lack of support, getting married, and having children. [30] Given the increased likelihood that women who take gap time for missionary service may not graduate, university personnel need to continue supporting students beyond the initial semester or year after returning. We suggest that university advisors keep in contact with women who take gap time throughout the rest of their educational experience.

Additionally, as women who took gap time near internship opportunities and graduation, they would benefit from guidance on how to frame those experiences to their advantage on resumes and in program or job applications. For example, the BYU Careers and Experiential Learning team provides information and guidance for how religious mission experiences and skill building can be applied in future jobs.

Fourth, another way to support students returning from gap time is by providing scholarships and grants. A report from the Utah System of Higher Education (USHE) found that students who take gap time, referred to as “stopout” in their report, are more concerned about finances and more sensitive to the cost of higher education. [31] Utah universities and other scholarship-granting entities should explore implementing more funding opportunities for returning gap time students (e.g., Utah State University’s completion scholarship).

Fifth, students who take gap time may benefit from flexible academic options. One benefit of missionary gap time is how the gained experience helps women be successful in competitive majors, particularly for those with lower scores on traditional metrics like test scores. However, competitive programs often have yearly application deadlines. If a student misses the deadline due to gap time, it may further delay her academic progress to wait another year. To address this potential barrier, university programs should consider having a rolling application system or multiple deadlines throughout the year. The USHE report also found that the majority of students who experience gap time value customization in progressing through their degree. Flexible options—such as online courses—could help returning women complete a degree. For example, the University of Utah’s program, Return to the U, provides online, satellite, and short-term options. At BYU, returning students can choose to complete a Bachelor of General Studies, which can be done entirely from home.

Conclusion

Structured gap time experiences for full-time missionary service are increasingly common for women attending Utah colleges and universities. The presence of both costs and benefits creates a tension when considering the value of gap time experiences. We suggest that women carefully evaluate their own motivations, circumstances, and goals as they navigate that tension and make decisions about whether to take gap time for missionary service or other reasons. A clear message of past research is that costs and benefits differ across women. This implies that while understanding common patterns is helpful, blanket statements miss important nuances of each person’s situation. Each woman will have unique insight into how gap time may be beneficial as well as personalized strategies that can minimize any downsides.

Gap time experiences at a pivotal stage in life are exciting to consider for all college students. They have the potential to change a person’s life trajectory, understanding of themselves, and understanding of the world. Our study findings and recommendations will help individuals, families, and institutions of higher education understand the impact of gap experiences and offer appropriate support to Utah students as they face decisions about interrupting college and embarking on gap time experiences.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Dr. Emily S. Darowski and Dr. Susan R. Madsen for their coaching and reviews.

Originally published by: Utah Women & Leadership Project, February 2, 2023

NOTES:

[1] Utah System of Higher Education. (n.d.). USHE results. https://ushe.edu/data/ --- [Back to manuscript].

[2] National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2021). Fall 2021 enrollment #2 (10.21): 3. states, enrollment intensity, campus setting. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/researchcenter/viz/Fall2021Enrollment210_21/StayInformedFall2021 --- [Back to manuscript].

[3] West, C. (2020). Coronavirus fears may lead to big gap year for college students. PBS News Hour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/coronavirus-fears-may-lead-to-big-gap-year-for-college-students --- [Back to manuscript].

[4] Gap Year Association. (n.d.). About us. https://www.gapyearassociation.org/about-us/ --- [Back to manuscript].

[5] DesJardins, S. L., Ahlburg, D. A., & McCall, B. P. (2006). The effects of interrupted enrollment on graduation from college: Racial, income, and ability differences. Economics of Education Review, 25(6), 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.06.002; Fortin, B., & Ragued, S. (2017). Does temporary interruption in postsecondary education induce a wage penalty? Evidence from Canada. Economics of Education Review, 58, 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.04.001; Witteveen, D., & Attewell, P. (2021). Delayed time-to-degree and post-college earnings. Research in Higher Education, 62, 230–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09582-8 --- [Back to manuscript].

[6] Ewert, S. (2010). Male and female pathways through four-year colleges: Disruptions and sex stratifications in higher education. American Educational Research Journal, 47(4), 744–773. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210374351 --- [Back to manuscript].

[7] Monson, T. S. (2012, November 12). Welcome to conference. Ensign. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/2012/11/saturday-morning-session/welcome-to-conference?lang=eng --- [Back to manuscript].

[8] Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). College gap time and academic outcomes for women: Evidence from missionaries. Education Finance & Policy. https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00389 --- [Back to manuscript].

[9] Data for US and Utah come from National Center for Education Statistics Beginning Postsecondary Students Survey (2012–2017). https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/bps/. Data for BYU comes from university administrative records. [Back to manuscript].

[10] Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). p. 20. [Back to manuscript].

[11] Niederle, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2007). Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1067–1101. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1067; Pope, D. G. (2017, August 8). Women who are elite mathematicians are less likely than men to believe they’re elite mathematicians. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/08/08/women-who-are-elite-mathematicians-are-less-likely-than-men-to-believe-theyre-elite-mathematicians/ --- [Back to manuscript].

[12] Birch, E. R., & Miller, P. W. (2007). The characteristics of ‘gap-year’ students and their tertiary academic outcomes. Economic Record, 83(262), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2007.00418.x; Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). [Back to manuscript].

[13] Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). [Back to manuscript].

[14] Marchant, M, & Wikle, J. S. (2022). p. 42. [Back to manuscript].

[15] Birch, E. R., & Miller, P. W. (2007); Hoder, R. (2014, May 14). Why your high school senior should take a gap year. Time. http://time.com/97065/gap-year-college/; Stehlik, T. (2010). Mind the gap: School leaver aspirations and delayed pathways to further and higher education. Journal of Education and Work, 23(4), 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2010.492392; Tenser, L. I. (2015). Stepping off the conveyor belt: Gap year effects on the first-year college experience [Doctoral dissertation, Boston College]. eScholarship@BC. http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104364 --- [Back to manuscript].

[16] Pope, D. G. (2008). Benefits of bilingualism: Evidence from Mormon missionaries. Economics of Education Review, 27(2), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.09.006 --- [Back to manuscript].

[17] Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). [Back to manuscript].

[18] Heath, S. (2007). Widening the gap: Pre-university gap years and the ‘economy of experience.’ British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690600996717; King, A. (2011). Minding the gap? Young people’s accounts of taking a gap year as a form of identity work in higher education. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2010.522563; Simpson, K. (2005). Dropping out or signing up? The professionalisation of youth travel. Antipode, 37(3), 447–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0066-4812.2005.00506.x --- [Back to manuscript].

[19] Crawfurd, L. (2021). Contact and commitment to development: Evidence from quasi‐random missionary assignments. Kyklos, 74(1), 3–https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12255; Riess, J. (2019). The next Mormons: How millennials are changing the LDS Church. Oxford University Press; Smith, T. B., Roberts, R. N., & Kerr, B. (1996). On the cross-cultural attitudes and experiences of recently returned LDS missionaries. AMCAP Journal, 22(1), 119–133. http://hdl.lib.byu.edu/1877/2799 --- [Back to manuscript].

[20] Pope, D. G. (2008). [Back to manuscript].

[21] King, A. (2011); Madsen, S. R., Scribner, R., Kirk, W. F., & Lafkas, S. M. (2020, January 7). The leadership development gained by women serving full-time missions. Utah Women & Leadership Project. https://www.usu.edu/uwlp/files/briefs/21-leadership-development-full-time-missions.pdf; Riess, J. (2019). [Back to manuscript].

[22] Gallagher, N. H., & Blythe, K. (2020). Gap year alumni survey 2020. Gap Year Association. https://www.gapyearassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/2020-GYA-Survey-Report.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[23] Tenser, L. I. (2015). [Back to manuscript].

[24] Arcidiacono, P., Aucejo, E., Maurel, A., & Ransom, T. (2016). College attrition and the dynamics of information revelation. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 22325. https://doi.org/10.3386/w22325 --- [Back to manuscript].

[25] Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). p. 21. [Back to manuscript].

[26] Birch, E. R., & Miller, P. W. (2007). [Back to manuscript].

[27] Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). [Back to manuscript].

[28] Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). p. 21. [Back to manuscript].

[29] Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). p. 21. [Back to manuscript].

[30] Horn, L., Cataldi, E. F., & Sikora, A. (2005). Waiting to attend college: Undergraduates who delay their postsecondary enrollment (NCES 2005–152). US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2005/2005152.pdf; Utah System of Higher Education. (2021, July 16). Utah Board of Higher Education strategic plan. https://ushe.edu/wp-content/uploads/pdf/agendas/20210716/CoW-presentations_07-16-21.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[31] Utah System of Higher Education. (2021, July 16). [Back to manuscript].

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Arcidiacono, P., Aucejo, E., Maurel, A., & Ransom, T. (2016). College attrition and the dynamics of information revelation. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 22325. https://doi.org/10.3386/w22325

Birch, E. R., & Miller, P. W. (2007). The characteristics of ‘gap-year’ students and their tertiary academic outcomes. Economic Record, 83(262), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2007.00418.x

Crawfurd, L. (2021). Contact and commitment to development: Evidence from quasi‐random missionary assignments. Kyklos, 74(1), 3–https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12255

DesJardins, S. L., Ahlburg, D. A., & McCall, B. P. (2006). The effects of interrupted enrollment on graduation from college: Racial, income, and ability differences. Economics of Education Review, 25(6), 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.06.002

Ewert, S. (2010). Male and female pathways through four-year colleges: Disruptions and sex stratifications in higher education. American Educational Research Journal, 47(4), 744–773. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210374351

Fortin, B., & Ragued, S. (2017). Does temporary interruption in postsecondary education induce a wage penalty? Evidence from Canada. Economics of Education Review, 58, 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.04.001

Gallagher, N. H., & Blythe, K. (2020). Gap year alumni survey 2020. Gap Year Association. https://www.gapyearassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/2020-GYA-Survey-Report.pdf

Gap Year Association. (n.d.). About us. https://www.gapyearassociation.org/about-us/

Heath, S. (2007). Widening the gap: Pre-university gap years and the ‘economy of experience.’ British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690600996717

Hoder, R. (2014, May 14). Why your high school senior should take a gap year. Time. http://time.com/97065/gap-year-college/

Horn, L., Cataldi, E. F., & Sikora, A. (2005). Waiting to attend college: Undergraduates who delay their postsecondary enrollment (NCES 2005–152). US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2005/2005152.pdf

King, A. (2011). Minding the gap? Young people’s accounts of taking a gap year as a form of identity work in higher education. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2010.522563

Madsen, S. R., Scribner, R., Kirk, W. F., & Lafkas, S. M. (2020, January 7). The leadership development gained by women serving full-time missions. Utah Women & Leadership Project. https://www.usu.edu/uwlp/files/briefs/21-leadership-development-full-time-missions.pdf

Marchant, M., & Wikle, J. S. (2022). College gap time and academic outcomes for women: Evidence from missionaries. Education Finance & Policy. https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00389

Monson, T. S. (2012, November 12). Welcome to conference. Ensign. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/2012/11/saturday-morning-session/welcome-to-conference?lang=eng

National Center for Education Statistics Beginning Postsecondary Students Survey (2012–2017). https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/bps/

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2021). Fall 2021 enrollment #2 (10.21): 3. states, enrollment intensity, campus setting. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/researchcenter/viz/Fall2021Enrollment210_21/StayInformedFall2021

Niederle, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2007). Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1067–1101. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1067

Pope, D. G. (2008). Benefits of bilingualism: Evidence from Mormon missionaries. Economics of Education Review, 27(2), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.09.006

Pope, D. G. (2017, August 8). Women who are elite mathematicians are less likely than men to believe they’re elite mathematicians. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/08/08/women-who-are-elite-mathematicians-are-less-likely-than-men-to-believe-theyre-elite-mathematicians/

Riess, J. (2019). The next Mormons: How millennials are changing the LDS Church. Oxford University Press

Simpson, K. (2005). Dropping out or signing up? The professionalisation of youth travel. Antipode, 37(3), 447–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0066-4812.2005.00506.x

Smith, T. B., Roberts, R. N., & Kerr, B. (1996). On the cross-cultural attitudes and experiences of recently returned LDS missionaries. AMCAP Journal, 22(1), 119–133. http://hdl.lib.byu.edu/1877/2799

Stehlik, T. (2010). Mind the gap: School leaver aspirations and delayed pathways to further and higher education. Journal of Education and Work, 23(4), 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2010.492392

Tenser, L. I. (2015). Stepping off the conveyor belt: Gap year effects on the first-year college experience [Doctoral dissertation, Boston College]. eScholarship@BC. http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104364

Utah System of Higher Education. (2021, July 16). Utah Board of Higher Education strategic plan. https://ushe.edu/wp-content/uploads/pdf/agendas/20210716/CoW-presentations_07-16-21.pdf

Utah System of Higher Education. (n.d.). USHE results. https://ushe.edu/data/

West, C. (2020). Coronavirus fears may lead to big gap year for college students. PBS News Hour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/coronavirus-fears-may-lead-to-big-gap-year-for-college-students

Witteveen, D., & Attewell, P. (2021). Delayed time-to-degree and post-college earnings. Research in Higher Education, 62, 230–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09582-8

![]()

Full Citation for this Article: Maggie Marchant & Jocelyn Wikle (2023) "Impact of Gap Time for Missionary Service on Utah Women’s College Outcomes," SquareTwo, Vol. 16 No. 2 (Summer 2023), http://squaretwo.org/Sq2ArticleMarchantWilkeWomensCollege.html, accessed <give access date>.

![]() Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome.

Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome.