The Utah Women & Leadership Project has a series of Utah Women Stats research snapshots with the goal of providing specific, timely data on a series of issues relevant to Utah women. In November of 2017, we released a snapshot titled Utah Women and Mental Health. The following article has been adapted from this report and we, as authors, hope it is useful for those interested in learning more about the status of women in Utah—both LDS and non-LDS. While Mormon women in Utah are not singled out specifically throughout in these reports (they are mentioned), we believe that the data here are valuable to the SquareTwo audience as they give a sense of what Utah women (many of whom are LDS) are facing in terms of these serious issues. The original snapshots, along with other briefs and snapshots can be found on the Project’s website: www.utwomen.org.

Setting the Stage

According to the World Health Organization, “There is no health without mental health.”[1] A national report stated that in 2015 nearly 1 in 5 adults in the U.S. (43.4 million, or 17.9%) suffered from a mental illness and that 9.8 million Americans (4% of all adults) had a serious mental illness.[2] Although one recent in-depth study showed Utah ranking slightly below the national average in the percentage of adults who suffer from poor mental health, the state regularly reports rates higher than the national average for depression.[3] Another recent study that considered both the percentage of adults with mental illness and their access to affordable care (among other factors) ranked Utah last out of all 50 states plus D.C.[4] Utah women, like women nationally, are diagnosed with depression at much higher rates than men.[5] Understanding the factors surrounding mental illness and increasing access to successful treatment and support will improve the overall well-being of women in Utah.

This research snapshot focuses on three key areas:

- An overview of mental health rates for women, including key demographics;

- An analysis of factors surrounding mental health conditions in Utah; and

- A discussion of current efforts being made in the state to improve mental health among women.

Mental Health by the Numbers

The Utah Department of Health states that “mental health refers to an individual’s ability to negotiate the daily challenges and social interactions of life without experiencing undue emotional or behavioral incapacity.”[6] Mental conditions can be influenced by genetic factors, chronic physical infirmities, and environmental stressors.[7] Although there are a host of mental health conditions, depression and anxiety disorders are among the most common and are the main focus of this report.

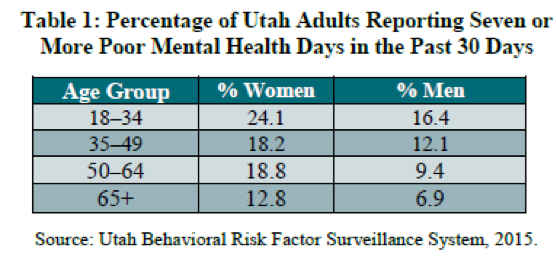

Poor mental health is a concern for people of all ages and can vary by gender, race, and ethnicity. In terms of gender, the 2016 Utah State Health Assessment reported that Utah women suffered from poor mental health at much higher rates than men (19.8% vs. 12.1%). [8] A common method of gauging mental health is through surveys asking respondents to self-assess. Utah women report having an average of 4.2 days per month of poor mental health, a higher monthly average than that reported by Utah men (2.7 days). [9] Additionally, the percentage of Utah women reporting more than seven days of poor mental health over the prior 30 days is higher than men at every age, with nearly a quarter of all women ages 18–34 falling into this group. [10] This may be due in part to mental health conditions that are more common among women during childbearing years.

Some mental health conditions are specific to women, such as perinatal mood disorders occurring both during and after pregnancy. One condition, postpartum major depression, is reported to be the “most common complication of childbirth and the most common perinatal psychiatric disorder.” [11] The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that 15% of postpartum women experience depression, a serious condition that differs from the widespread “baby blues.” [12] A 2009 research study of Utah women found that postpartum depression symptoms were more common (14.7%) than gestational diabetes (2.4%), pregnancy-associated hypertension (5.5%), and preterm birth (10.0%), among women in their childbearing years; however, postpartum depression is less frequently diagnosed and treated and is less often the subject of obstetric research. The study showed that approximately 60% of women who experienced symptoms of postpartum depression did not seek help from a medical professional; [13] this may be particularly relevant to women who receive health benefits under Medicaid, which provides coverage for mothers for only 60 days following a child’s birth. [14] More recent data show that 15.3% of Utah women reported frequent postpartum symptoms, which is higher than the national average of 10.1%. Utah was second highest of 26 reporting sites in that study. [15] As Utah has the highest birthrate in the nation [16] and the largest household size [17] (which adds pressure for new mothers), efforts to understand and treat postpartum depression are greatly needed.

Mental health diagnosis and treatment can also vary according to race or ethnicity, although reports tracking these factors often differ based on the specific factors being captured. A recent U.S. study showed that the adults most likely to utilize mental health services were those who reported belonging to two races (17.1%), followed by those who identified as White (16.6%), American Indian or Native Alaskan (15.6%), Black (8.6%), Hispanic (7.3%), and Asian (3.1%). [18] However, these numbers do not necessarily represent the actual percentages of people who have mental health concerns. Research shows that, despite having similar rates of mental health disorders as those of other Americans, racial or ethnic minorities are less likely to use mental health services for various reasons (e.g., cost, access to health insurance, and cultural attitudes), and they are more likely to receive sub-par care when they do utilize these services. [19]

The 2016 Utah State Health Assessment found that those who identified as American Indian or Native Alaskan were the most likely to report suffering from poor mental health (21.3%), followed by Pacific Islander (17.3%), White (16.0%), Asian (15.6%), and Black (15.1%). Non-Hispanic adults were more likely to report experiencing poor mental health (16.1%) than Hispanic adults (14.6%) (of all races). [20] There were no readily available state or national data regarding racial/ethnic percentages by gender; more information on this intersection is needed.

Factors Surrounding Mental Health Conditions

Mental health disorders can be connected to or exacerbated by many factors, including poverty, lower education levels, poor physical health, and negative life experiences. A recent national study showed that those living below the poverty line were more than twice as likely to have depression as those living at or above the poverty level (15% vs. 6.2%). [21] In Utah, the mental health indicators for women living in poverty are also substantial. In 2016, 36.9% of Utah women living at or below the federal poverty level reported having seven or more poor mental health days in the last 30 days versus only 18.5% of women living above the poverty level. [22] Lower levels of education also correlate with poor mental health. In 2016, 29.1% of Utah women with no high school degree reported having seven or more poor mental health days in the last 30 days versus 22.2% of women with a high school degree, 23.0% of women with some college, and 13.9% of women with a college degree. [23]

Mental health conditions are often compounded by significant physical health problems. Healthy People 2020 states that mental health disorders are “associated with the prevalence, progression, and outcome of some of today’s most detrimental chronic diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.” [24] While it can be difficult to determine which comes first, the mental health concern or the chronic health issue, people in Utah who have one severe chronic disease are more likely to take antidepressants (15.6%) than the average Utahn (12.7%). For those who suffer from two significant chronic disorders, the use of antidepressants jumps to 43.2%. [25] These results indicate the need to consider both physical and mental health when addressing the overall well-being of women.

Negative life experiences are also related to poor mental health. Utah adults who faced adverse life events as children showed higher than average levels of current depression. These detrimental experiences varied from familial issues such as divorce, domestic abuse, or violence, to household substance abuse or having an incarcerated household member. Such experiences raised the rates of current depression from slightly above average to more than three times the average levels. [26] A separate study showed that one-third to one-half of Utahns suffering from a severe mental illness had experienced childhood physical or sexual abuse. [27] This is particularly relevant for Utah women as our state reports higher levels of both domestic abuse and sexual assault than the national average (see previous research snapshots for more details). [28]

Just as many factors seem to contribute to poor mental health, these disorders themselves can have serious negative impacts on all areas of a person’s life. For example, those with untreated mental health disorders are at high risk for dangerous behaviors, such as substance abuse, violence, or suicide. [29] Sadly, Utah ranks seventh in the nation for suicide deaths, [30] and suicide is the leading cause of death among Utahns aged 10–17. [31] In the U.S. and most other countries, men have a higher rate of death by suicide although women attempt at a higher rate. [32] Utah women have a rate of death by suicide that is significantly lower than men in the state and nation, but higher than the rate of U.S. women: in 2015 the rate of suicides per 100,000 population was 12.1 for Utah women versus 7.1 for U.S. women. [33] According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from 2012–2014 Utah had the fourth-highest female suicide rate (all ages) among 50 states and D.C. Utah’s national ranking of suicides among adolescent females is also startling. From 2012–2014, Utah females aged 10–19 had the highest suicide rate among the 31 states reporting usable data. [34]

Efforts to Address Mental Health in Utah

Many tools can be utilized to treat mental health conditions, including medication. Antidepressants are in widespread use for depression and related disorders, and these medications are among the top three therapeutic drugs prescribed in the U.S. Nationally, across all age groups, women are about twice as likely to use antidepressants as men. [35] A frequently cited survey by Express Scripts (published in 2002) found that Utah had the highest rate of antidepressant use in the country—at a rate that was around twice the national average. [36] Although more current state-by-state rankings are lacking, recent studies show Utah women’s use of antidepressants in 2009 was a few percentage points lower [37] than the national average for women in 2010. [38] Because these studies used different methodologies, a direct comparison of their findings is not possible, and up-to-date research of antidepressant use by state is needed. The same 2009 Utah review of commercial health insurance claims showed that 68% of patients who were prescribed antidepressants were women, and these drugs were top of the list for dollars spent on medications for women (about 10% of total expenditure). [39] While antidepressants are a common treatment, experts caution against their overuse, especially when they are prescribed to treat depression in young people. [40]

Individual or group therapy is another tool that is frequently used to address mental health issues, yet only 45% of adults and 41% of adolescents in Utah with mental health conditions receive treatment. [41] In addition, the number of mental health professionals per capita in Utah is well below the national average, and each county in the state has been designated a Mental Health Provider Shortage Area. [42]

Of course, affordable access to treatment is key to the successful management of mental health issues, regardless of the therapies prescribed. In 2016, approximately 94,000 Utah women between the ages of 18 and 64 lacked health insurance (10.5%, which is close to the national average). Additionally, research shows that in Utah, as in much of the U.S., insurance coverage varies widely among ethnic groups. A 2014 report showed that non-Hispanic minority women and Hispanic women were much more likely to be without health insurance than non-Hispanic white women in Utah. [43] Without access to affordable health care, women are less likely to be diagnosed or treated for mental health issues. Increased access to health insurance coverage that includes mental health benefits is a crucial need in promoting Utah women’s mental health.

Finally, efforts to increase awareness of mental health disorders and to reduce the stigma surrounding these conditions are crucial. Several organizations are working to promote mental health awareness and well-being in Utah. The Utah Department of Human Services Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health is the state agency responsible for ensuring that mental health services are available statewide. This agency also provides general information, research, and statistics to educate the public about mental health and substance abuse issues. Another group, the non-profit National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), is the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization dedicated to building better lives for those affected by mental illness. These and other stakeholders must continue to reduce the stigma and raise overall awareness of mental health concerns, particularly among those who are most vulnerable and least likely to know how to access help when they need it.

Conclusion

Good mental health is essential for personal well-being, successful relationships, and the potential to live a productive life. [44] As mentioned previously, while Mormon women in Utah are not singled out often in these reports, we do believe that the data here are valuable in providing a sense of what Utah women (many of whom are LDS) are facing in terms of the serious issues that thwart women’s physical, emotional, mental, financial, and spiritual wellbeing. And, of course, all of these are directly or indirectly related to women’s struggle with finding their own confidence and voices, as well as their path toward greater influence and leadership.

In Utah and throughout the nation, women report having mental health issues at a higher rate than men. A wide variety of factors can influence each person’s overall mental health, and when serious mental disorders remain untreated, there can be severe, even tragic, consequences. Individuals, families, health professionals, organizations, and policy makers must continue their efforts to reduce stressors or other known factors that negatively influence mental health when possible and more fully diagnose and successfully treat mental health disorders as they arise. Doing so will strengthen the positive impact of women in their families, their communities, and in the state as a whole and beyond.

NOTES:

[1] World Health Organization. (2016, April). Mental health: Strengthening our response. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs220/en/ --- [Back to manuscript].

[2] Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). Key substance abuse and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 national survey on drug use and health. HHS Publication No. SMA 16-4984, NSDUH Series H-51. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015.htm --- [Back to manuscript].

[3] Utah Department of Health Office of Public Health Assessment. (2016). Utah state health assessment 2016. Retrieved from https://ibis.health.utah.gov/pdf/opha/publication/SHAReport2016.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[4] Mental Health America. (2016). The state of mental health in America 2016. Retrieved from http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/sites/default/files/2016%20MH%20in%20America%20FINAL.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[5] Utah Department of Health. (2016, December 15). Complete health indicator report of depression: Adult prevalence. Public Health Indicator Based Information System (IBIS). Retrieved from https://ibis.health.utah.gov/indicator/complete_profile/Dep.html --- [Back to manuscript].

[6] Utah Department of Health. (2017, May 26). Complete health indicator report of health status: Mental health past 30 days. Public Health Indicator Based Information System (IBIS). Retrieved from https://ibis.health.utah.gov/indicator/complete_profile/HlthStatMent.html --- [Back to manuscript].

[7] Utah Department of Health. (2017, May 26). [Back to manuscript].

[8] Utah Department of Health Office of Public Health Assessment. (2016). [Back to manuscript].

[9] Hess, C., & Williams, C. (2014, May). The well-being of women in Utah. IWPR #R379. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Retrieved from https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/wpallimport/files/iwpr-export/publications/R379.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[10] Utah Department of Health. (2017). Mental health past in the past 30 days by sex and age group, 2015 data. Public Health Indicator Based Information System (IBIS). Retrieved from https://ibis.health.utah.gov/indicator/view/HlthStatMent.Sex_Age.html --- [Back to manuscript].

[11] Moses-Kolko, E. L., & Roth, E. K. (2004, Summer). Antepartum and postpartum depression: Healthy mom, healthy baby. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, 59(3), 181–91, p. 182. [Back to manuscript].

[12] National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.) Postpartum depression facts. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/postpartum-depression-facts/index.shtml --- [Back to manuscript].

[13] McGarry, J., Kim, H., Sheng, X., Egger, M., & Baksh, L. (2009). Postpartum depression and help-seeking behavior. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 54(1), 50–56. [Back to manuscript].

[14] Utah Department of Health: Medicaid. (n.d.). Pregnant woman. Retrieved from https://medicaid.utah.gov/pregnant-woman --- [Back to manuscript].

[15] Utah Department of Health. (2016, October 13). Complete health indicator report of postpartum depression. Public Health Indicator Based Information System (IBIS). Retrieved from https://ibis.health.utah.gov/indicator/complete_profile/PPD.html --- [Back to manuscript].

[16] Utah Department of Health. (2017, March 15). Complete health indicator report of birth rates. Public Health Indicator Based Information System (IBIS). Retrieved from https://ibis.health.utah.gov/indicator/complete_profile/BrthRat.html --- [Back to manuscript].

[17] United States Census Bureau. (2010). Profile of general population and housing characteristics. DP-1. [Back to manuscript].

[18] National Institute of Mental Health. (2015, April 23). A new look at racial/ethnic differences in mental health service use among adults. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2015/a-new-look-at-racial-ethnic-differences-in-mental-health-service-use-among-adults.shtml --- [Back to manuscript].

[19] Office of the Surgeon General. (2001). Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity. Chapter 1. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44243/ --- [Back to manuscript].

[20] Utah Department of Health Office of Public Health Assessment. (2016). [Back to manuscript].

[21] Pratt, L. A., & Brody, D. J. (2014, December). Depression in the U.S. household population, 2009–2012. NCHS Data Brief no. 172. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db172.htm --- [Back to manuscript].

[22] Utah Department of Health. (2017, May 26). Query by income level. [Back to manuscript].

[23] Utah Department of Health. (2017, May 26). Query by education level. [Back to manuscript].

[24] Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Healthy people 2020: Mental health. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-lhi-topics/Mental-Health --- [Back to manuscript].

[25] Utah Department of Health. (2010). Antidepressant use in Utah. Utah Atlas of Healthcare, 1(1). Retrieved from http://digitallibrary.utah.gov/awweb/awarchive?type=file&item=37047 --- [Back to manuscript].

[26] Utah Department of Health. (2014, October). Utah health status update: Major depression. Retrieved from https://ibis.health.utah.gov/pdf/opha/publication/hsu/2014/1410_Depression.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[27] Utah Department of Human Services. (2016). Division of substance abuse and mental health annual report. Retrieved from https://dsamh.utah.gov/pdf/Annual%20Reports/2016%20Annual%20Report%20Web%20Final.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[28] See Madsen, S. R., Turley, T., & Scribner, R. T. (2017). Domestic violence among Utah women. Utah Women & Leadership Project. Retrieved from https://www.uvu.edu/uwlp/docs/uws_domestic-violence.pdf and Madsen, S. R., Turley, T., & Scribner, R. T. (2016). Sexual assault among Utah Women. Utah Women & Leadership Project. Retrieved from https://www.uvu.edu/uwlp/docs/uws_sexualassault.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[29] Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). [Back to manuscript].

[30] Utah Department of Human Services. (2016). [Back to manuscript].

[31] Utah Department of Health. (2017, March 13). Complete health indicator report of suicide. Public Health Indicator Based Information System (IBIS). Retrieved from https://ibis.health.utah.gov/indicator/complete_profile/SuicDth.html --- [Back to manuscript].

[32] Freeman, D., & Freeman, J. (2015, January 21). Why are men more likely than women to take their own lives? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/jan/21/suicide-gender-men-women-mental-health-nick-clegg --- [Back to manuscript].

[33] Utah Department of Health. (2017, March 13). [Back to manuscript].

[34] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Fatal injury mapping. Query by suicide, 2012–2014, females only, all ages, and ages 10–14 and 15–19. WISQUARS. Retrieved from https://wisqars.cdc.gov:8443/cdcMapFramework/mapModuleInterface.jsp --- [Back to manuscript].

[35] Pratt, L. A., Brody, D. J., & Gu, Q. (2017, August). Antidepressant use among persons aged 12 and over: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief no. 238. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db283.htm --- [Back to manuscript].

[36] Cart, J. (2002, February 20). Study find Utah leads nation in antidepressant use. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/2002/feb/20/news/mn-28924 --- [Back to manuscript].

[37] Utah Department of Health. (2010). [Back to manuscript].

[38] Medco. (2011). America’s state of mind. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19032en/s19032en.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[39] Utah Department of Health. (2010). [Back to manuscript].

[40] Utah Department of Health. (2004). Utah pharmacy data plan: Version 1. Retrieved from http://stats.health.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/UtahPharmacyDataPlan.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[41] Christensen, J. (2016). Utah’s mental health workforce, 2016: A study on the supply and distribution of clinical mental health counselors, social workers, marriage and family therapists, and psychologists in Utah. The Utah Medical Education Council. Retrieved from https://www.utahmec.org/wp-content/uploads/Mental-Health-Workforce-2016-1.pdf --- [Back to manuscript].

[42] Christensen, J. (2016). [Back to manuscript].

[43] Hess, C., & Williams, C. (2014, May). [Back to manuscript].

[44] Healthy People 2020. (n.d.) Leading health indicator topics: Mental health. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-lhi-topics/Mental-Health --- [Back to manuscript].

![]()

Full Citation for this Article: Robbyn T. Scribner, Susan R. Madsen, & Elyse Barnes (2018) "Utah Women and Mental Health," SquareTwo, Vol. 11 No. 2 (Summer 2018), http://squaretwo.org/Sq2ArticleMadsenMentalHealth.html, accessed <give access date>.

![]() Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome. Please submit to SquareTwo.

Would you like to comment on this article? Thoughtful, faithful comments of at least 100 words are welcome. Please submit to SquareTwo.