Sexism takes many forms, from blatant and aggressive to unintentional and subtle. Gender-related societal attitudes, social norms, unconscious biases, and microaggressions all contribute to the sexist behaviors and attitudes that are partially responsible for much of the inequity women face every day in a variety of settings. Researchers have noted that “in both private and public spaces, women encounter messages that reinforce gender roles and stereotypes, demean women as a gender group, and sexually objectify women.” [1] Sexist comments and remarks show up in everyday conversations, public discourse, and virtually every other social setting—including in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

As sexist comments are pervasive, and appropriate responses elusive, the Utah Women & Leadership Project (UWLP) conducted a research study that was designed with the intent of collecting and analyzing a wide variety of sexist comments experienced by women across the state of Utah, in addition to the responses women made (or wish they would have made) to such comments. The goal of this study was to educate the public on the many forms of conscious and unconscious sexist comments made by individuals (both men and women), and to equip women with effective responses that could reduce sexism in all settings. In addition to five research and policy briefs already released on this study, [2] we wanted to pull out the data specific to Latter-day Saint contexts and share it separately in this article. Hence, the goal of this piece is to educate members of the Church on the many forms of conscious and unconscious sexist comments made in Church settings.

Although many Latter-day Saint women experience sexism within the Church in various forms, the doctrines taught do not condone such actions or occurrences. For example, common Church teachings include becoming less judgmental and increasing in love, charity, and respect for all. Further, for years leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have emphasized the importance of men and women working together. Latter-day Saints are taught that “Men and women have different but equally valued roles.” [3] In his book Counseling with Our Councils, Elder M. Russell Ballard stated, “It is only when both perspectives come together that the picture is balanced and complete. Men and women are equally valuable in the ongoing work of the gospel kingdom.” [4] President Russell M. Nelson shared similar sentiments: “I plead with my sisters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to step forward! Take your rightful and needful place in your home, in your community, and in the kingdom of God—more than you ever have before.” [5] And yet, despite statements from Church leadership reinforcing women’s valued status within the Church, sexist comments and attitudes persist in Church settings. As author Neylan McBaine stated in her book Women at Church, “Women in the Church today can feel a tension between what they are being taught at church or how they’re being engaged at church, and what they feel is a true evaluation of their potential and worth.” [6] Sexism is a cultural construct.

This article will begin with highlighting key definitions and then will provide research background and demographic information about the study participants. We will then report findings and offer concluding remarks.

Definitions

Sexism refers to “prejudice or discrimination based on sex” and “behavior, conditions, or attitudes that foster stereotypes of social roles based on sex.” [7] Although it can take many forms, such as words or actions from men to women, women toward men, and even women toward women and men toward men, the most common form continues to be from men to women. The literature breaks sexism into two categories: hostile and benevolent.

Hostile sexism is usually easy to spot and, according to researchers, [8] this type of sexism includes more blatant prejudiced attitudes and obvious negative stereotypes, assessments, or evaluations about a gender. For example, this can include statements and actions that generalize women as inferior to men, not competent, unintelligent, too emotional, and manipulative. Sexual harassment fits into this category too. Examples can include the following situations: telling or laughing at sexist jokes; deciding on a hire, promotion, or pay increase based on gender; calling on only male employees to make comments in meetings; or regularly asking women (who are in the same positions as men in a meeting) to be the ones to get drinks or take notes. [9]

Benevolent sexism is more subtle and often comes from individuals thinking they have the best of intentions. However, it includes “subjectively positive attitudes of gender that can actually be damaging to individuals (particularly women) and to gender equality more generally. Most of the time the language or actions are subtle, unconscious, and habitual.” [10] With this type of sexism, there is an underlying assumption that women’s inherent differences dictate that they should be limited to certain roles and tasks and need assistance or protection. For example, failing to give women specific assignments in any setting (e.g., workplace, community board, or church assignment) because it might be “too stressful” or interfere with her family commitments is a common situation, particularly in the Church. Another would be when people focus, even positively, on a woman’s appearance; while this may be well-intentioned, it can undermine a women’s feeling of being taken seriously. Benevolent sexism also takes the form of putting women on a “pedestal.” In the Church we see this often (e.g., my “angel mother,” or women being seen as the paragons of virtue or spirituality). When women are idealized it can feel both condescending and paralyzing at the same time—there is the sense that women are being placated, but also the hopeless feeling that comes from knowing it is impossible to live up to the perfect ideal. Finally, when people acknowledge women only when they fit the norms (e.g., nurturing, compassionate, intuitive, empathetic)—even when they have other positive qualities that are more often valued in public settings (e.g., results-oriented, strategic, assertive, professional)—this is also a form of benevolent sexism. The bottom-line is that even though benevolent sexism can appear on the surface to be positive, it can still undermine and hurt individuals.

Study Background & Demographics

From May-June of 2020, an online survey instrument was administered to a nonprobability sample of Utah women representing different settings, backgrounds, and situations (e.g., age, marital status, education, race/ethnicity, parenthood status, employment status, faith tradition, and county/region). This research study was designed with the intent of collecting and analyzing a wide variety of sexist comments experienced by women across the state of Utah. A call for participants was announced through the Utah Women & Leadership Project (UWLP) monthly newsletter, social media platforms, and website. [11] UWLP partners, collaborators, and followers also distributed in their circles of influence. Overall, 1,115 participants started the survey, and 839 Utah women completed enough for their responses to be usable in the study. Each participant was allowed to share up to four comments, and 1,750 individual comments were reported. Of these 1,750 comments, 119 individual comments, reported by 99 survey participants, occurred in a religious context. The research presented in this paper focuses solely on those 119 responses. Research from the full study on Sexist Comments & Responses can be found on the Utah Women & Leadership Project website (www.utwomen.org).

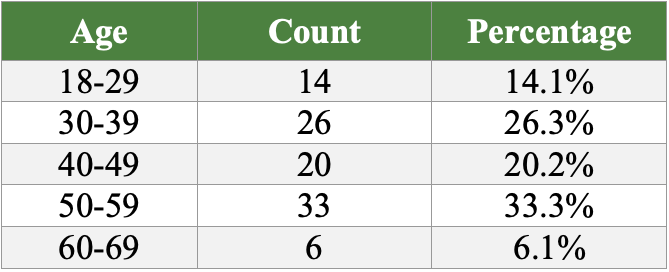

Of the 99 survey participants who shared comments made in their religious contexts, 85 (85.9%) identified as members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 11 (11.1%) identified as “No Religion,” and 3 (3.0%) identified as “Other Religion.” Of these 14 participants who identified with “No Religion” or “Other Religion,” 11 of them had sexist remarks made to them from a member of the Latter-day Saint Church. Although the remaining three did not specify the religion of the “offender,” the comments reflect cultural beliefs that are often held by members of the Church (such as “Women are suited for nurses, teachers, and motherhood. Let’s not distract from where God-given talents reside”). Hence, we chose to include these comments in the analysis for this article though it is important for the reader to keep in mind that we cannot be certain these three comments were made by members of the Latter-day Saint Church. Although these three comments could be statements made in other religious settings within the state of Utah, an estimated 60.68% of the population identifies as members of the Latter-day Saint Church. [12] Even so, this limitation should be kept in mind by the reader. Also, it is important to note that only Utahns participated in this research, so this is a report focused on sexist comments by members of the Church who live within the state of Utah. See Table 1 for a breakdown of the ages of the women who participated in the study and mentioned comments made in their religious contexts.

Table 1: Participant Ages (All Women)

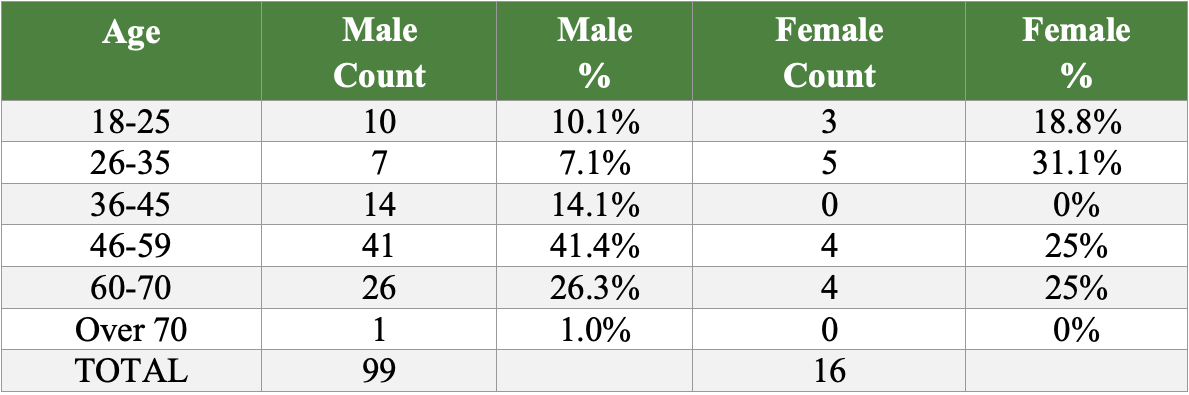

Of the 119 accounts of sexist remarks or actions, 99 were made by men (83.2%), 16 were made by women (13.4%), and 4 were not specified (3.4%). Curiously, while most of the remarks made by men came from men ages 46-70 (67.7%), the sexist remarks made by women were spread relatively evenly among ages 18-70 (see Table 2 for the ages of the commenters by gender).

Table 2: Ages of Commenters

Male Commentors=83.2%

Female Commentors=13.4%

Not Specified=3.4% (N=4)

Findings

Several themes emerged from the participants’ accounts of sexism. The most prevalent themes include the following: (1) Gender Stereotypes, (2) Women’s Role as Homemakers, (3) Undervaluing Women’s Contributions, (4) Infantilizing/Condescending, and (5) Sexualization/Objectification. Many responses also pointed to (6) a Misunderstanding (by the offender) of the Role of the Priesthood, which is also important to explore. Please note that many of these comments were included in more than one category, as a single comment can be related to several different sexist themes.

Theme 1: Gender Stereotypes

Forty-two (35.3%) of the comments reported by study participants reflected common gender stereotypes. Respondents gave examples of phrases they had heard directed toward women, including, “Women are the guardians of virtue,” “Sisters . . . are just too emotional,” and, as mentioned previously, “Women are suited for nurses, teachers and motherhood. Let’s not distract from where God-given talents reside.” One woman shared a story of a council wherein the women in attendance were largely ignored and then given all the responsibilities for a large multi-stake activity. When she asked if the men could help with the event she was told, “Women are just so much better at these things.” Comments describing stereotypes about men were also included, such as, “Fathers are the rulers in the home,” and that a job promotion “should go to a man because men think more clearly.” Though a large majority of the comments coded as gender stereotypes were also related to marriage and motherhood (as demonstrated in the next section), the variety of comments related to this theme show that stereotypes of all kinds are commonly held (and commented on) by Church members in this region.

Theme 2: Women’s Role as Homemakers

Of the 42 remarks perpetuating gender stereotypes, 31 (or 26.1% of the total comments) were specifically about the need for women to prioritize homemaker roles (primarily marriage and motherhood). A single, female law student in the study recalled being asked, “What will your future husband think about [her attending law school]?” As a new convert and an active-duty member of the United States Army at the time, another woman heard a talk by a member of the General Relief Society Presidency, in which it was stated that “it is inappropriate for women to serve in the military, as their highest ideals won’t be developed there. That we women should prepare for motherhood and learn to best use the resources that our husbands bring home for the family.” A Stake President told a group of Relief Society sisters that “too many girls and not enough men were going on missions after the age change. He said that as mothers it was our job to make sure our daughters understood that marriage was more important, and our sons understood that missions are a priesthood requirement.” Women were told, “Your priority is to get married,” and one respondent noted that women were often referred to “only via reference to their relationship status— ‘married women, single women, mothers… .’” The priority for women to get married and become mothers was a prevalent theme throughout the study. Of course, marriage and motherhood are doctrinally foundational roles for women, but they are not women’s only roles, and further, attaining these roles is often outside of a woman’s control. Frequent comments of this type made many women in the study feel diminished (especially if they were not wives and mothers) and further dismissed in terms of their other qualities and contributions.

Theme 3: Infantilizing/Condescending

Comments that were infantilizing or condescending in nature showed up in 33 (27.7%) responses. One woman stated, “Any time I am asked to do something at church (a calling) the bishopric wants my husband present. I was told it was because callings are a ‘decision to be made between spouses.’ But when my husband gets a calling, I am never invited to join.” Another woman shared that, when she brought some questions and concerns to a religious leader, he immediately responded, “I know you think you have these concerns, but you don’t. What you are lacking is faith. Women often lack faith to see the truths in this area.” A female college professor who had taught for over 20 years in Utah responded that “a specific demographic of students tends to exercise microaggressions towards me. Specifically, white, LDS male students who are returned missionaries and unmarried. They make snide comments in the classroom to each other in what I call ‘back of the bus’ attitudes.” Whether it was due to an assumed lack of authority or women’s supposed “lesser” status in church settings, comments under this theme showed condescension toward or bias against women in a variety of ways.

Theme 4: Undervaluing Women’s Contributions

On a similar note, 24 respondents (20.2%) shared experiences that undervalued women’s contributions. When one respondent’s family couldn’t agree on a decision, she reports her then-husband stating, “You don’t have a vision like I do, so you can’t make that decision…You need to accept my role as patriarch in making the final decision.” During a stake Young Women meeting, a member of one of the bishoprics was asked to speak to about 150 teen girls ages 12-18. The survey participant stated, “He meant well and wanted to say they were special and had great potential and all of that. But what he ended up using as his example was the way that boys always play basketball better when girls are watching them. His message [to these girls] was that their greatest strength was their ability to make men better at whatever they were doing.” Although the biases demonstrated here are likely unconscious and presumably not malicious, comments like these undermine the ability for women to feel as if they are valuable, contributing, and equal members of their congregations or even their families.

Theme 5: Sexualization/Objectification

Nineteen respondents (16.0%) shared experiences in which the focus was placed on women’s bodies, often as sexual objects. Many of these comments focused on the need for women and girls to dress modestly. One participant was told during a temple recommend interview that “Garments and modesty are more important for women.” In a presentation to young women, a speaker stated, “Sometimes, if you wear clothes that are too revealing, [men] might assault you and lose control of themselves. Modesty is a protection.” These comments put both the responsibility and blame on women for the thoughts and actions of men. Ironically, in a supposed effort to promote chastity, comments like this actually contribute to the sexualization of women.

Aside from modesty, women recounted other forms of objectification. One woman shared, “Our bishop said (over the pulpit) that his pretty wife was a reward for him being a good missionary, so the young men in the ward needed to be good missionaries.” Another respondent shared that, after the girls she taught in Primary were sad they couldn’t participate in a father/son campout, she asked the bishop of the ward if they could do a family campout instead. Her bishop responded that “women’s bodies are too demanding. If they allowed women and girls to come, the ward would have to find camping facilities with toilets, which would cost more and be a hassle.” Overall, comments in the sexualization/objectification theme revealed a larger tendency for women to be viewed or treated more as objects than human beings.

Theme 6: Priesthood

According to the Church Handbook (July 2021 Update), [13] “Church leaders and members use conferred or delegated priesthood authority to bless the lives of others. This authority can be used only in righteousness… Those who exercise priesthood authority do not force their will on others. They do not use it for selfish purposes.” Despite this clear direction, 10 comments (about 8.4% of the responses) showed priesthood authority being used to convey gender inequity. One respondent shared that, while serving as a sister missionary, multiple Zone Leaders “would tell us that we couldn’t train because we were women, we couldn’t receive revelation because we were women, and we didn’t have authority because we were women.” Another participant shared, “I grew up in the Church all over the country, but since moving to Utah I get a lot [of my ideas for ward activities] shut down based on priesthood authority. When I ask why I have to make a change to my activities, I get told that men have the priesthood, and we should accept their decisions.” Women in the study expressed frustration that priesthood authority was used as justification by men in order to diminish or demean women.

Overall, in examining the sexist comments made in religious contexts, it is interesting to note that while some comments were clearly hostile, many of them likely seemed harmless or even appropriate to the speaker. Comments related to stereotypes, women’s roles, or priesthood authority could feel justified based on commonly held doctrinal or cultural beliefs. And condescending or objectifying statements could be the result of false or misdirected efforts to protect women. Yet regardless of the commenter’s intentions, the sexist statements reported in this study made women feel frustrated, misunderstood, lesser-than, and even ostracized in their congregations and relationships.

For readers who would like to read the Utah research and policy briefs released on this study, which includes the data that reports on how women responded to the comments, see the following:

- Sexist Comments & Responses: Study Introduction and Overview

- Sexist Comments & Responses: Inequity and Bias

- Sexist Comments & Responses: Objectification

- Sexist Comments & Responses: Stereotypes

- Sexist Comments & Responses: Undervaluing Women

Conclusion

The goal of this study was to educate readers on the various ways that language and related behaviors can demean and disempower women, particularly as Church members interact with each other in various contexts. By raising awareness of the widespread occurrence and damaging effects of sexist language, comments, beliefs, and behaviors, we can reduce the frequency of sexism in the Church and in our interactions with others. Sexism is not doctrinally supported within the Gospel of Jesus Christ, yet sexist comments and behaviors are common in many of our congregations. There is clearly a need to identify, discuss, and root out these damaging practices that harm Church members and generally prevent us from becoming a united community in Zion. As the late prophet Gordon B. Hinckley expressed, “You sisters … do not hold a second place in our Father’s plan for the eternal happiness and well-being of His children. You are an absolutely essential part of that plan.” [14] The way this sentiment is enacted by members of the Church should be in the forefront of our minds as we seek to eliminate sexism in our homes, congregations, and in the Church as a whole.

We invite readers to offer their own experiences in the comments app below, as well as how they have effectively dealt with sexist comments in the Church.

NOTES:

[1] Simon, S., & O’Brien, L. T. (2015). Confronting sexism: Exploring the effects of nonsexist credentials on the costs of target confrontations. Sex Roles, 73(5-6), 245-257. http://doi.org/10.1007/n11199-015-0513-x --- [Back to manuscript].

[2] See https://www.usu.edu/uwlp/research/briefs for five “Sexist Comments & Responses” briefs: No. 38, 39, 40, 42, and 43. [Back to manuscript].

[3] Ballard, M. R. (2013, April). “This is my work and glory.” General Conference. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2013/04/this-is-my-work-and-glory?lang=eng (p. 19). [Back to manuscript].

[4] Ballard, M. R. (2012). Counseling with our councils, revised edition: Learning to minister together in the Church and in the family. Deseret Book (p. 203).

[Back to manuscript].

[5] Nelson, R. M. (2015, October). “A plea to my sisters.” General Conference. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2015/10/a-plea-to-my-sisters?lang=eng (p. 97). [Back to manuscript].

[6] McBaine, N. (2014). Women at Church: Magnifying LDS Women’s Local Impact. Greg Kofford Books (p. xviii). [Back to manuscript].

[7] Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Sexism. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sexism --- [Back to manuscript].

[8] Gul, P. & Kupfer, T. R. (2018, June 29). Benevolent sexism and mate preferences: Why do women prefer benevolent men despite recognizing that they can be undermining? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218781000 --- [Back to manuscript].

[9] Madsen, S. R. (2021, July 23). Understanding ‘benevolent sexism’ can help us be better Utahns. The Salt Lake Tribune. https://www.sltrib.com/opinion/commentary/2021/07/23/susan-madsen/

--- [Back to manuscript].

[10] Ibid. [Back to manuscript].

[11] Utah Women & Leadership Project. (n.d.). Website. www.utwomen.org

--- [Back to manuscript].

[12] reference [Back to manuscript].

[13] 3.4.4 Exercising Priesthood Authority Righteously. General Handbook: Serving in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. https://abn.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/general-handbook/3-priesthood-principles --- [Back to manuscript].

[14] Hinckley, G. B. (1996, October). “Women of the Church.” General Conference. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/1996/10/women-of-the-church?lang=eng (p. 68). [Back to manuscript].

![]()

Full Citation for this Article: Susan R. Madsen, Robbyn T. Scribner, & Allie Barnes (2022) "Sexist Comments in Latter-day Saint Settings," SquareTwo, Vol. 15 No. 1 (Spring 2022), http://squaretwo.org/Sq2ArticleMadsenScribnerBarnesSexism.html, accessed <give access date>.

![]() Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome.

Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome.